Assorted thoughts about the demise of the best thing. This was going to be a UV and then it got out of control.

The bad thing was handled well

Before we talk about Grantland at its best, let's talk about it at its worst. In January of 2014, Grantland published a story about a transgender golf-club purveyor. The story made a convincing case that this person was a fabulist and crackpot, and then at the end threw in an "oh by the way" that this person had killed themselves. It was clear the reason was at least indirectly this very article that you are reading right now. It was breathtakingly tasteless.

The internet noticed, eventually. The backlash to this story was proof that a lot of people will share a longread™ without actually reading it, so twitter was filled with a series of people saying "what a great story" while their mentions filled up with "did you actually READ this?!?!" over the course of the next few days.

Grantland—and by "Grantland" we are talking about Bill Simmons and whatever inner circle told Bill Simmons to hire all the people he hired—took stock. A few days later they responded in two parts. One was an essay by Christinia Kahrl, a transgender baseball writer for Regular ESPN, that detailed the various ways in which everyone had fucked up. The second was an essay from Simmons himself that detailed exactly what happened and how they had fucked up. While Simmons put his name on it because that was what the situation demanded, it's better—more accurate—to read the thing as a collective document from the inner circle that brought Grantland to life. To my eyes it is appropriately contrite, honest, and forthcoming about things.

There are a ton of media companies that will ignore criticism of their work no matter how clearly shoddy it is in retrospect. Not to invoke the dread specter of politics, but a recent three-part NYT series on immigrant-owned nail salons turns out to be about110%bullshit; the Times issued some blather about how they stand by the story and moved on. Grantland seemed to take their problems seriously:

Caleb’s biggest mistake? Outing Dr. V to one of her investors while she was still alive. I don’t think he understood the moral consequences of that decision, and frankly, neither did anyone working for Grantland. That misstep never occurred to me until I discussed it with Christina Kahrl yesterday. But that speaks to our collective ignorance about the issues facing the transgender community in general, as well as our biggest mistake: not educating ourselves on that front before seriously considering whether to run the piece.

When confronted with a major issue the impulse at Grantland was to tell everybody exactly what happened and adapt so it doesn't happen again, something that is a distinct late-Gen-X shift in approaches to these things. That'll be the standard way to handle these events in 30 years. Not so much now.

My wife literally wailed about where Brian Phillips was going to go when I told her that the jig was up, and I still think that Grantland at its worst was kind of Grantland at its best.

[After THE JUMP: hiring strikes, it's not about the money, snobbery, and a third way]

They were 100% in my domains of expertise

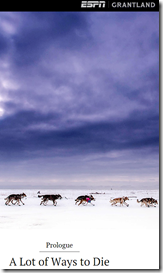

The crazy thing about Grantland is that they hired all the people I would have hired in the areas where I have enough knowledge to offer a solid opinion: Holly Anderson and Matt Hinton in college football, Brian Phillips for the USMNT and the very important Iditarod and Sumo beats, Chris Brown for technical college and NFL analysis, Mark Titus for college basketball, David Shoemaker for wrestling.

I get the impression that everyone else thinks that. Jeff Moss hates everything and since he'd later add NFL columnist Bill Barnwell to this list…

Jonah Keri, the wrestling stuff & Zach Lowe were great. But can we admit to ourselves that almost everything else about Grantland stunk?

— Jeff Moss (@JeffMossDSR) October 30, 2015

…his complaint is that except for the things he really cares about Grantland wasn't that great. Even the insults are backhanded.

Shane Ryan, a former Grantlander, wrote an article for Paste in which he detailed the winding road towards his hire in which he struck on something that rings true: after a brief dalliance with his famous friends (Klosterman, Gladwell, etc) Simmons sought out younger versions of himself. He mostly hired the people who were already writing on the internet because it seemed like they had no choice but to do so, and he gave them a platform, and they crushed it.

At least Grantland's editors should have a lucrative second career finding football coaches for college teams. They wouldn't have hired Mike Riley, that much I guarantee.

