Things that happen against Rutgers’s defense can’t be taken too seriously. They’re playing a former Brady Hoke cornerback as a SAM in a 4-3 under, which means he’s taking on fullbacks and pulling guards. Their other edge guy is Kemoko Turay, an athletic dude who’s still rather unfamiliar with the game of football, and who’s functioning now as a WDE/OLB hybrid. Their WLB is by some distance the worst player I’ve scouted this year. One of their safeties is 5’9” and was their leading receiver last year and just joined the defense three weeks ago. The other safety is worse.

But their three interior DL are pretty stout. This made the Rutgers game uniquely suited to Michigan’s power running game. You know Power, Michigan’s base play under Jim Harbaugh, Brady Hoke, Lloyd Carr, and Fielding H. Yost. God’s play. Power.

Power and its close cousin Counter Trey are a lot like Inside Zone in that as a base play there are a ton of ways to run it depending on what the defense is showing and who appears where.

The concept is simple enough: 1) Block down on as many line defenders as you can to seal them inside, 2) Pry open a gap between them and the playside edge protector, and 3) Swing around a backside blocker into the point of attack to hit the first guy he sees. Win those downblocks and kick out the edge and now it’s just a race to see if your meat and the ball can get through that gap before the defense can plug it.

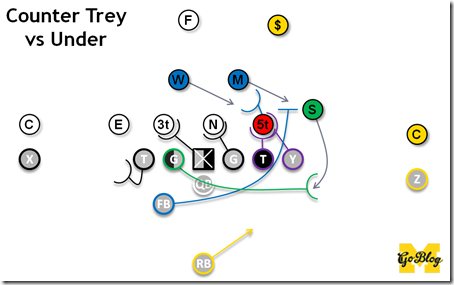

On “Power” the swing man is usually your backside guard, while a fullback or H-back is the “trapper” or pry-bar trying to blow the edge open. On “Counter Trey” those guys swap jobs. Note the backfield action is like a run to the right side, and that the pulling guard is wiping out the edge:

Counter Trey. (The guy Ben Mason blocked into the endzone is an awful, awful player, but still: braaaaawwwwrrrr!)

[Hit THE JUMP for what Rutgers did, and how Michigan didn’t have to respond because an answer was built into the play did I tell you this is God’s play?]

-------------------------------------

RUTGERS KNEW THIS WAS THE PLAN

As predicted when we did the scouting on these guys, it was clear to both teams that Michigan was going to run a ton of Power and Counter. That allowed Michigan to negate the three interior linemen by regularly blocking down on them. That put the success of the plays on how well Michigan’s guards and fullbacks could dislodge Turay and Douglas, and push the linebackers around.

So what do you if you’re Rutgers and don’t want this to happen?

SLANT!

SLANT!

On both of these Kugler could do a better job—the slant merely took away the advantage he got from his downblock and made it a fair fight. Still, by negating that advantage, the defense is winning back the matchup battle, giving their good DTs a chance to beat a block and make a play in the backfield.

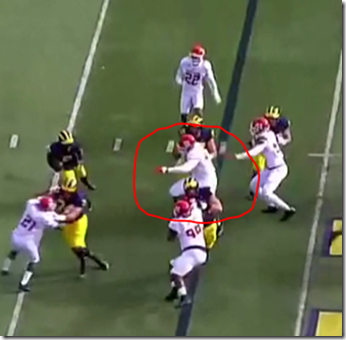

Rutgers was pretty determined to take power away from the get-go. This below is the game’s second snap and Michigan’s first power run of the day. Before you hit play notice that the defense is baiting Michigan to run to this very spot, with a huge gap between their playside DE and the nose tackle (who’s head up on Kugler):

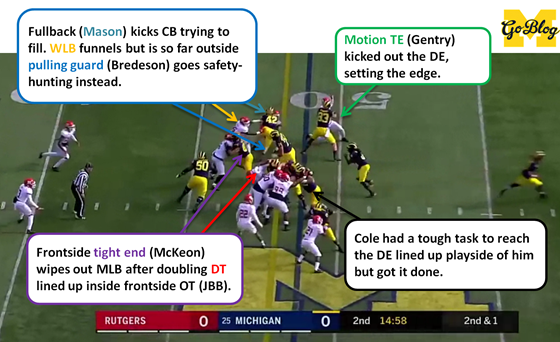

I drew it so you can see where everybody’s assignment ends up:

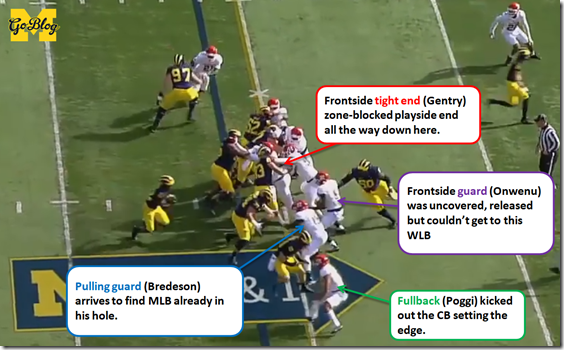

The good news is the blockers all adjusted properly. Gentry (red) correctly read that the DE was slanting inside and stayed with him, not getting a seal but creating plenty of space to run by on the left edge. Poggi (green) flared out to meet Rutgers’s edge protection and found a cornerback to set the other side of that hole.

The rest of the story is the guards and the running back versus the linebackers. Onwenu (purple) had nobody over him and released but because of the defensive playcall the WLB was already scraping over toward the hole; he would show up unblocked to make the tackle. The slant-scrape action also meant the MLB met the puller, Bredeson (blue) right smack in the middle of the gap.

