Rich Rodriguez would not stand to benefit from it, but Michigan’s next All-American defensive back roamed the sidelines before practice one warm day in 2009, surveyed what was (and was not) happening on the field, and from that moment, in Rodriguez’s parlance, was ‘all in.’ Jourdan Lewis stood on the field behind the shiny new Glick Field House that day and saw Denard Robinson—“Nardy,” as Lewis calls him— scampering, pulling, darting around and away from defenders— and no one else he recognized. Compared to 2006, a team full of names like Breaston and Henne and Hart and Manningham, names that Lewis reels off with ease, the only thing similar was that the players in front of him were clad in the familiar winged helmet. Lewis wanted then precisely what he wants now: to be a football star, and to use the platform afforded a football player to change the culture.

[After THE JUMP: “…he knows what lifelines can do, because he was given it.”]

********

Home, as they say, is largely what you make of it. Lewis lived in Detroit for the first three years of his life before his family moved to Roseville, where they resided until he was in seventh grade. Still, daily trips to Lewis’s grandmother’s house in Detroit kept his ties to the city strong. Those trips to grandma’s house became formative experiences in a number of ways, not the least of which was the kind of teasing only family members can execute, the kind where someone knows you so well they can perfectly tailor their jabs to most effectively get under your skin. By the time Lewis was finishing elementary school, his cousins’ lampooning Roseville’s level of little league football competition started to sink in. “My cousins, they really grew up in Detroit PAL [Police Athletic League] and stuff like that,” Lewis says. “I didn’t get into PAL until I was 12, 13, so when I got there my cousins were always bothering me, saying oh, I’m in a terrible league and stuff like that; ‘Yeah, you score all these touchdowns but you ain’t playing nobody’ and stuff like that.”

Tired of being teased and eager to prove himself against better competition, Lewis asked his mother if he could play PAL football. His mother agreed and helped find the best possible team for Lewis: the Westside Cubs, a Detroit institution that counts Willie Horton, Ron Johnson (both of them), Thomas Wilcher, Marion Barber Jr., Larry Foote, Braylon Edwards, Devin Funchess, Edwin Baker, James Ross, Terry Richardson, Royce Jenkins-Stone, Desmond King, and Malik McDowell among their alums. Even Gus Johnson, the Fox sportscaster loved by fans and loathed by audio engineers, was once a Westside Cub.

The track record of producing college football players was clearly there, but as his first PAL season wore on it didn’t look like Lewis would be included on that list. Lewis’s cousins had a point, and the increased level of competition led to Lewis doing more watching than playing his first year in the organization. “I sat the bench behind Terry Richardson,” Lewis says. “Terry was a PAL legend. Back then I was like, man, how do I get on the field? I’m frustrated. I’ve never been through this and stuff like that.”

Lewis did eventually see the field, but it was something of a double hit to his confidence: not only was he playing wingback, a position similar to a spread H-back that he describes as the lowest back in the offense’s pecking order, but he was the last player rotating in at the position. Adding insult to injury, or in this case because of it, Lewis also lost his nickname partway through the season. “Once you get the nickname everybody starts calling you by your nickname and everybody knows who this is. They want to go see them play and stuff like that. It took me a while,” Lewis says. “First, it was Spin City. That was my first nickname. I was Spin City because I used to spin a lot. Then I got hit real hard and stopped spinning. [Coach Rock] was just like, man, we got to get you a nickname. JL, that don’t rhyme. JJ, that’s common. And he was like ‘JD’ and I’m like ‘Alright, whatever.’ It just came out of nowhere. Really no meaning.”

Like any song on pop radio, the meaning was less important than catchiness, and people hearing and recognizing the name supersedes its origin relatively quickly; the latter took longer for Lewis to achieve than he would have liked. “I’m seeing people play that I know that I can play over and just seeing everybody getting praise and I’m just like, man…nobody knowing my name, really, because we had nicknames,” Lewis says. “Like, PAL was a big thing in Detroit back then. It was almost as big as a high school back then. You had the reputation. Desmond [King], his nickname was Buddha. Everybody knew him. It was crazy. I’m just like, man, I can play with these guys.”

