This series is a work-in-progress glossary of football concepts we tend to talk about in these pages. Previously:

Offensive concepts:RPOs, high-low, snag, mesh, covered/ineligible receivers, Duo, zone vs gap blocking, zone stretch,split zone, pin and pull, inverted veer, reach block, kickout block, wham block, Y banana play, TRAIN, the run & shoot

Defensive concepts: The 3-3-5, Contain & lane integrity, force player, hybrid space player, no YOU’RE a 3-4!, scrape exchange, Tampa 2, Saban-style pattern-matching, match quarters, Dantonio’s quarters, Don Brown’s 4-DL packages and 3-DL packages, Bear

Special Teams: Spread punt vs NFL-style

----------------------------------

Michigan’s gameplan last week was to build around one of the most consistently effective offensive plays in college football: the Mesh. Now listen, everybody meshes. It’s the favorite play of schools with questionable quarterbacks, and the base play that the air raid offense is built from. Unless you’re really good at fades mesh is probably your go-to goal-line passing offense. I know it probably wasn’t the plan, but a mesh-based game was also perfect for O’Korn.

THE CONCEPT:

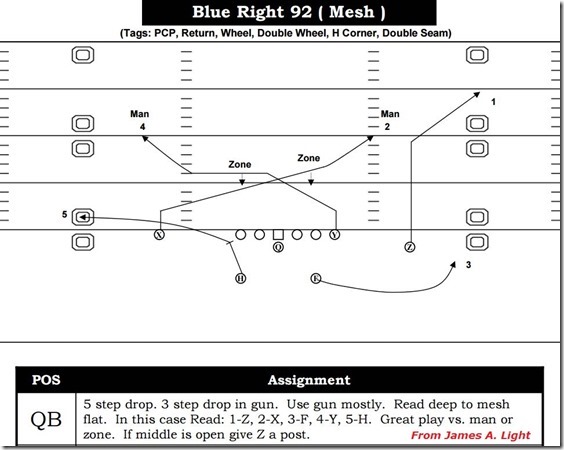

Also James Light found Mike Leach’s 1999 Oklahoma Sooners playbook:

At its core, Mesh is a short, easy, and rather cheap passing play designed to cross a pair of drag routes in hopes of creating a ton of traffic for the coverage. Imagine the above with the strong safety ($) trying to trail the blue tight end: what hope does the red cornerback have of staying with the red tight end with all of those bodies around?

That of course is if they catch man defense. If it’s zone, well, crossing routes are zone-beaters: just run the receivers into open ground and have them sit down for easy yardage.

[Hit THE JUMP to see how it worked]

-------------------------------------

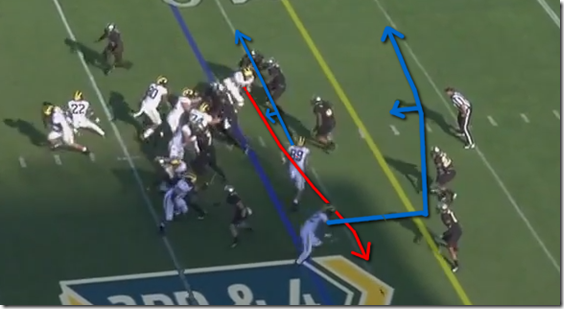

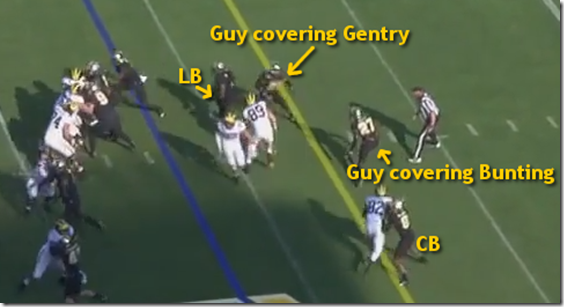

All three tight ends run crossing routes. The “Mesh” we’re talking about is how the routes of Gentry and Bunting help each other. If you catch man defense, you’re expecting the guy covering Gentry to get stuck behind him and ditto the guy on Bunting. When those routes cross the poor coverage guys end up in a ton of traffic. Quite often—and this is by design—the mesh becomes a pick play: one guy crossing from one direction will path himself right into the lane the guy covering his crossing buddy meant to take in order to stay on top.

And lo and behold Bunting becomes an obstacle. Whoops, sorry about that fella:

Over this Eubanks is running a clear-out route. See him run right at the cornerback lined up over him, threatening to go on a post route or fade to the corner or stop inside—whatever I’m gonna do you’d better pay attention to me! That’s to get the cornerback to commit inside—if he doesn’t Eubanks will come open behind the safety reacting to what’s beneath and it’s an easy throw for all the yards.

