via Bentley

Kelly Lytle's book, To Dad, From Kelly, is a reflection on his relationship with his late father, former Michigan All-American Rob Lytle. The following is an introduction highlighting Rob Lytle's bond with Bo, followed after the jump by an excerpt from the book, titled "Lytle Would Play." You can visit the author at www.kellylytle.com.

Introduction by Kelly Lytle:

It was the day before the Game of the Century between #1 Ohio State and #2 Michigan. I was 24 and working on Wall Street in lower Manhattan, and spent the morning with my attention fixed on my computer screen reading previews of the next day’s showdown. By late morning, I had read that Bo had collapsed and been rushed to the hospital, the prognosis grim. I searched for any detail I could find, ignoring the routine commotion of the trading floor. Then my phone rang.

"Kelly," Dad started, his voice soft and weak. "Kelly, I just lost a father." Silence.

"Kelly, I loved him," Dad finally said.

|

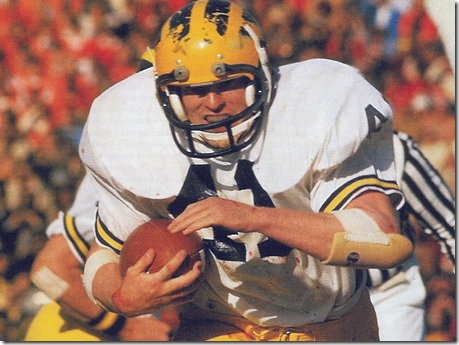

| Lytle's playing career left him battling lifelong injuries, but true to form he wouldn't let that sideline him. [via http://kellylytle.com/] |

My father and Bo met in 1971 when Dad was a high school All-American for Fremont Ross in Fremont, Ohio. At the time, college coaches around the country were promising Dad the world. Bear Bryant apparently once said: "Rob, how 'bout you come visit Alabama so one of our belles can show you some southern hospitality." And Woody Hayes claimed that he would run the wishbone offense so Archie Griffin and Dad could share carries. Bo, though, took a different approach.

"Rob," he said, "You’ll never be as great again to these coaches as you are right now. At Michigan, we have six running backs. You’ll be number seven if you come here. Whatever happens after that is up to you."

Dad eventually narrowed his college choice to Michigan and Ohio State. When Dad phoned Woody to inform him of his decision to attend Michigan, Woody simply said, “We’ll see about that.” Not long after, Dad found himself in his living room face-to-face with the Buckeye leader. “If you’re committing to Michigan, you better say it to my face,” Woody demanded. So he said it to his face. Bo's honest challenge had made its impression.

The next four years cemented the relationship between Dad and Bo. In Bo, Dad had a mentor who preached the team over the individual, and a coach whose sermons about modesty and determination weren’t just words but gospel. In Dad, Bo had a talented runner who believed in self-sacrifice, a star who played through pain so often that for years after in the Michigan training room hurt players would have to hear the words “Lytle would play.”

Michigan won 28 games from 1974-1976 and played in the Orange Bowl and Rose Bowl. In 1976, they shut out Ohio State 22-0 at the Horseshoe to win the Big Ten Championship. Dad ended his career as Michigan’s all-time leader in career rushing yards with 3,307 (he’s now 8th), won Big Ten MVP his senior season, and finished third in balloting for the 1976 Heisman Trophy. Still, I believe these accomplishments were secondary for both Bo and Dad.

Every conversation I’ve ever had with Dad’s Michigan teammates settles on one topic: that when Bo asked Dad to play fullback to bolster the offense, he willingly sacrificed carries, yards, and his body to better the team. For this, Bo often called Dad the “greatest teammate” he ever coached.

While growing up, Dad never mentioned his touchdowns and records or wins and losses. Instead, he preached the values of Michigan football. “Every day you either get better or you get worse, you never stay the same,” Dad would often say, usually punctuating it with a reminder that “nobody is ever as important as the team.” I often laughed away his comments as trite.

Now I can see them as the hallmarks of a man dedicated to placing others above himself. Playing football, especially from 1973-1977 at Michigan, shaped my father. These years strengthened his resolve. They fortified his sincerity. They wrecked his body. The game left him physically beaten and emotionally broken when injuries forced him to retire. He shouldered this pain the rest of his life.

Dad died on November 20, 2010, eight days after his 56th birthday, and three years and three days after he'd lost Bo. I lost my best friend and the man who most influenced me. To Dad, From Kelly is my attempt to remember my father through the lessons he taught me and the questions that went unasked and unanswered between us.

[After the jump, an excerpt from Kelly's book. Fair warning: it's emotional]

I always marveled at my dad’s hands. If I looked hard enough, I could imagine them in their prime, one powerfully clutching a football and the other jabbing at an opponent in his path. In real life, though, I saw his hands as a gateway for suffering. His bloated and arthritic fingers pointed in ten directions. Each one carried a combat story from his days playing football.

|

| A tribute letter became a tribute novel. [via http://kellylytle.com/] |

I watched Dad labor to get through each day for almost three decades before he died. I can remember him trying to stand. He’d push himself off a couch or chair, make it halfway, and falter. His knees would wobble and silent screams would seem to wail from his eyes. He’d brace himself against a headrest or nearby table and finally stand. I’d watch, then forget. The most familiar sights are the easiest to ignore.