Lewis credits his season-long frustration for creating the work ethic that he has to this day; he says that the totality of his thoughts from the end of his first PAL season to the beginning of his second season was that he will play in year two; the intonation and cadence with which he says this reads as absolute conviction. Outside, he started running to increase his speed and joined his middle school’s track team. Inside, he was playing NCAA Football ‘06 on the XBox in his room, always playing Race for the Heisman mode. He quickly became obsessed with the Heisman, convincing himself that he would someday win the trophy. Lewis was physically catching up to his peers thanks to his training, and he now had the desire not just to be good—that, he says, kicked in around age 9—but to be the best; “I always wanted to win the Heisman. I always wanted to be the best collegiate player that has ever played,” Lewis says as he reflects on what the video game meant to him. “When I was younger I always used to draw and stuff like that and [drew] ‘Heisman 2013,’ not knowing that that was my freshman year, just knowing that when I get to college I’m going to win the Heisman.”

Two elements were in place, but there was still something missing. Between his seventh and eighth grade years, Lewis’s family moved to Detroit. He would be transferring from Roseville Middle School to University Preparatory Academy, near Midtown. Now he would not only be seeing his teammates at practice a few times a week but would be spending all day with many of them in school; his teammates were now his peers. The competitive fire stoked by his cousins was doused with lighter fluid by Lewis’s classmates at University Preparatory Academy. “A lot of those guys were real confident,” Lewis says. “They were just [saying], ‘I can do this’ or ‘I can do that’ and it’s like, man, you know what I’m saying? I’ve got to get that to me, and then that’s when I really started getting that grit to me and it was amazing, just the mindset I had after year one.”

Lewis’s second PAL season got off to an inauspicious start, as he once again stood on the sidelines and watched his teammates make names for themselves—for one half, at least. “My first game, I remember this guy, we called him LA, his name was Allen,” Lewis says. “So, he was starting at the wingback position that year before that I wasn’t playing a lot. He started at running back the next year, and first year [at the position], first game we were struggling and then I got put in the second half and my first run, I go for like 70 yards. Ever since then I took over that spot, and it’s just crazy how that one game just boosted my confidence. Never looked back.”

Terry Richardson shared the field with Lewis that season and every season after that through 2015. One year older than Lewis, Richardson experienced a similar year-two jump as Lewis, but his took place the season that Lewis spent watching from the bench. Lewis credits Richardson as having played a big role in his football career, as he saw Richardson ripping off multiple touchdowns with ease every game and wanted to get in on the glory. Richardson remembers Lewis as an incredibly talented player who didn’t even realize he had talent in his first PAL season. “You could just tell that his talent took off,” Richardson says about Lewis’s second season with the Cubs. “He just started being the guy that everybody thought he could be. He found his comfort zone out there, and from that next year up until today, Jourdan’s still that same player who just, every time he plays, you never know what to expect, but expect something great."

Lewis went on to dabble at receiver a bit as well as starting at running back, and he quickly drew praise from his coaches. William Tandy, the head coach of the Cubs’ A team, says he quickly realized that Lewis had skills that could not be taught. “He was our slot guy and defensive back and could catch a BB in the dark,” Tandy says. “He could catch a BB in the dark. The kid would make Barry Sanders-type plays every Saturday. Every Saturday.”

Tandy is reluctant to credit himself as the reason Lewis is a Division I cornerback, but he admits that he likes to nudge his offensive stars to consider playing two ways. “The reason being is that most defensive backs are receivers that can’t catch,” Tandy says. “Those defensive backs that are receivers that can catch become special.” Tandy adds that it also comes down to logic: “I just believe that there are always going to be four to five defensive backs on the field. You’re going to get sometimes two or three receivers on the field, sometimes four. And so for me it was simplistically the concept of your best chance of getting a scholarship, because you’re going to take more defensive backs than you are receivers.”

