This series is a work-in-progress glossary of football concepts we tend to talk about in these pages. Previously:

Offensive concepts:RPOs, high-low, snag, covered/ineligible receivers, Duo, zone vs gap blocking, zone stretch,split zone,reach block, kickout block, wham block, Y banana play, TRAIN

Defensive concepts:Contain & lane integrity, force player, hybrid space player, no YOU’RE a 3-4!, scrape exchange, Tampa 2, Saban-style pattern-matching, match quarters, Dantonio’s quarters, Don Brown’s 4-DL packages and 3-DL packages, Bear

Special Teams: Spread punt vs NFL-style

------------------------------------------

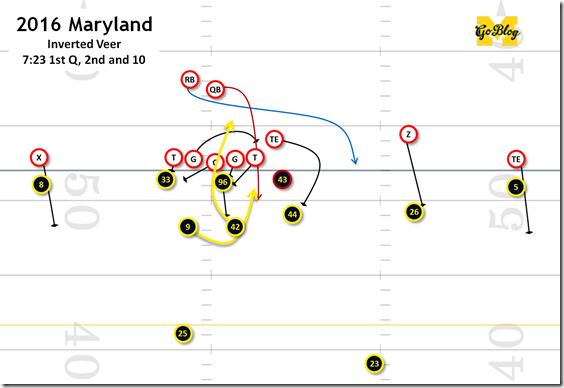

So today we’re going to get into a play that we’ve discussed a ton on this site: The Inverted Veer, also called a Power Read. From 2011-2013 it was the Michigan offense’s best play (even if Borges might have run it incorrectly). Since 2012 it’s also been the staple play of Ohio State’s offense. If you close your eyes and think of a collegiate Tim Tebow or Cam Newton or Cardale Jones play where they fake handoff to the running back before a QB plunged straight ahead for an unstoppable 6-8 yards, that was probably an Inverted Veer.

WHAT IS IT?

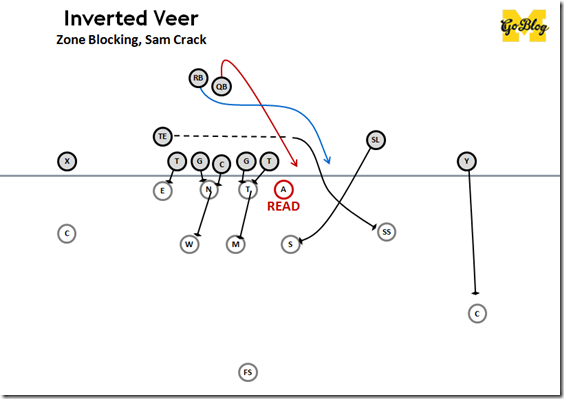

The best way to think of it is the reverse of the zone-read option. Whereas Rich Rodriguez’s option play was all about reading the backside edge defender, Inverted Veer is about optioning a frontside guy.

Basically the QB and RB will option a frontside EMLOS (end man on the line of scrimmage) by having the RB jetting outside while the QB reads the unblocked end and decides to give it to his buddy as he passes, or if the DE leaves enough space, charging downfield.

That’s it. I showed power on the diagram because that’s probably the best way to block it, but you can run this successfully with a variety of blocking so long as the DL are all secured on the backside. Major variations on it are whether you go inside or outside of the last DT you blocked, and how you want your TEs and receivers and whatever other material to execute various stalk blocks, kickouts and cracks.

It’s also a sort of personnel reversal from a zone read. On ZR the running back ends up reading his blocks and finding an interior gap, while a QB keep puts the quarterback out in space. With Inverted Veer the RB is the one threatening to edge the defense while the quarterback is charging headlong into it. That last bit is why it’s such a great play for all of those truckstick quarterbacks I mentioned: Once the defense converges that big QB will have a lot of downhill momentum.

Course a jitterbug with ridiculous change of direction is cool too.

[Hit the JUMP for some good ol’fashioned bedreaded one fun]

----------------------------------

HOW DOES IT WORK?

[EDIT: Fixed the names of old players I flubbed]

The idea is to option the frontside edge defender while blocking down on the rest and (usually) pulling a guard from the backside. In that way it’s a lot like a regular Power run. The big difference is the option:

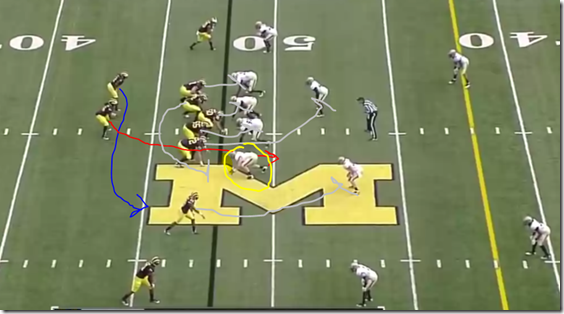

Denard is reading that guy, but the read is reversed from a zone read: If the DE sets up outside where he can run down Vincent Smith, Denard will keep. If that end shuffles inside to close the gap between himself and the right guard (Omameh), Denard should be giving the ball to Smith for an outside run.

