Five on five. [Upchurch]

When news broke recently that Jabrill Peppers was moving to safety, Brian threw up a quick explanatory post, Why Peppers Might Be A Safety, talking about how modern spread offenses dictate modern quarters defenses, which in turn dictate that the safety over the slot is the glamour position du jour.

An offensive innovation like the zone read will open up the entire book again as coaches figure out ways of running all the things they already like out of new looks, new play-action, etc. But defensive innovation, with a few notable exceptions, is much more reactive.

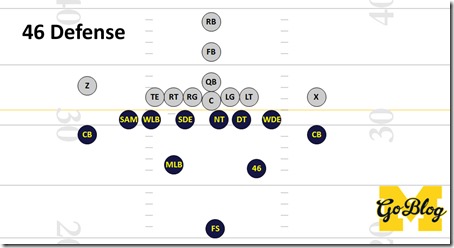

Often what we call a "new defense" is just rediscovering an old, unsound thing that takes away the thing offenses are doing these days. The 46 defense was bringing a safety down. The zone blitz was having a defensive end playing coverage. The Tampa 2 had a middle linebacker responsible for deep middle coverage. The 3-4 made three linemen responsible for six gaps. And the hybrid man/zones of today put your deep coverage into the middle of the run-stopping game.

The way a defensive innovation becomes a sustainably great defense is great players. Dantonio's quarters dominated college football with a string of NFL-bound defensive backs. The 3-4's proliferation through the NFL was accompanied by a rush on anything that looked like Vince Wilfork. The Steel Curtain (the first Tampa 2) was built around Jack Lambert. Miami (NFL Miami)'s "No Name" zone blitz defense had a 6'5/248 lb. track star named Bill Stanfill at WDE. And the '80s Bears could pull off this crap:

…because that "46" was the jersey number of one Doug Plank.

You don't need to be a football guru to see what made the 46 defense tough: there are eight dudes in the box, six of whom are just a few steps from the quarterback. Running into a stacked box is futile (DO YOU HEAR ME? DO YOU HEAR ME, AL?!?). You can try to identify who's blitzing and throw to holes in the coverage before they arrive, but you'd better have Dan Marino.

[After the jump: how to 46 a modern offense]

The Impact of a Dynamic Safety

One of my most visited bookmarked Chris Brown articles is How Troy Polamalu and Ed Reed Changed NFL Defenses.

| Peppers-Like CB Recruits (Detail—>LINK) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Player | School | Size | Career Summary |

| Justin King | PSU | 6'0/183 | Size and speed were overrated, but immediately an effective nickel and early NFL corner with a vagabond NFL career |

| Demetrice Morley | Tenn | 6'0/176 | Nickel then moved to safety, was effective until career derailed by off-field issues |

| Eric Berry | Tenn | 6'0/194 | Nickel then star safety probably deserved Heisman, NFL All Pro |

| Patrick Peterson | LSU | 6'1/197 | Nickel then boundary corner, fringe Heisman candidate, NFL All Pro at CB |

| Dre Kirkpatrick | Bama | 6'2/180 | Reserve on deep roster then bestial boundary CB. Backup NFL CB. |

| LaMarcus Joyner | FSU | 5'8/192 | Safety/nickel, led resurgence of that defense. Rising NFL safety |

| Charles Woodson | Mich | 6'1/195 | Blue know it. |

In it he describes an entirely different philosophical approach that Buddy Ryan used when deploying the 46 defense as an answer to the West Coast:

The theory behind the 46 was that offenses seized the advantage because defenses let them dictate terms. For 30 years, defenses more or less tried to match and mirror offenses based on personnel and alignment, but they couldn’t keep up. Ryan planned to negate this advantage by force — the 46’s simple guiding principle was to kick ass.

Kicking ass is usually a luxury of teams that have a decided advantage in player recruitment or retention; otherwise you're just playing rock-paper-scissors with the other coordinator.

The 46 itself was an aggressive formation that worked because it could line up so many players so close to the quarterback but still defend the deep pass because Plank could; once offenses began to spread out, quarterbacks again had the time and space to work through their choreographed progressions, and defenses were forced to get bendy again to cover all of that open space.

Football guys hate bendy. Walk into any defensive guy's presser in America on any given day and you're more likely than not going to hear him talk about wanting to "get more aggressive."

