Re-watching Saturday’s game the damage didn’t look so bad—take away Cincy’s illegal picks and we’re down to quibbles about McCray’s position and Kinnel finally taking a bad angle that one time. There was only one play that Michigan didn’t seem to have an answer for, despite Cincy running it SEVEN times: The tunnel screens.

This is not a new problem; Maryland got 103 yards on four of them last year. Did Fickell find a hole in Don Brown’s attack? Was it a certain player? Was Cincy just good at that?

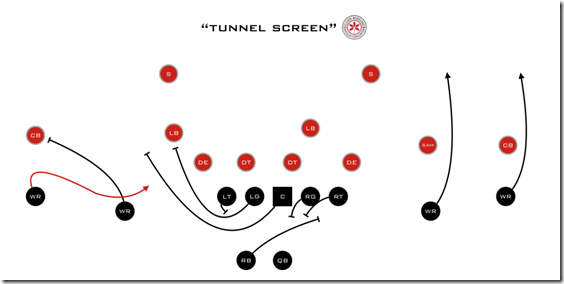

Quickly: WHAT IS: A TUNNEL SCREEN

Coincidentally I got this from Kyle Jones of 11W’s Cincinnati preview in 2014

A tunnel screen is kind of the reverse of a bubble: you block outside-in with a slot guy and bring your receiver inside-out. Typically covered linemen will seek to delay an insta-pass rush while uncovered OL release to cut off the second level.

It’s mostly a counter versus an aggressive man defense because you’re punishing linemen from running upfield so far you can squeeze a ballcarrier and his convoy behind them.

However in this game Cincy was doing some odd stuff with it. I’ve listed them by increasing order of weirdness:

1. Get the Ball to Your Athletes

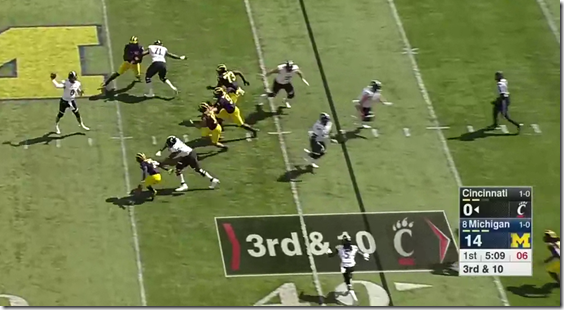

Like Maryland last year, Cincinnati came into this game with a plan to negate their offensive linemen and trust their athletes in space. Michigan for its part refused to back off the pass rushers, or to change up their simple man assignments for this game. Even on the 7th time they see this, Don Brown is not going to give any quarter inside to win a DT spy. He’d rather David Long wind up the Viper:

Bush did as well as you could ask to redirect with a TE cutting his legs out, but Cincy’s RB caught it in stride and accelerated quickly. Long on the other hand was way more hesitant in his turn at trying to woop the OL and ate a block. Kinnel arrived just in time to make this a 4th and 2.

Part of Michigan’s problem with these all day was the screen targets were very precise in their routes and excellent at accelerating with the catch. Running back Mike Boone (above) and slot receiver Kahlil Lewis were Cincy’s best offensive players, and this play was a good way to put them in a position to make that count.

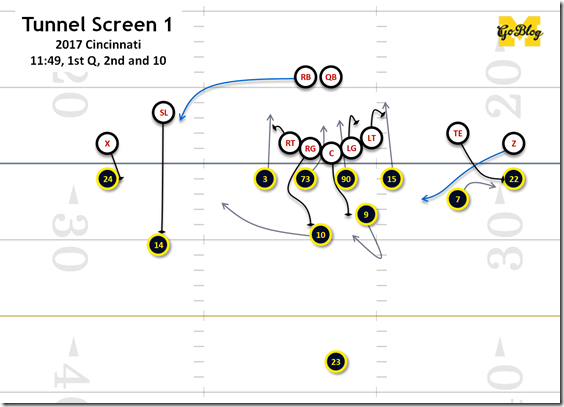

2. Tight End is Blocking a CB Off the Snap Like It’s a Run Play

Here’s the first tunnel screen against Michigan last week and you can watch the tight end motion across and make the key block on the CB (Long) in man coverage on the screen target (Michigan’s in straight-up Cover 1, with Hudson following the TE across rather than switching with Kinnel).

That gives Cincy a TE rather than a slot receiver removing the man in man-to-man coverage.

You’d like David Long to realize faster what’s happening and attack but that’s asking for him to make a big play.

By the way if you’re wondering if the TE can cut block while the ball is in the air, this is contact within a yard of the line of scrimmage and thus a legal block:

ARTICLE 8. b.Offensive pass interference is contact by a Team A player beyond the neutral zone that interferes with a Team B player during a legal forward pass play in which the forward pass crosses the neutral zone. It is the responsibility of the offensive player to avoid the opponents. It is not offensive pass interference (A.R. 7-3-8-IV, V, X, XV and XVI):

- When, after the snap, a Team A ineligible player immediately charges and contacts an opponent at a point not more than one yard beyond the neutral zone and maintains the contact for no more than three yards beyond the neutral zone.