For O’Korn it’s a very easy read. He keeps his eyes on the mesh point, expecting Gentry to pop open from the mesh, and watching the safety and linebackers for where the soft spot is going to be. On this one Purdue blitzed the SAM, so Gentry should have a boatload of clear space to make the catch and a one-on-one battle of athleticism with the cornerback for the rest.

The CB isn’t going to stick on Eubanks here so the window of opportunity lasts only so long as the defensive back is deterring a throw behind the safety, plus that CB’s reaction time, change of direction, and speed to the edge, versus how fast Gentry can bring in the catch, accelerate, and lope downfield. Michigan’s hyper-athletic tight end versus Purdue’s 2-star cornerback ends is a 6-point talent mismatch.

In this example Michigan’s backs both caught blockers, but the way this is designed is often with an RB check/flat route to each side. That should clear out any OLBs hanging around in the flats if they aren’t doing the offense a favor by blitzing.

-------------------------------------

WHY ARE THERE SPIKES ON YOUR ROUTES?

Because you don’t just run crossing routes to attack just one spot. Against man coverage a crossing route becomes a race to create (rub-assisted) space, but if you’re crossing through zone coverage why run into someone’s zone if you’re already between zones? The more advanced a team is at running mesh, the more the quarterbacks and receivers will start picking on spots between the zones, with the option to cut off a route if there’s space between the linebackers. Harbaugh’s passing game uses these reads a lot when he’s got receivers and quarterbacks capable of using them.

Here Eubanks spots the safety (#27) following Bunting—rather than following the safety, Eubanks can sit down on his route, and now if Gentry’s not open, Eubanks will be.

-------------------------------------

WHAT ARE THE MOST IMPORTANT INGREDIENTS?

1. A good interior run game that gets those linebackers stepping forward. Michigan ran play-action here from a goal line formation, and Purdue was dead-set on stopping a run to the point of running their SAM into a slide protection situation that put the majority of M’s offensive linemen to his side (RPS+1). In a normal situation there are linebackers adding to the traffic here, and the more they’re dropping back into protection the faster those LBs can react and attack on routes crossing in front of them. Getting those TEs running behind the linebackers is key.

2. Athletic tight ends unless you’re going full air raid. How well Gentry and Bunting and Eubanks threatened the guys tasked with covering them played a big role in the success of this play. One of the reasons this is such a staple play for MSU and Wisconsin is those teams have had excellent pass-catchy tight ends. If your TE gets hung up at the line it’ll throw off the mesh’s timing. If your TE has to stop and concentrate on bringing in the pass, or can’t accelerate worth a damn afterwards, that gives the defense time to react and swarm—you’re already running this near the line of scrimmage so a tackle near the catch point is zero yards. On this play Gentry’s huge length made it possible for O’Korn to wing it off his back foot, and Gentry still brought it in without leaving his feet, then outraced a 5’9” dude.

Now, you’ll see air raid teams run mesh all the time with slot receivers because those receivers are well-trained experts at their pick routes, and finding open ground, and can then be used as downfield threats and regular slots—blocking isn’t as important because the whole point of the air raid is to spread out the DL then pass to open dudes before the pass rush arrives, while runs are by definition between the tackles. But in the context of a [what used to be] pro-style offense, tight ends are best, not just because they’re huge and ge t-in-the-way-y, but because the further your mesh guys have to go to create the mesh, the easier it is to pull off.

3. Solid interior pass pro. Mesh is an intermediate route development. You don’t need your edge protection to hold forever, but it’s not like a slant or screen where your OL hardly matters. This means your interior pass protection has to be able to prevent instant pressure consistently. Remember, you’re using up the tight ends on routes, so the OTs are going to be alone on the edge. As long as there’s a pocket to step into, that should be good enough. Here Runyan got overwhelmed by a speed rush, and while he got his guy down eventually, the dude was now at O’Korn’s feet so the quarterback couldn’t (or didn’t feel comfortable …-ing) step into his throw.

By emphasizing those three areas Mesh will allow an offense to de-emphasize things like how many reads a quarterback has to make, how deep/hard does a quarterback have to throw, and how long the pass protection has to stay hale, and most of all whether receivers can get open. Michigan State (since Cook) and Wisconsin adore this play because they base their offenses on interior running, and will try to keep their quarterback’s job simplified down to one easy throw that’s almost always open. Also they don’t have receivers who’ll put the fear of death into opponents, so they’re likely to face a lot of man-high defenses who want to shoot their linebackers upfield at the snap. Mesh does all those things.

-------------------------------------

IS THERE A DOWNSIDE? Mesh can break for a big play like any play can, however at its heart it’s a play designed to get you three easy yards through the air against a defense dead set on preventing three yards on the ground.