Keep. Run correctly. it’s really tough to defend. Three OL have downblocks, a big advantage. And when the offense has a fast RB threatening the edge, the threat of his jet can really stretch that optioned defender wide.

The pulling guard is your ace in the hole: Here the slot receiver, Kelvin Grady, watched the SAM shoot up past where Grady could crack him. Grady smartly moved on to a safety, and when the left guard (Ricky Barnum) arrived from his pull he was able to redirect and seal the SAM outside of Denard’s lane.

Click for slo-mo on gfycat

The key block is that frontside defensive tackle (the 3-tech) versus the frontside guard:

Omameh had to fight hard to keep Purdue’s 3-tech DT (not Kawaan Short, who’s facing off with Molk) from getting free and tripping Denard up at the line of scrimmage. The quarterback, once he’s made his mind to keep, will often read that block and cut inside it if that’s going badly. Here they caught Purdue way undershifted, giving Omameh a good angle on the DT and opening up space to run up the frontside B gap. When you watch the slow motion, watch that block.

QUESTIONS

What’s a Veer? A veer play is any play where a ballcarrier (running back, wingback, receiver in jet motion, or even a quarterback) is getting the ball more or less from under center and jetting his ass toward the sideline in attempt to gain the edge. That’s as old as football, and threatening a veer by having a speedy wingback running that way after the snap was the basis of things like the Mad Magicians.

Option football became almost synonymous with the Veer in the Post War era because that was usually one of the options, the other options being runs like a dive (run straight ahead) or off-tackle. Your standard triple-option play, for example, was the fullback running a dive, the quarterback running off-tackle, and the running back running a veer, with one or two defenders put in a position to have to defend all three.

Teams that ran this all the time also let their QB read the safeties; if those guys got too aggressive the QB could stop in the middle of his rollout, form up, and throw downfield (yellow route). They also had inside (above) and outside (QB reads just the OLB and the fullback is running off-tackle) versions.

Run correctly it accounts for every defender with either an option or an easy block, and is indefensible. A modern triple-option team (2017 Michigan opponent Air Force) will have all of these options drilled so well that it still works most of the time. The downside is that’s a very long though chain for a college quarterback to screw up—there’s a reason it’s mostly service academies who run this these days.

Also, even teams that don’t use the option at all use a version of the veer with Jet motion, a concept we’ll get into another time.

Why “inverted”? What are you inverting?

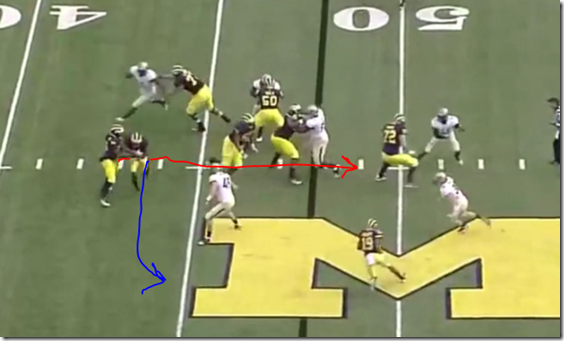

The line blocking. One of the reasons this play can be so devastating is you’re blocking defenders in a disadvantageous position. You can also mess with their keys. You’ll see teams that run this a lot will start psyching out the defense by starting off their double-team combos as if the run is going backside. That gets the DTs to try to fight that way too, freezing them inside and widening the gap. Watch the left tackle and the center right off the snap here:

That’s how you run between the tackles. The LT lined up outside but he led off by threatening a reach combo with the guard inside him, and wound up getting an inside seal when the DT fought way outside. The NT also reacted to the center stepping backside, got there first, and was locked there.

Who came up with this? Gus Malzahn gets credited until someone finds another example of an early spread guy tinkering with 1970s option football from a shotgun or pistol. Official origin doesn’t matter—what you should know is this is a modern shotgun adaptation of an old-ass football play that dominated the game in the 1960s and ’70s, especially in the old SWC.

Is it the same as “Power Read”?

Yes, that is Malzahn’s word for it. The thing about the Inverted Veer—and this is what starts arguments among football dudes all the time—is there’s a lot of things that it’s not that have become associated with it to such a degree, and one of those is Power Blocking, i.e. pulling a backside guard. However I find that misnomer because you’re running frontside you can use all of the blocking methods that frontside runs have ever used. You can certainly run it with zone blocking…

…and then if the QB keeps have him read gaps from the outside in. And you can also vary your pulls, for example folding the guard into the frontside A gap (if the 3-tech has been working outside), or pulling the backside tackle if the LBs are keying the guard.