As Dad’s life neared its end, the sport he loved had reduced this once celebrated athlete to limps and winces. But Dad never mentioned the pain; complaining wasn’t part of his makeup. Besides, I don’t think he felt he had any right to grumble. As a boy, he had dreamed of playing professional football, and he had realized his dream. By his own admission, he accepted the costs with a single regret: that his myriad injuries kept him from reaching his potential and forced his retirement before he was ready to say goodbye.

Now, with his life abbreviated at the age of 56, I wish I could ask Dad one more time if he still believed all the treatments, operations, excruciating mornings, prescription drug dependence, and even his early death remained the acceptable collateral damage for an athletic goal achieved. Would Dad accept the same deal he made with football’s devils if he knew the real outcome?

To understand my dad one needed to recognize that his life had a singular mission. Growing up in Fremont, Dad told his parents and two sisters that he would play professional football. To him, this pronouncement wasn’t a boast but a fact. He charted a course to the NFL, and he prepared himself to endure whatever abuses and sacrifices were necessary to achieve it.

In playground basketball games against older neighborhood kids, he wrapped ankle weights above his shoes, believing they would strengthen his legs enough to withstand the punishment of the career he envisioned. Later, in junior high school, he started lifting weights and running sprints with the older players on the high school’s varsity team. He craved the satisfaction that came with challenging the bigger, stronger, and faster high school kids. “Couldn’t get enough of it,” Dad told me years later. “All I wanted was to keep practicing. Every day, hell, every minute. I loved football, Kelly.”

People doubted his abilities. Find another dream, they said. You're too small, too slow, or too white ever to play in the NFL. But Dad refused to listen. “I didn’t care,” he said. “Nothing was stopping me. Nobody knew how hard I would work to get there. Nobody realized how much I had to play football.”

I wonder if the same obsession would consume Dad if he knew how life would dead end. Maybe it doesn’t matter. Football chose Dad as much as he chose football. He loved the sport as a parent loves a child, unconditionally.

High school, college, and NFL teammates praised Dad. Throughout my life, I heard their stories about how he persevered through injuries and dedicated his body to the team. Legendary Michigan football coach Bo Schembechler called him one of the toughest players he had ever coached, saying that Dad absorbed abuse while playing like an “ugly outsider trying desperately for the last spot on the team.”

Following Dad’s memorial service, I heard from several former Michigan players that Coach Schembechler judged future generations of Wolverines by their willingness to pry their battered bodies from the training room table for another grueling practice. To coax players off the injured list and onto the field, the coach would often say, “Lytle would play.”

After Dad’s death, his teammates echoed this sentiment in their tributes, many calling Dad the best teammate they ever had. Others stated they had never played alongside a tougher man. At Michigan, Dad might have been an All-American and Heisman Trophy finalist, but self-sacrifice is what lingered as his most respected trait.

The question I have is whether the toughness that earned him the admiration of coaches and teammates was worth it. I want this answer because I saw unrelenting suffering become the cruel counterpart to his earning such compliments.

Whether the result of pride, masculinity, his passion to succeed, or a combination of all three, Dad believed that reaching his football goals required a full-speed charge through any obstacle. If finishing a game meant sprinting back to the huddle for a series of plays that he might not remember, after enduring a collision that his body and brain would never forget, he willed himself to the task. If the chance to play depended on receiving another painkilling injection to mask burning joints, he let the doctor jab the medicine into his body. Knees, toes, or shoulders, Dad didn’t discriminate. He welcomed every shot with a smile. The shots brought him closer to returning to the field.

Football’s stranglehold on Dad demanded that no alternatives existed. Many years after he retired, he remarked that he still longed for the camaraderie of joining his teammates in the locker room, laughing while having their ankles and wrists taped before a game or practice. Despite the carpenter’s set of screws and pins inserted into his body, he craved one more play. It seems that no roadblock could have stopped his life from colliding with football’s seductive force. The game gripped him as nothing else in his life ever could.

With success, however, came consequences. By the time he died he had an artificial left knee, an artificial right shoulder, persistent headaches, a mind that had begun to distance itself from reality, vertigo, and carpal tunnel so severe that it stripped all feeling from his hands as he fought to sleep at night. Time and age faded the scars slicing through his arms and legs, but his spoiled joints and pained gait remained. When Dad died, his body was a junkyard of used parts, a collection of leftovers from a sacrificial offering to his pagan god. Teammates and opponents praised his determination, but our family now lives without someone whose body failed him too soon.

I never felt for a sport, job, or anything, really, even a measure of what Dad felt for football. He worshipped the game and grieved without it every day following his retirement. Perhaps it’s unfair for me to question his devotion since it isn’t something I can completely understand. Before passing, he told me on countless occasions that he accepted his physical suffering because the toll came with playing the game he loved. I suppose that in his eyes, the desire to reach the pinnacle of his sport meant nothing without a willingness to punish and stretch his body across the goal line to achieve it.

For a long time, I agreed with his perspective. But everything Dad had said about accepting the pain he collected from football changed for me on November 20, 2010. A heart attack too powerful for his body to overcome became his final reward for the toughness admired by fans. On the day he died, his daughter lost her father, his wife became a widow at 55, and I lost my best friend. In the aftermath of his death, I question whether Dad would still choose football if someone had warned him of the consequences. Except I’m sure I know the answer.

“Yes,” Dad would say. “All I want is one more play. And maybe one more after that.” Then, he would smile.