The laundry list of star Westside Cubs alums should paint a picture of the kind of talent that typically is part of the organization, and that talent manifests in more than just on-field ability. Tandy tries to cultivate his players’ academic interests in every possible way; when discussing the organization’s motto—God, books, and ball—he notes that the first two have to come before the third. He loves taking his players to visit different colleges, showing them not only the football facilities but things he thinks might interest them on campus.

Lewis grew up a Michigan fan and followed the first two parts of Tandy’s team motto in earnest, and as a result was part of a group that made a trip to U-M to spend the day on campus and take in a practice. Chris Singletary, a member of Michigan’s 1997 title team and the program’s recruiting coordinator at the time, is a Cubs alum, and as such was happy to help show Tandy’s players around. Tandy asked Singletary if he and some of the Michigan players would talk to the Cubs, with one very specific edict: tell them that they can make it at Michigan.

“I knew that if I can get him up there and he can see the starting defensive backs that were just a little bit taller and a little bit wider and he’s an eight grader or ninth grader, that he can see himself there,” Tandy says. “So, part of the process for the Cubs is to make a young man visualize, to see himself in a certain place.”

The trip made an indelible impression on both Lewis and Richardson, who was also a part of Tandy’s tour group that day. Both mention how it was their first real taste of both college and college football, and they recount the day with the kind of enthusiasm of someone on the precipice of their athletic awakening, that all-important moment at the dusky end of childhood where sports become life and something like getting a pair of gloves from an honest-to-god college football player (which both were given) is the kind of tangible motivation that even the best bulletin board material fails to provide. Tandy doesn’t recall Lewis explicitly stating that he was a Michigan fan, but he always knew where Lewis stood. “I have Cubs at Michigan State and Cubs at Michigan,” Tandy says. “I never took Jourdan to Michigan State.”

An extra bit of motivation for Lewis to eventually choose Michigan came from what he didn’t see on the field at that practice, which was players he recognized. The dissonance between the 2006 team and the 2009 team struck him, and he decided that day that he wanted to be a part of a change at Michigan, that he wanted to be a part of a group of guys who made a name for themselves and could in turn use that to prop up the program’s status with other recruits. “Seeing where Michigan football was going, I’m like, I don’t know, man. The culture should be changed,” Lewis says. “Not trying to disrespect anybody, but that’s how it was and a lot of the guys from the city saw it. Michigan, nobody’s really going there. Nobody’s really talking about Michigan any more, and it’s just crazy.”

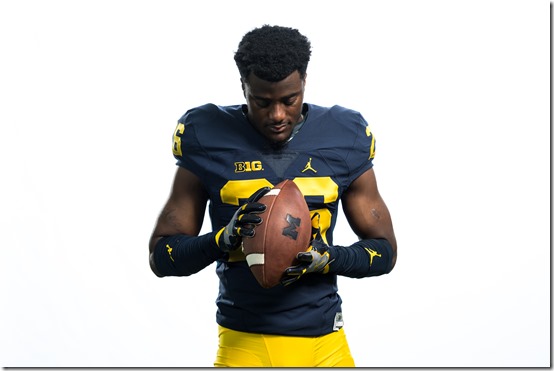

[Heiko Yang/MGoBlog]

Before they could chip away at the culture, however, Lewis and Richardson had to earn football scholarship offers. They both went to Detroit’s Cass Technical High School, which meant playing for Cubs (and Michigan) alum Thomas Wilcher when they began their tenth grade season; at that time, Detroit Public Schools students continued to play PAL football during their freshmen seasons. Wilcher was more than a decade into his Cass Tech coaching career by the time Richardson and then Lewis arrived on his squads, and Lewis describes the program as “a machine.” The machine was engineered to create an eleventh-grade burst, wherein players wait patiently to play in their tenth grade season and then watch their recruiting stock skyrocket their junior season.