So Rutgers invited this by offering a big wide gap (the space between red and green). But with the LBs pursuing so hard to the frontside, by the time the play develops there are two linebackers in that gap with one lead blocker to deal with them. Higdon can only run into the WLB and let momentum get the first down.

Or can he?

-------------------------------------

CUTTING TO THE BACK SIDE

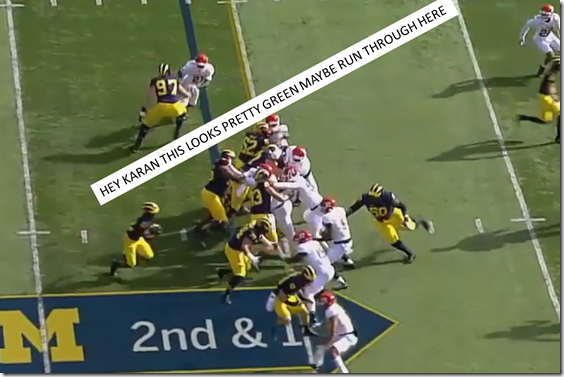

If you’re wondering if a backside cut is part of power running, why yes it is. Because coaches like control a lot of them teach running backs how to read power like “A-B-C” i.e. read the gaps from the inside-out. With power running however, you’re more likely to get a huge mass of moving bodies in front of you. Power running is like zone running in that patience is rewarded. And part of that patience is, indeed, checking first for that backside cut.

That’s not such a simple thing to learn. As a running back you’re highly invested in the point of attack, which defenders are going where, and how those blocks are going. Taking your eyes off of this interesting stuff to see if a guy getting blocked down actually got blocked down is tedious. But it can also be rewarding, and with Rutgers slanting so often in this game it became doubly so.

By the fourth quarter Michigan was hitting that backside cut with regularity off of Power…

…and Counter.

And backside counter:

And counter versus weird run fits:

Watch LB #6 overreact to the pull; this was his gap.

These big cutback lanes were open because Rutgers was slanting their defensive line frontside and Michigan was adjusting on the fly. The backs just have to see the slant and they’ll know the cutback lane is open. This is where all that inside zone training helps: the backside guys might lose a downblock to a heavy slant, but can keep riding that dude and open up a lane behind him. Any linebackers who read the pull and jumped playside of a releasing playside OG are now totally wrongsided.

The guard (or the fullback on a Counter play) as a “hit whatever you see first” dude can adjust as well. On the two Evans runs above, Ben Mason saw a slanting DT was making it past the downblocks and used himself up to seal that backside lane.

Like inside zone, the offense’s ability to adjust Power runs on the fly makes it a play you can use all day…or at least until the defense starts activating the safeties against it and blitzing linebackers into gaps the defensive line doesn’t have covered. Provided the offense has a semi-functional passing game* to punish that, a good Power team can run to the ends of the Earth.

-------------------------------------

* [

Hey BP, BP, won’t you smile for me?]

-------------------------------------

FLIPPING THEM OFF

The other thing Michigan did to counter the slanting was to balance the line with heavy and goal line formations. Now the defense has a choice to make: do you slant to the side with the tight end, or the side with the other tight end? If you choose incorrectly…

#17 made a business decision.

Here’s how this unfolded:

Going with a balanced line also made it possible to flip Rutgers from an advantageous position to not that. After the first quarter the defense decided to hell with fancy crap: let’s put our 5-tech over a friggin’ guard. Michigan was like: “fine, we’ll go the other way.”

ahhhhhhhhh, trap-bam, thank you ma’am

Motioning Gentry across here flipped the strength of the formation. But the line didn’t shift, meaning Rutgers has found themselves facing a goal line formation with an over front.

This works despite Onwenu blocking nobody, partly because the WLB (I told you that guy isn’t good) got too far outside while setting the edge and missed an ankle tackle as Kareem ran by him.

-------------------------------------

GETTING GOOD

You have to wonder what Bredeson thought there by passing up the WLB. Standard coaching procedure would say hit the first guy who shows. The WLB is the first guy who shows, and Bredeson is like “Nah, you Upham.”

And this is totally correct. Rather than jamming up the lane with himself and the WLB, Bredeson gets himself clear through the hole and hits a safety. Kareem Walker blows by the WLB’s tackle attempt. Kareem is big. The WLB is bad at football, set up too far outside, and not worth the mess of a hallway fight.

Some teams that run power are trying to wall guys off. Others are focused on blowing dudes off the line. The great power teams however are those that can do a ton of different things on the fly. I can’t tell you this for certain but I bet Bredeson was in the film room one day and Drevno pointed out that sometimes you can do this sort of thing. Getting to that film room session however takes running power so many times that the coach doesn’t have to worry about adding more thought processes to the all-important basics.

Michigan’s swing blockers were passing up shots at these funnel defenders all day. So were outside blockers. Receivers routinely went for crack blocks on safeties (or linebackers) and left their cornerbacks to try to take out Michigan’s running backs alone. When they can get a block on those guys it opens up huge gainers.

Watch Schoenle (#81 top of the screen):

The difficult part is getting to the point where the players are so used to running it that they are making the correct adjustments mid-play: you have to get past “Where’s my block?” before you can get to “Kareem can beat that guy.”

Michigan’s offense put on a power clinic against Rutgers. That’s both expected and encouraging, since the things that should work against Rutgers most of the time ought to work against a real Big Ten defense a fair amount of the time. Michigan’s power running game looks like it’s there. They’re good enough now that if the defense has to play them honest—nerfing slants with backside cuts, formation flips, and varied blocks (e.g. Counter Trey), and keeping the safeties and linebackers from coming up too hard with a passing game that won’t routinely screw itself—Michigan’s power runs can be a consistent gainer.