The Sliding Scale of Aggressive Quarters

As soon as the spread offense took hold, defensive coordinators began dreaming up ways of kicking its ass. The Greatest Show on Turf exploded onto the scene in the 1999 season; just one year later the offensively anemic Baltimore Ravens won the Super Bowl, giving up just 20 points in four playoff games.

The reason the Ravens could play super-aggressive against the run while remaining sound against spread passing was Rod Woodson, who could set up in a linebacker-ish spot and still get back to play deep. But that Woodson was at the tail end of his career; the Ravens sustained their dominance after Rod by drafting Ed Reed.

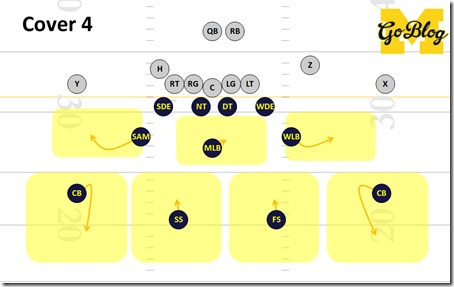

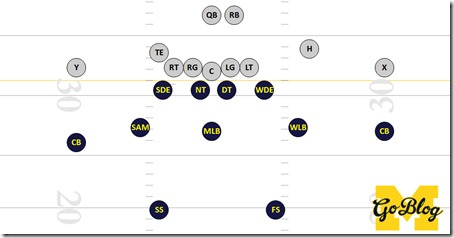

That defense took its name from the most bendy defensive look: cover 4:

Nobody's sending four verts against that, but you can run against it all day. What made it "Quarters" was this look was hybridized with Tampa 2 into a read scheme: if the inside receiver went vertical the safety would be there to catch him (left side of the gif below), and if he didn't the safety was free to cover the outside receiver over the top (right side of the gif below).

Aside from the "pattern matching" (Saban's term for it) of coverages, the additional benefit of Quarters was the safeties didn't have an immediate threat to cover, and therefore could peek in on the run game.

Nine Guys Versus the Run

Because of this, Quarters defenses like to claim they put "Nine in the Box," but what they really mean is they ultimately have nine defenders involved in their run fits. When you run this scheme, you quickly find the cornerbacks are basically playing man defense, especially since they're responsible for whatever those outside receivers do in the first few steps of the play. They can't really do that and play a run gap, but those safeties can.

Well the first rule of stopping the run game: how fast does the tackler get to his hole? If you're starting out loose, it's going to take some time before those defenders get to where the run's going, by which time the blocking is set up and the ballcarrier is picking his way to the hole.

The tighter you get, the more "aggressive" you can be against the run, the more effectively you can blitz, and the more you're in a position to dictate terms to the offense, i.e. kick some ass.

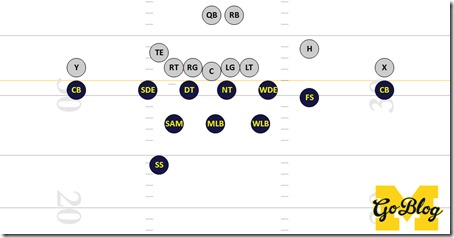

Starring Peppers as Ed Reed

We've come back around to something very much like 46 defense, and like 46 defense, that safety is sitting in a lot of space. This is why Quarters can only be as aggressive as its safeties' ability to cover the slot seam.

That "FS" in the diagram above is matched against the slot receiver, who through the history of the spread evolved into the havoc-wreaking star of the offense. Rodriguez found athletic little bugs who were death in space and blocked like mountain goats. Urban Meyer had them be that and super-smart, well-trained route-stemmers who could get to open space no matter how the defense played them. Holgo and the latest offenses had them be that and that and the other thing, and a supreme deep threat. All of that was toward the same goal: get that m'er f'ing defender away from my run game!

So you see why having Ed Reed lets you get away with ass-kicking, because that guy can reliably track down a slot bug in space, can't be blocked by anyone in the bell of normal human size distribution, is too agile to lose with clever route running, and will win any footrace against any receiver you try to send over the top of him.

This is what Michigan is going to try to do with a redshirt freshman who by every possible indication is going to be the best damn football player Michigan has fielded since Charles. How much it will kick ass will largely depend on how much Peppers can.