The post-sophomore bump was realized for both players, and it started about 800 miles south. Both Richardson and Lewis camped at Alabama before their respective junior seasons and garnered interest from their coaching staff. Both players used this as a confidence booster and validation of the work they had put in while waiting to star at Cass and not much beyond that, as neither afforded the Alabama coaches an opportunity to sink their houndsteeth into their recruitment. Lewis remembers Alabama assistant Bobby Williams pulling him aside and telling Lewis that he was “the next one,” that he could follow in the footsteps of Terry Richardson. Lewis’s mind flashed to Richardson’s recruitment, and he recalls Richardson eventually being ranked the third-best cornerback recruit in the country. His takeaway: if they think I’m the next one here, why not stay home and try to make something out of it?

[Upchurch]

Lewis followed through on that thought, earning and accepting a scholarship offer from Brady Hoke’s Michigan staff. He joined the team for 2013’s fall camp, and he noticed two things in his first few days on campus: the team was really talented, and he wasn’t going to play. He says that he would take a practice off here and there, and gradually his on-field awareness dropped below where he felt it had been before college. By the time bowl practices rolled around, Lewis was tired of feeling out of sorts and felt the extra practices were his time to make a change. “Not going through the motions: okay, I’ve got this guy, or I’ve got zone,” Lewis says of the first changes he made that December. “Understanding what you have to do in those different situations and just taking every detail to heart and applying it, and that’s really what the change was. I wanted to do that, just like I wanted to in little league when I was in track, paying attention to everything I was doing, what was right, what was wrong; the details. That really was the difference coming into my sophomore year.”

Entering the 2014 season, Michigan made sweeping changes to its coaching staff, reassigning coaches to new position groups and bringing in a new offensive coordinator. Dovetailing with the personnel changes was the decision to have the cornerbacks switch to playing press man coverage. Some corners on the roster were left in the decision’s wake; Lewis was not one of them. He tripled his pass breakups from two to six that season, and by the end of the year he had started seven games and was seemingly entrenched as a first-string player.

He may have been performing better on the field, but it’s hard to overstate the hallucinatory feel around the program that season. Lewis says he wasn’t doing as well as he wanted in his classes, and as the season started to spiral downward the players started “taking a break” and, as they believed they weren’t going to make a bowl game, “just chilling.” Lewis finished 2014 with a better stat line than the previous season and burgeoning hype, but within a month the entire coaching staff (with the exception of Greg Mattison) would be fired, and in their place was a staff with a boatload of NFL experience and expectations to match.

Leading up to 2015’s spring camp, Lewis and Nikole Miller, his girlfriend of three years, had several conversations about what things might be like with the new staff. Lewis credits Miller with a moment of self-realization, the moment of humility that kept him from possibly derailing the progress he had made in 2014. “Because he had just started starting Jourdan thought ‘I’m the man’ a little bit. He started kind of feeling himself,” Miller says. “He thought that when Coach Harbaugh came he would still be starting, and I had to really let him know don’t feel yourself too much because Coach Harbaugh does not strike me as the type of guy who would say ‘Oh, you were starting when Coach Hoke was here? Oh, you can keep your position.’ He’s not going to do that. He’s gonna make everybody start from scratch, which he did.”

[Fuller]

Lewis heeded what he terms Miller’s “kick in the butt,” relentlessly worked to learn the details of DJ Durkin’s new defense, and earned his starting position once again; no small feat on a team where scholarship and non-scholarship players entered camp with the same—and only—guarantee: everything would be earned. Harbaugh was the catalyst needed to finally create the byproduct his team (and fanbase) had been searching for. They already had two good compounds—a family-like bond and loads of talent—but it was Harbaugh’s unyielding competitiveness that sped up the process and finalized the culture change Lewis and others had been trying to create.

“JD and Jehu [Chesson] and Darboh, those guys compete every day,” says Richardson, who played with Lewis through Harbaugh’s first season before leaving for a graduate-transfer season at Marshall. “They compete daily; this is not just on Saturday. This is daily, from 3:55 PM, and that’s what changed the culture. That’s what brings people together.” Richardson adds, “Really, the more you compete against each other and with each other, the closer that bond is.”