But coaches who call it Power Read have a point in that the backside blocks are a lot like power blocking either way: the nose and backside end have to be blocked down, and then you may as well pull the extra lineman to the frontside and, like power, have him block whoever shows there. The nomenclature doesn’t matter that much.

Is it always a running back/quarterback exchange? No, because sometimes it’s a receiver. Ohio State in 2015 liked to bring out this unbalanced variant which put Ezekiel Elliott, a plus-plus lead blocker, into the blocking scheme, and made Curtis Samuel, the H-receiver, the veer threat, with Cardale Jones or JT Barrett threatening the inside run.

Also sometimes coaches will actually block the DE and not even read anybody, using the RB for jet motion to draw an unblocked SAM too far outside to stop a hard-charging QB from squeezing past. Usually that’s something they pull out when they just need to get a guaranteed 1 or 2 yards.

But Borges actually did that quite often, either because he didn’t trust option football, or he just decided the quarterbacks Rodriguez left him were better at making a totally unblocked guy miss than making an option read. It worked at least:

----------------------------------

DEFENDING IT

I like showing examples of how to beat offensive concepts, but remember these are just samples. Basically I want to give you a taste for how a sound defense can stop anything by everyone executing their assignments, how a defensive coordinator can scheme to shut something down, and how a great individual play can also do the trick.

Option A: Read your keys/execute your assignment

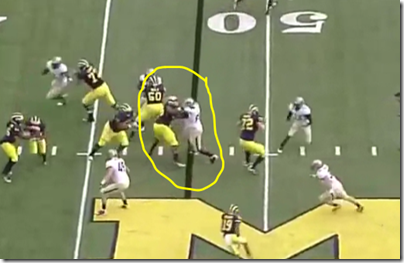

The DE getting optioned here is Taco Charlton while the guard coming across is meant to pull around and hit a linebacker. But Taco read that he wasn’t getting blocked and shuffled down the line and set up tight to it in the backfield. This should at least force the quarterback to hand it off. It gets a 2-for-1 because where Taco set up is right in the way of the pulling guard. Taco and McCray have been coached to react this way (Don Brown’s BC playbook has a page on this): if Taco is coming in, McCray knows he has to get wide to set the edge of the defense. He does this, dutifully following the RB outside. Gedeon, the backside LB on this play, read the pulling guard just in case the QB kept it. McCray strings that to the sideline for no gain, with Gedeon chasing to make sure there’s no cutback.

Compare that to a few plays earlier when McCray didn’t get wide:

Here’s both of those plays right after the handoff and I don’t think I even have to tell you which one McCray stopped for a loss and which went for 8 yards:

Read your keys.

Option B: Solve your problem with aggression

This was some dirty anti-run blitzing by Dirty Donny Brown. Don Brown likes to use a 3-3-5 against teams that run a lot of Inverted Veer because it disguises assignments from the blockers who need to execute them. On this one he ran a twist blitz with McCray and Gedeon, getting Gedeon in right on the heels of the pulling guard, i.e. right where the quarterback is supposed to be.

The center probably should have looked for a linebacker after he saw McCray shoot playside, but even if he had and took a step back to block Gedeon, that puts him in the path of the puller, and McCray is already shooting right into the gap they’re attacking.

The pulling guard would get to the hole two steps behind the LB, McCray, he’s expecting to erase; he can only dive at McCray’s feet, and misses. Wormley sets up outside against the RB and by the time the QB decides he has to keep and try to cut into McCray, Gedeon appears unblocked in the backfield.

Mattison had something like this in 2011 by the way.

Option C: Linebackers kick some ass

I remembered a play from MSU that I had in mind to use for this because I was certain it would be an example of Peppers shooting past blockers to destroy an edge play, since that’s what he was doing all year. But Peppers wasn’t the only linebacker to win this play by winning a 1-on-1 battle. Check out Gedeon:

Again Michigan was defending this by having the DE step down on the line and force a give to the RB. Peppers indeed shot past the attempted block by MSU’s tight end, Josiah Price, and could have blown it up that way, but Price got a last-second arm on Pepper’s shoulder. That might not be a legal block (judges?) but either way it was just enough to throw off Peppers’s trajectory and get LJ Scott outside.

But Gedeon did the same thing. The inline TE, Jamal Lyles, is supposed to wall him off, but Gedeon read the play and exploded past. Once he saw Peppers going inside, Gedeon widened to defend the edge and chased LJ Scott to the sideline, with an assist at the finish from Jourdan Lewis. Once again, great players can stop pretty much anything.

----------------------------------

Further reading: Brian picture-paged this after OSU 2011. He also picture-paged MSU blowing it up in 2012 when Borges was running it without optioning anybody. I did a Neck Sharpies last October on how Don Brown likes to play it. Afore-linked Picture Pages of Mattison blowing it up vs Purdue in 2011.