The money is not why Grantland closed

In the aftermath, a lot of people wailed like my wife, often on the internet. This spawned the usual wave of people putting on their tweed jacket and circular 1880s glasses to declare that mourning the demise of a good thing is dumb because it didn't make money. Clay Travis was ready to dance on Grantland's grave with a bunch of condescending advice about how he made it. You too can be Sports Guy Fieri if you write a bunch of racist jokes and dress up like a lobster. This is supposed to reassure, I guess? The fact that FS1 is a money-losing entity run by an ESPN castoff largely responsible for the disaster that is First Take who also hired Jason Whitlock escapes Travis, because of course it does.

Grantland existed because Bill Simmons wanted it to and Bill Simmons made ESPN a lot of money. Ditto 30 for 30. ESPN is the kind of corporation that has to be brow-beaten by its most prominent talent to produce anything of worth instead of reality shows about eating tarantulas and Stephen A Smith implying that any woman hit by a professional athlete had it coming. It has billions and billions of dollars. Grantland was close enough to breaking even that however much they were in the red was a drop in the bucket at ESPN. OTL and ESPNW exist because ESPN thinks that the money they don't make is worth the marketing impact they have.

You can tell how concerned ESPN was about Grantland's profitability by the number of ads that they placed in their wildly popular podcasts: virtually zero. If it mattered to ESPN for Grantland to be profitable, it would have been. It just didn't matter enough to the bottom line to spend the effort. It only mattered to public perception amongst the group of people who talk a lot and don't like ESPN much.

ESPN cut Grantland because Skipper had such a deep level of personal animosity towards Bill Simmons that he fired the dude in the New York Times. If ESPN valued the site they could have kept it without any issue whatsoever; that they did not speaks to Skipper's general incompetence. People are just in charge of things because they are in charge of them, and it's clear Skipper either doesn't care about or can't identify quality.

Supremely over the moment Simmons left

Richard Dietsch finally got to talk to Chris Connelly, the guy Skipper tapped to be editor in chief after Simmons's departure. Connelly is able to get through the entire interview without saying anything of substance:

RD:Why did the site ultimately shut down?

CC: Well some of that is not really my determination. I think ESPN has addressed the definitive thoughts on that. My feeling is, for what it is worth, we found ourselves up against new economic realities that maybe had not been foreseen when I took the job. When you are doing a site that you understand is not making money, you kind of understand when times get challenging or there is a new economic climate, you will be scrutinized very closely.

I had a phone call like that once when I worked at Fanhouse. They were on EIC #3, Randy Kim. He was calling everyone up; it took me about ten minutes to reach the conclusion that I was fired whenever they get around to it and Fanhouse was doomed. I basically stopped posting (but still cashed the monthly checks) until they fired me a few months later; Fanhouse went through its "let's hire Mariotti!" phase until someone mercifully bonked it on the head and put it on the cart. I can only assume that most Grantland staffers saw the writing on the wall as soon as Connelly said something like this:

I would say on the sports side I wanted more heart and steel in some of the stuff that we did. Now, it was outstanding, the stuff we did. But I wanted a little of that. On the culture side, maybe a little more [of] how culture is made.

Connelly was there to pet Grantland's head and ask them to talk about the rabbits.

RD:Did you try to convince ESPN management not to close the site?

CC: Sure, yeah. I felt that was my job.

On sports snobbery

Noted Jon Chait antagonist Fredrick DeBoer had a piece on the site in which he crabbed about a certain snootiness that wafted from the sports side of things, in contrast to the generally exuberant pop culture half:

The rejection of a group of hypothetical cultural elitists on the pop culture side of Grantland was always matched by the rejection of the average, conventional wisdom-spouting fan on the sports side. In this, the site reflected a sea change in the coverage of sports: the nearly universal tendency for sportswriters to now represent their work as an antidote to the bad opinions that, they claim, run the sporting world. This belief is clung to even though the online publications these writers work for long ago eclipsed newspaper beat reporters and columnists in influence. The sports blogger Tom Hitchner wrote recently about the tendency of sports commentators to find random, dumb, uninfluential opinions to dispute, even when those opinions are held by almost no one, simply to represent themselves as the wiser and cooler party. Too often, writers at Grantland played into this tendency, engaging in verbal eye-rolling about the idiocy of those who might disagree with them rather than just making their case.