The releasing center’s block on McCray wouldn’t be a legal block if he made contact with McCray, but he is just getting in the way and that too is legal.

Hudson is able to recover but now the receiver has momentum and gets 6 yards. Now that it was on tape Cincy eschewed the subterfuge and usually lined up the receiver directly behind the tight end in a stack.

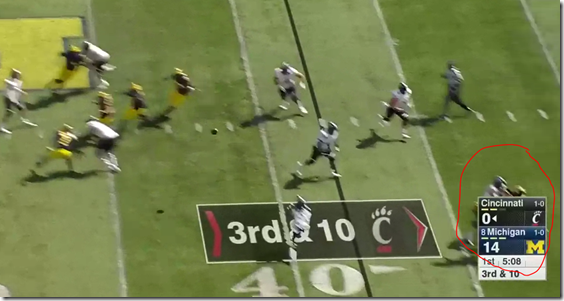

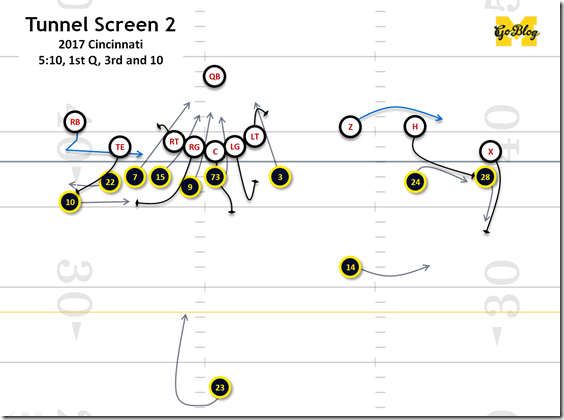

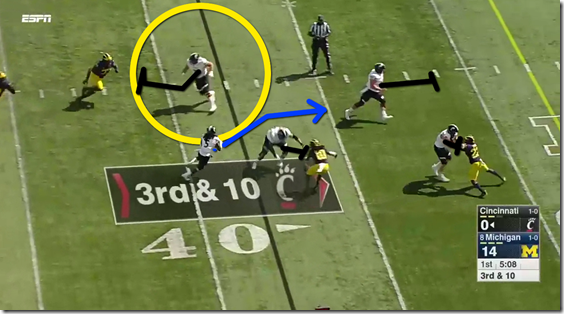

On the second tunnel screen (to the RB) they get Devin Bush playing off coverage, but the TE can still lock onto Long and take him for a ride.

I circled the TE’s block on Long this time because this play erroneously made the (mostly legit) list of missed offensive PI plays. But read that same rule above again:

ARTICLE 8. b.Offensive pass interference is contact by a Team A player beyond the neutral zone that interferes with a Team B player during a legal forward pass play in which the forward pass crosses the neutral zone. It is the responsibility of the offensive player to avoid the opponents. It is not offensive pass interference (A.R. 7-3-8-IV, V, X, XV and XVI):

The ball is caught behind the line of scrimmage, which the NCAA defines as a run for downfield blocking purposes. With Long blocked out by a TE it’s now all three interior OL escorting the RB downfield. Two of them are doing what you’d expect: the right guard authoritatively cuts out Devin Bush’s legs to make a lane, and the center is trundling downfield to take out Michigan’s last defender, Tyree Kinnel.

[After the jump: Seth loses his sanity, then we have five more of these]

3. Flare Option to the Backside

Very often a tunnel screen includes a flare option to the backside. Notice above that Bush, in man coverage on the RB, has to chase that away from the play. That’s key because if you can’t get that linebacker occupied with misdirection he’s hanging out right where this play attacks. If the LB lets him go you can just toss it out to the RB instead like so:

Sorry the beginning of this got clipped—the point is visible. Watch Hayden Moore on the rest of these as he quickly checks the other side to make sure someone is bothering to check the flare.

They can also swap jobs, using the RB as the tunnel target and a slot receiver as the flare:

This is the same concept from 5 wide. Putting the RB in the slot essentially flips the sides. The Z receiver on the left side is now running the RB flare, and the RB is the tunnel target. Metellus is now the dude they’re removing.

The QB watches Metellus go with the flare and comes back to the tunnel. With the RG ending Bush and a 5th man blitzing there’s nobody until Kinnel. Fortunately for Michigan Kinnel shot past the center and held this to just a 10-yard gain.

4. Didn’t Even Bother Blocking the DTs

It’s easy to say Cincy came in knowing that Michigan likes to get aggressive, and Don Brown got RPS’d:

That’s five defenders going hell for leather into the backfield and that never goes well versus a tunnel screen. But it’s also OL getting out really early, and that’s unusual. Typically the way a screen like this is blocked is you have the covered linemen chip/delay their guys while the uncovered linemen release. That buys your QB enough time to get the screen off.