The 2015 season can be summed up whole-cloth by Lewis’s statistics and accolades: 22 pass breakups, the most in single-season history at Michigan; six pass breakups in a game, which ties Marlin Jackson’s program record; All-Big Ten first team; USA Today first team All-American and Sports Illustrated, AP, Walter Camp, and FWAA second team All-American. The first 59:10 of last season’s Michigan State game was highlighted by his transcendent battle with Michigan State’s Aaron Burbridge and Connor Cook; inch-perfect throws inexplicably uncorked over and over and over, and though Lewis gave up more than he did in any other game that season, images of him hanging in the air with Burbridge time and again, arms over or through Burdbridge’s, floating, denying, are burned into Michigan fans’ memories. The Marlin Jackson comparisons were only natural; Lewis was “the next one.” He had arrived.

Miller and Lewis had to have another heart-to-heart conversation after the 2015 season, though this one was about whether to listen to legitimate outside performance perception and not about realigning Lewis’s opinion with reality. They sat at their dining room table and talked about Jourdan leaving Michigan for the NFL. Lewis told Miller that the thought had entered his mind and he was seriously considering it. She told him there was no way she could date someone without a degree. She told him that one more year would afford him so many opportunities to grow under Coach Harbaugh’s tutelage; he could grow in size, skill, maturity level, even in his knowledge of marketing, a discipline he is enamored with and hopes to work in after (and possibly even during) his football career. The inflection point came in the middle of the conversation. “I said, ‘Jourdan, what if—God forbid—you get hurt your rookie year or even your second year, and you can’t play anymore,’” Miller says. “‘Now you have no football and no degree. Football doesn’t last forever for anyone. You need to be planning an entire other way to further your career while simultaneously playing football. A University of Michigan degree will help you do that.’” Lewis agreed. He would return for one more season.

********

Nagging camp injuries got the 2016 season off to an ill-omened start for Lewis, but not being on the field for three games didn’t keep him from doing what he could to affect change. Lewis is majoring in sociology, which he credits with opening his mind to the history of the world and its people. As he learned more in class, he developed an interest in looking more deeply into the country’s history and the precipitants of social injustice in America. He decided to raise his fist before the playing of the national anthem at football games as a reminder that there are issues that need to be addressed and discussed in this country. He has done this with a simple, peaceful gesture and the platform he’s been afforded, and he does so hoping that he can serve as a role model for the kids where he grew up, that they can see him succeeding on the field and caring about the community, wanting to start important discussions and build relationships, and that he can subsequently serve as a multifaceted role model for those looking for one.

“I always wanted to help people because I was a young kid who always looked up to athletes and different influential people and wondering when are they going to connect to me or different people that I know or are in the same situation as me,” says Lewis. “I didn’t see that a lot. I just want to be one of those guys that can put my hands on some of the guys from the inner city.”

Lewis says that he sees the fist as a way to raise awareness for the unequal treatment of all races in this country, something he says has been a part of the fabric of American history. He quickly adds that this is just the first step. He knows he wants to get into the community and do what he can to help; Lewis’s mannerisms lose their boisterousness, his voice flattens, and his face grows pensive as the conversation on social injustice continues. He posits relationship building as a potential salve, adding that he just wants everyone to see each other in a positive light.

His activism is unsurprising to those who watched Lewis grow up. “If he feels very strongly about something, he’s not going to hold back,” Richardson says. “The one thing I do commend him about is that his approaches to things are not in the form of not being educated on the subject. When JD speaks about things, he is well aware of the situation. He’s just not a guy rambling about it.” Lewis’s PAL football coach William Tandy echoes Richardson’s sentiment. “I would expect him to be a mouthpiece for injustices,” Tandy says. “I would expect him to be a philanthropist, to give back, especially to young males and to low income males because he’s seen it, and he knows what lifelines can do, because he was given it.”