I linked the Hitchner piece myself when some sporps sites tried to spin the online activities of literal children into a story of Online Harassment At The Gates Of Civilization, but the occasional eye-rolling tone from the Grantland writers is not directed at twitter eggs. It's usually directed at studio shows with massive reach, nationally syndicated talk radio, and the color commentators actually doing the game. All of these things have opinions that are eyeroll worthy, from "he just wanted it more" to "Dominicans are stupid."

There are some instances of what Hitchner calls "egg manning"—the practice of finding or anticipating a strawman argument because twitter literally lets anyone say whatever they want—which do rankle. But Grantland did not exist in a world where mainstream sports commentary was frequently useful or reasonable. Joe Morgan's gone; Pete Rose just showed up. A lot of the frustration they espoused was because they'd made a case before only for someone somewhere to bluster through it with platitudes. (I may have experienced this personally.) The hue and cry at Grantland's shuttering is evidence enough they were fighting a battle that had not been won.

There's no better example of this than Brian Phillips piece on Landon Donovan in the immediate aftermath of his Malaysian vision quest:

So, I mean, not to sound too un–Jim Rome here, but at what point do we let humanity back into sports discourse? Isn’t it possible to get fed up with robotronic superstars who “control the narrative,” meaning warp their whole personas to fit some moistly goateed blood-pressure addict’s notion of how to overcompensate for masculine insecurity? Landon Donovan will never win over the guy who wants soulless cadet-destroyers trampling his favorite sports grass. He is maybe the least laser-sound-effect-friendly fast person in the history of professional athletics. But sadness is a thing people feel. Homesickness is a thing people feel. People are mostly uncool and prone to listen to terrible pop music. People get depressed. It’s normal to make decisions based on this stuff.

Donovan got left off the World Cup team by Jurgen Klinsmann largely because Klinsmann was offended by Donovan's failure to be Aaron Rodgers; Donovan went on to lead the league in assists with a whopping 19 and drive the Galaxy to the MLS title. If Grantland people occasionally sounded like garment-rending Cassandras, well, I saw Brad Davis start a World Cup game because they didn't listen.

A third way

Another inevitable and common take in the aftermath:

Is the future slideshows? Is writing things that never exceed more than 300 words all of our destinies? Because I don’t know anyone in this business that is sitting around his or her home thinking, “Man, I’d really love to aggregate some quick-hitting content that creates engagement across several platforms.”

As an almost completely unemployed sports writer seeing another wave of sports writers that are almost all better than me at this become unemployed, I wonder what’s next for me and the business at-large. Do we all need to start writing for the guys with the Volquez jokes? Is that what sells? I’m all for debate when it’s fun and smart, but are Stephen A. Bayless Shoutfests the only thing that turns a profit? Is there no room for a 4,000-word oral history about the first time Michael Jordan ate a McRib?

I think there is another way, and you're looking at it. MGoBlog is the full-time occupation of three people and has a constellation of paid contributors. Our tentpole content consists of 5,000 word game columns, 10,000 word "Upon Further Review" game breakdowns, 4,000 word breakdowns of upcoming opponents, etc., etc., etc. There are a lot of words.

I was going to talk about how we made that work but that expanded into its own post that'll go up later. I'm just saying: if you pick the right thing and hit it hard and your brother knows his way around a bash shell, you can have yourself a nice career. Just make sure you pick your brother wisely.

On leaving

I get asked sometimes about what happens when I go do something else. The answer is I don't. I have been approached to sell or move the site many times and I've never seriously considered it. Almost all prospective purchasers have no idea why this site is successful, and eventually that would lead to a bunch of overhead I don't want to do, a Simmons diva phase, and then an exit.

Even if the current boss is a good boss, maybe he goes and does something else, and then it's someone else who you don't know and doesn't know you. This is a good setup, one in which the tablecloth doesn't get yanked out on a Friday afternoon. I'd have to be an idiot to change it.

On Grantland

For four years you could type Grantland.com into your browser without having any idea what you could expect other than the fact it would be worth your time.