A few years ago it was de rigueur on this site to talk about how college rules allowed NCAA teams to use a different style of punting, and that this style (called spread or shield) of punting was demonstrably superior to NFL-style (tornado). Michigan has swung between them in recent years. Carr tested out something like shield punting in 2003 then scrapped it when it cost him a game against Iowa. Rodriguez took us to spread punting along with spread offense, and Hoke returned the program to pro-style as was his wont.

In 2015 Harbaugh brought in special teams guru John Baxter and the spread was once again installed, presumably for good. Then Baxter left, and this year Michigan used both. At first we wondered if this was, like under Hoke, some relic of a coaching staff that strove to be pro-like in everything. But as the punt blocks, and near punt blocks, and running-intos that by all rights should have been punt blocks piled up, a new thought emerged: maybe Michigan thinks they’ve solved the spread punt.

Shield punting refresher

For a full explanation of spread punting and a comparison to NFL-style see my 2014 article or watch the Joe Daniel Youtube. Here’s a graphic:

The splits are huge: two yards between the snapper and the guards, and two more yards until the next guy. You don’t care who comes up the A gaps—the only thing the guys on the line of scrimmage have to do is redirect the man lined up outside of them then get downfield (you don’t want your snapper involved in blocking).

The three guys standing about 7 yards back are the “shield”. You want big burly dudes for your shield, and you tell them the Grand Canyon is just behind their heels so they’d better not give an inch. By not giving an inch, they create an eye in the middle of the storm for the punter to safely get the punt off.

Everyone else just has to force the attackers to widen to the point where they can’t get back inside in time to affect the punt. That’s why the guards split so far apart: anyone going outside of them should presumably be too far outside to affect the punt. Anyone coming up the middle will get stuck behind an immovable wall of beef.

In the linked video, Daniel mentions the way to attack it is put four guys into those big “A” gaps, because that could overwhelm the shield. The way the shield would deal with this is block out man-to-man, and let the guys in the A gaps try to get around the shield. As long as your three-man shield can still stop four A-gap rushers, you’ve got a sound punt blocking strategy with two to four more guys releasing downfield than you would in an NFL-style punt.

So…

[After the JUMP we get around the shield]

Here’s what Michigan was doing:

Disclaimer: I’ve never coached special teams so I’m just a dude watching football in slo-mo until I think I’ve figured it out. Coaches’ opinions are welcome. Anyway what I think Michigan has been doing is putting the guards in a damned-if-you-do/don’t situation.

Remember the guard tactics: spread wide enough so that if you kick out the guy lined up outside of you he’ll never get to the QB, and let everyone else get blocked by the shield. Now, if A-gap guys are getting around the tackles, shield punt teams have to adjust, and the most common adjustment to that is to have the guards block down instead of out.

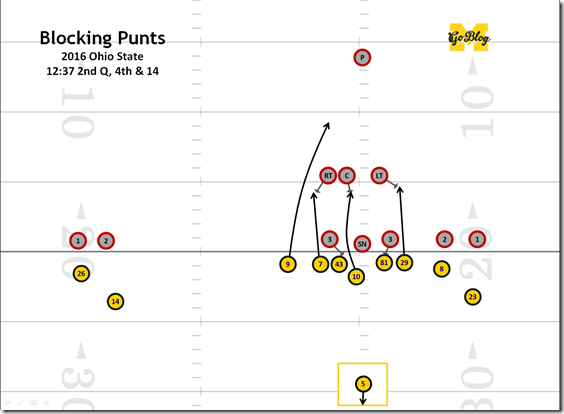

Michigan’s strategy, I think, was to line up two fast attackers—safeties or receivers—to either side of those guards, and make the punt protection wrong no matter which guy they block at the line. If he kicks out (standard) there’s a quick, agile player with a straight line to the outer edge of the tackle, which is a problem. If the guard blocks down (adjustment), the guy lined up just outside of him wasn’t kicked, and also has a super-quick route to the tackle’s outside. This results in four attackers hitting the shield in all four of its gaps:

Michigan has two fast/athletic guys lined up over each guard: Khaleke Hudson, Drake Harris, Tyree Kinnel, and Jordan Glasgow. Inside they’re bringing Devin Bush, who’s there to thwack the wall backwards, and Michael Jocz, who is super tall.