[Fuller]

Still, Lewis wants to do more. His decision to raise his fist before the anthem is calculated to maximize conversation using the additional notoriety afforded a prominent student-athlete at a school the size of Michigan. “You don’t see that discrimination against a certain race because they see you as a public figure and they see you as a staple of a program that everybody’s been a part of, and that’s Michigan football,” Lewis says of his on-campus treatment. “I can’t speak on the regular student or black student’s experience when I’m not even a regular black student, so it’s hard for me. I see the injustices that marginalized populations go through, but it’s hard, especially when being a student-athlete takes a shot at your credibility where you’re never in the situation where you can be in meetings or meet with different groups on campus or go to the President’s events.”

Creating any type of real change is daunting, especially when the scale of the change appears to be so much more than one person can take on. Lewis, though, is undaunted. He earnestly wants to help kids, and he wants to make going to college not some notional dream but a work-driven reality, the next rung on a ladder they have the option of climbing. “He’s going to be creating numerous programs to get kids out of the streets because Jourdan grew up on the east side of Detroit, which is not an ideal neighborhood, and he had football to keep him out of the things the rest of the kids were in,” Miller says. “I feel like that’s the number one place he really feels like he can make a difference and really make a change, if he can just get these kids out of the negative that’s going on in their environment and put them in something positive like extracurricular activities.” Tandy independently arrives at the same conclusion: “Jourdan Lewises come a dime a dozen, but they never get out of the ghettos, they never get out of their neighborhoods because they don’t take ‘God, books, and ball’ as a thing to live by. You don’t hear about them after their 10th or 11th grade year because they’re selling drugs or dropped out or have attitude about discipline. On and off the field, he’s the type of kid where if you said ‘I wish I had a son,’ he would be it.”

********

Miller snickers when she’s told that Lewis says what drives him is his desire to be the absolute best to play the game. To her, football is something he loves, but that kind of bravado doesn’t resonate. She’s familiar with Lewis’s motivation to spark discussion about solving social inequality, to help the youth of Detroit, and to someday start a family; they often talk about their future together. She sees Lewis as a softhearted guy, and she notes multiple times that he defies the arrogant-football-player stereotype. She points out that he stays after every game to sign autographs for kids; that he makes sure he takes time to play with their Yorkie, Jackson, daily; that he will sit in class with Miller when he has time so that they can see each other; that he thinks he’s funnier than her despite her protestations, and that he’s destined to become a “corny soccer dad.”

His personality is different on the field. There, Lewis takes. If you’re a receiver, he will take away your space. If you’re a quarterback, he will take away your window. If you're an offense, he might just take away your ball. He says he’s driven to be one of the best in all aspects of football, and there is nothing that he has done on the field to shroud that with even the smallest amount of doubt.

Off the field, Lewis gives. Miller says that Lewis would literally give the shirt off his back to someone in need (football players really don’t get unlimited Jordan gear, so please don’t ask if you run into him on campus), and that he tries to do exactly that for her whenever they’re out and it starts raining. She adds that she thought she’d see him all the time when they started living together, but that she barely sees him even at the height of the offseason; this past summer, he was always either training with local high school players or working out with Michigan teammates looking to lock down a starting job, guys like Channing Stribling.

Lewis may seem to have a dichotomous personality, but a unifying tenet motivates his actions: he wants to leave things better than he found them. Lewis wants to be remembered as one of the most competitive, hardest-working players to ever call Schembechler Hall home. Away from football, he wants to be remembered as a happy, easygoing guy who had a positive vibe about him everywhere he went and who was always available whenever someone needed help. Simply put, he is driven to create change.

Lewis is talking about his first spring camp under Harbaugh’s tutelage, and in one sentence about earning his position as a starter, the best cornerback in the country verbalizes his anagnorisis: “I can’t go in with the mindset of I’m going to start because that’s complacency, that’s getting comfortable, and that’s where I always mess up.”