Also it’s not cheap to install. Getting those routes to mesh right takes a lot of practice that you’re not using on other concepts, and the more formations you run it out of the more you’re going to have to rep different timing.

Using up your tight ends on short routes also takes away your edge protection. As offenses like to use this to force one guy open you’re also sacrificing much hope of passing it to the pick player—the example above leaves Michigan with just two routes they can really throw to. Mesh teams therefore tend to see a lot of QB scrambles, since by covering the drag routes defenses tend to get soft around the edges. Noticed Michigan State’s running game is basically Lewerke escaping the pocket? A lot of that’s been on covered meshes.

-------------------------------------

WHY IS MICHIGAN USING A GOAL LINE?

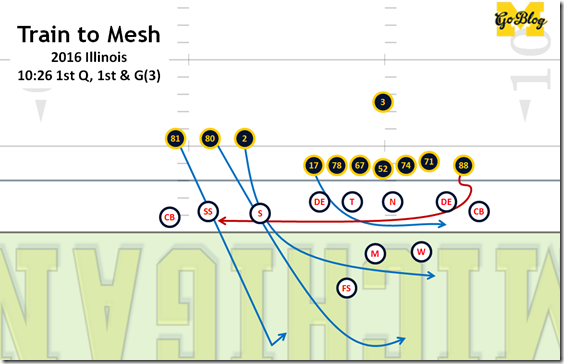

Because they’re running only three guys in routes, tight ends were the best jobs for those two routes, and everyone else is in blocking. We didn’t always run a 7-man protection on this, and you don’t have to. It’s virtually the same play they ran out of the TRAIN formation when it was first introduced, except Michigan exchanged two routes for two more blockers.

That’s a choice most coaches will make when running mesh with college players. More receivers means more opportunities to win a matchup and pop a guy open for the quarterback to find. More blockers means the quarterback has to worry less about getting sacked and doesn’t have to make as many reads, the tradeoff being the defense only has to win three routes to ruin the play.

Going into this season we kept saying Speight was going to win the job over Brandon Peters because Michigan was better off putting blocky-catchy guys like Hill, Bunting, McKeon, Gentry, Eubanks, and all the running backs into pass patterns, preferring such matchups to those guys versus their blocking assignments. Accessing that many routes however takes a quarterback who can read which are going to be favorable before the snap and finding those victories afterwards. What’s true for Peters is true for O’Korn, who while more experienced could not possibly be on the level Speight was playing at during the best part of last season.

So last year after the bye Michigan felt comfortable enough with their passing game to add some frippery and run this with a bunch of extra receivers. This year with the backup quarterback in they went super-simplified.

-------------------------------------

HOW DO YOU DEFEND THIS?

Depends on your scheme, but every scheme has a way. Practiced defenses (e.g. NFL ones) have complicated swaps they pull off whenever they’re getting picked, which makes it very hard to do that to them. But say your college defense hasn’t had the time with its DBs to get those down.

The first thing you can do is play zone, which basically turns mesh into Iowa’s offense. But say you’re not a zone team…

If you want to totally bone it, have your defensive ends bottle the crossers at the line of scrimmage so they can’t release until they’re way off schedule. Michigan by the way had a counter in case Purdue did that:

You’re looking on the right side of the gif where Wheatley is slanting out of his stance and #21 is just totally latched. That not only runs #21 out of the play but directs Wheatley directly into the MLB who’s supposed to be getting over to help. Even with Onwenu blocking nobody, the gap is massive and Evans has just one safety to shimmy past. But yeah, if Michigan had a Mesh on it was totally boned.

You can also defend this by executing your jobs well. If you’re in man, get in your guy’s hip pocket and then whatever space he’s running through you’re running through as well—like those assholes who follow fire trucks (looking at you, yellow Land Rover on Maple Road and Inkster at 8:54 this morning).

And you can do it with an awesome play. Watch how Dymonte Thomas (#25) and Delano Hill (#44) played this:

Both safeties have enough speed that they can afford to play off and close the distance once they’ve read the play. Thomas tracked it so well he’s there to stick for a “better punt that” zero-yard gain on 3rd and 3.

WHAT ELSE IS CALLED MESH?

The point in a zone read where the quarterback and the running back are both holding the ball waiting to see which should take it. That has nothing to do with this. Football terminology is dumb.

FURTHER READING

Most useful would be Inside the Pylon’s article and Glossary revisit. X&O Labs for coaches. More on Leach’s air raid variations from Cougcenter. Video by Bruce Ein. For something less air raid-y, check out TOC from before they went all icky. SC also wrote about a few variants before the 2015 season.