The guards decide they have to block down, and the guys getting blocked (Kinnel and Harris) duly take their blockers in man-to-man. This leaves Jordan Glasgow and Khaleke Hudson, who have just 2 or 3 yards of horizontal to make up with nobody kicking them out, coming at the flanks of the shield. And the shield can’t break out and get those guys because there’s two dudes coming into either gap between them.

Michigan’s attackers are playing option: if the guy across from you blocks you, he’s yours, and if he doesn’t you get upfield. No wasted guys.

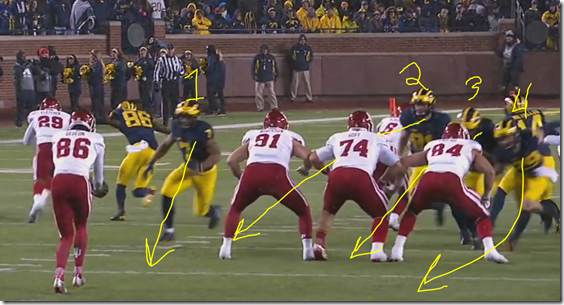

Even when four guys don’t get to the shield this can create a block. Earlier in the Indiana game the #2 gunner on the (receiving team’s) right got Hudson’s shoulderpads and tackled him, effectively blocking Chesson from getting upfield:

But the three attackers who did get through were able to isolate one of the blockers by attacking gaps to either side of him.

On this one Glasgow (top) forced the punter to alter his trajectory inside, where the long arm of Jocz was able to extend a hand into its flight path.

Adjusting to Michigan’s attack

Ohio State had an interesting solution to making the center of the shield relevant again: they moved one of the shield players to the outside, creating another lane so that the punt blockers couldn’t double up every guy on the line.

Unfortunately Michigan’s first attempt at it they were missing a player:

10-man punt team woo

But notice the two-man shield. The third guy has come down to the right near #5. Ohio State was adjusting the shield to widen the path of Michigan’s attackers, moving strength from the middle where it wasn’t as needed.

Here’s their second punt (this time against 11).

The spread punt is now once again working like it’s supposed to, with Grant Perry’s path to the punter too wide to cause any harm—Perry (far right) would wind up stuck behind Khaleke Hudson (second from right).

The right tackle (who’s more of a linebacker/fullback type) will point out the guy he’s not blocking and set up to route Hudson outside. Knowing where the pressure’s coming, Johnston can stay on his hash and get the punt off before it arrives.

By having the two guards (#3 gunners) block down on the inside guys there’s only one blocker needed to stop the middle rush, and only one middle rusher, Devin Bush) to worry about.

This adjustment isn’t without potential consequences. What Ohio State has done is essentially hybridized the spread punt with the old fashioned NFL or “tornado” punt, which uses blocking types at the line of scrimmage and a few H-backs with blocking ability and agility to fend off the outside rushers. With that hybridization returns some of the weaknesses of tornado punts, namely less athletic #3 gunners, less beef in the shield, and a much greater risk of blocks because attackers are one-on-one with their blockers in space.

Cameron Johnston is one of the fastest punters I’ve ever seen at getting rid of the ball, and yet Hudson was inches from getting a hand on this one.

And on the first punt, even with Michigan putting just 10 guys on the field, the “center” (#48) had to commit a flagrant, full-jersey-extension hold to prevent Hudson from getting to Johnston.

Michigan should continue to recruit the kinds of athletes who can win these super-quick battles, putting opponents in a tough position of keeping more blockers back (creating more room for returns) or hoping the inevitable roughing and running-into-the-kicker penalties will offset the blocks.

Video of OSU’s punts:

Ohio State also rolled the blocking to one side, because Cameron Johnston is the consummate Aussie who can do that sort of thing. Michigan tried to counter by stacking one side or the other and Ohio State had planned for that too, with a fake punt run to whatever side was just abandoned.

Fortunately Jordan Glasgow was having none of it.

Anyway most opponents aren’t going to have access to they kinds of athletes Ohio State has in droves. Cam Johnston is the Peppers of punting, and instead of 300-pound tackles the Buckeyes can put a guy like Sam Hubbard in the shield. So ultimately like any other football play, what Michigan is doing against spread punting is finding ways to showcase super talent, and Ohio State’s response is the same.