Derrick Walton has stepped up in the latter half of B1G play [Bryan Fuller]

If you’re looking for Ace’s preview of tomorrow’s contest against Purdue, it’s linked here.

As an addendum to that, here’s how dominant Boilermaker big man and probable All-American Caleb Swanigan is on the glass:

Fortunately Michigan is indifferent to the offensive glass so Swanigan’s dominance in preventing second-chance opportunities isn’t quite as significant; still, he’s a phenomenal rebounder even though he’s not much of an above the rim player. His strength, positioning, and ability to go get the ball (even without a great vertical leap) is impressive to watch.

Swanigan’s player comparisons are pretty insane as well:

Swanigan is a Jared Sullinger who’s 30 pounds lighter, can pass the ball extremely well, and shoots 47% from three. Needless to say, Michigan needs DJ Wilson (and Moritz Wagner, probably) to somehow neutralize him – the Purdue big man is a much more physical player, so staying out of foul trouble is a major key.

Anyways, there are some graphs of Michigan’s scoring and efficiency trends after the JUMP:

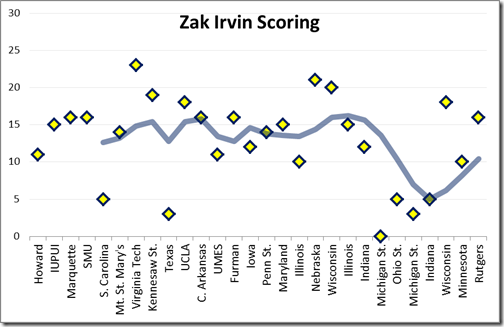

Lines are 5-game running averages

Michigan is a team with very little depth: eight players play rotation minutes and two – Xavier Simpson and Mark Donnal – are mostly invisible on offense and typically don’t play significant minutes unless there’s foul trouble of some kind. There are six players who collectively produce Michigan’s scoring output, and there’s quite a bit of balance between them.

Here are the scoring averages for those six players:

- Derrick Walton: 14.3 points per game

- Zak Irvin: 12.8 points per game

- Moritz Wagner: 12.2 points per game

- DJ Wilson: 10.4 points per game

- Muhammad-Ali Abdur-Rahkman: 8.9 points per game

- Duncan Robinson: 8.1 points per game

Until Walton’s recent run of excellent form, Michigan never had a player who’d go for more than 17 points per game over a 5-game stretch. This balance is a strength in some ways – as a poor performance or two from among the six key contributors isn’t catastrophic – but the Wolverines’ lack of a go-to guy has been a well-documented concern. Hopefully Walton can be that clear first option as the season draws to a close.

The two most interesting scoring trends are from Michigan’s two senior leaders, Derrick Walton and Zak Irvin. Our slack thread put it well:

Irvin scored in double digits in 19 of his first 21 games – aside from notable clunkers against South Carolina (in which the whole team shot poorly) and Texas (the ugliest game Michigan will have played all season), he was the mark of consistency in terms of scoring output. As the least efficient member of Michigan’s six-man core, it sometimes took too many shots for him to get those points, but Irvin was a stable source of points for most of the season.

He seems to have recovered from the huge dip in production after putting up 18 and 16 points in wins against Wisconsin and Rutgers, but that slide was severe: over four games, Irvin scored 13 points on 33 shot equivalents – amazingly poor numbers. Fortunately for Michigan, Derrick Walton’s emergence as a strong scorer helped mitigate the damage and the Wolverines somehow went 2-2 in those games.

While he’s come to earth recently, Walton’s February surge will likely have been the deciding factor in getting Michigan into the NCAA Tournament (if they make it). In five of the seven games immediately following the “white collar” comment, Walton scored at least 20 points. Even though he fell off quite a bit against Wisconsin in terms of scoring, he still added eight assists in arguably Michigan’s biggest game of the season. At this point, it’s hard to argue that he isn’t the best player on the team.

* * *

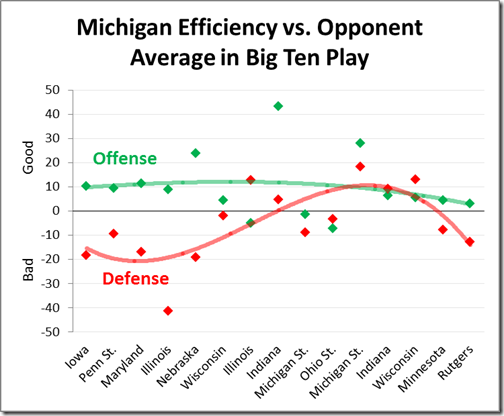

Data points are (Offensive Efficiency – Opponent Average Defensive Efficiency in B1G Games) and (Opponent Average Offensive Efficiency in B1G Games – Defensive Efficiency) for the given games. The lines are 3rd-degree polynomial trends.

Michigan is a team of extremes: their offense is the best in the Big Ten and their defense is the third-worst in the conference. Early on in conference play especially, the Wolverines struggled to get stops and lost four of their first six league games, allowing more points per possession than their opponents’ averages in each of those contests. They had five of their six worst performances to open conference play. An unsustainably high opponent 3-point rate was a big part of that, but it was abundantly clear that the Wolverines needed plenty of work on that end.

Since the Nebraska game, the defense has been mostly solid – though the two most recent games against Minnesota and Rutgers are troubling. The Wolverines undeniably improved on the defensive end in the middle third of conference play, even to the point where they were playing above-average defense for a Big Ten team for a little while. In the critical three-game winning streak of Michigan State, @ Indiana, and Wisconsin, Michigan had a better defensive performance than they did on offense in two of the three wins.

Michigan still allows the worst opponent eFG% in the league by a wide margin, though they’re average or slightly better in each of the other four factors on that side of the floor (turnover %, defensive rebounding %, and opponent free throw rate). Assuming that the Minnesota and Rutgers games aren’t the start of a worrying slide – and considering that they only gave up 1.11 and 1.01 points per possession in those games, it’s not too alarming – it’s possible to conclude that the defense really has significantly improved for the Wolverines.

The offense has been remarkably consistent throughout conference play, as Michigan scored fewer points per possession relative to their opponent average just three times in fifteen games. Aside from especially strong performances at home against Nebraska, Indiana, and Michigan State, they’ve been between about 0.10 points per possession better or 0.05 points per possession worse than their opponent averages – on aggregate, good enough to be the conference’s best offense. Avoiding any truly bad offensive performances has been key with an iffy defense.