Cincy had a different idea. The linemen let the DTs through and just block the ends, since those guys often have the speed to get to the QB before this can develop. To make sure this doesn’t end up with a VICIOUS SACK every time they had the quarterback drop waaaay back and just blocked the edges. Moore at least would know where the pressure’s coming from and get the pass off on a timer.

This was to negate a tactical advantage that the 3-3-5 provides and which helped nerf Florida’s attempts at the same:

See how slowly the Gators’ OL got out to block? That’s because the 3-3-5 (when run correctly) is really a 4-2-5, you just never know which LB is going to be the fourth lineman and where he’ll come. Not knowing delays the OL; by the time #65 gets out there, Bush has already inserted his face into the unorganized muck.

Now look up at the Cincy one and watch what happens to Hudson trying to do the same thing. The OL don’t waste time delaying Hurst and Gary. They just go, and are downfield fast enough to set up a vicious chop block on Hudson.

----------------------------

5. They had an Offensive Lineman Turning Around to Check Pursuit

I clipped the below from the second tunnel screen but I noticed it on every one of these, and I’ve never seen it before.

The first time I saw a guy do this I figured it was confused Cincy OL being themselves. The second time I wondered if they were coached to do that, and the third time I was sure.

And it makes sense: Usually a tunnel screen happens a bit beyond the line of scrimmage (why hang back any further than you have to?) But Cincy has backed up this whole operation. The quarterback is dropping way back so the interior DL can’t get home even without token resistance, the big kickout block is happening within a yard of the line of scrimmage, and the ball is being caught in the backfield. That could mean trouble if a defensive lineman smokes this quickly and doubles back. And you just saw Florida lose a couple of screen plays to Gary and Hurst running them down. And if you’re Cincy what would you rather have if you’re the offense:

- An extra (bad) OL who’s likely to get wooped by a Michigan safety, OR

- Insurance against All-American DT Mo Hurst reading the screen and putting your receiver in his belly?

What was Michigan’s Response?

A lot of vanilla, and switching up the viper. There are different ways to defend it but the best way to avoid eating five to eight yards on this is to have a DT smoke or spy—meaning he’s looking for the offense to try something like this and hanging out in the area. You’ll see a lot of teams do this with a Mone-sized nose tackle, since he’s unlikely to get upfield as quickly as Mone, let alone his friends.

That’s not how Brown does business—if you make him leave a DT at the line of scrimmage it’s probably some sort of zone blitz that brought eight. All the other plays in the playbook hated those aggressive DTs—what, are they gonna run this one all day?

Michigan did change up some personnel at times. On the above they decided to have Kinnel try to rush the edge faster since Gary and Winovich weren’t getting home, while leaving Furbush’s heft out at Viper. The plan all day was to have the inside linebacker take out the blocking while the Viper screams past his block and knocks this out. Furbush almost makes this play but the TE gets just enough (rubbin’s racing) of him that he only forces it back inside where there’s a mess from Bush eating a chop.

How are you SUPPOSED to beat it?

For one, whenever a defensive lineman meets zero resistance he’s got to react, stop, and retrace his steps. Michigan’s DL were emphatically not doing this against Cincinnati, as if they thought they could get to Moore in time to disrupt his pass. That happened once:

And on this one you can see Hurst reacting correctly to the running back and becoming a cover guy.

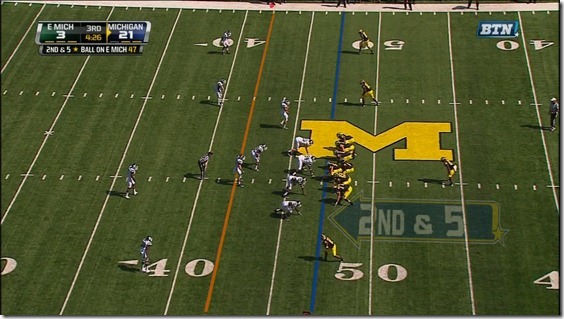

However Michigan saw these screens enough that you’d like to have seen something in the playbook to beat it. How do you rock this scissors? We learned this lesson the hard way: watching Brady Hoke call this early on with Denard under center. This is a play from the EMU 2011 game. Jeremy Gallon is at the bottom of the page. He’s going to run a tunnel screen. It ain’t gonna work. The kickout block (that Cincy was making with their TE) is going to be left tackle Taylor Lewan. Here’s the setup:

Look how far off that DB is. That’s playing super-soft. Also the DL are not going to be rushing pell-mell upfield because that’s how you eat a 46-yard Denard highlight. The carefulness results in a lot of defenders and Lewan standing alone on the 40 wishing for someone to block.

So yeah, the way to really kill this is to play super soft. Of course, remember what this is: a play designed for the offense to punish aggressiveness, so most of the answers are to not be super aggres—

er…I mean run a few more nasty zone blitzes out of that 3-3-5 we’ve barely scratched the surface on.