We were cheering so much when they brought out the train that we missed how cool the play design was that they ran with it. It’s not the most complicated play to break down, but it’s certainly the most fun I’ve had breaking one down.

All aboard:

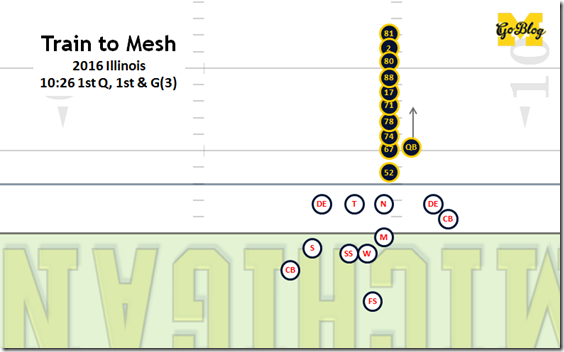

The Train

Other than looking cool, the train formation does actually accomplish something. The defense is trying to figure out who’s got whom, but can’t actually line up and sort out the offense’s look until this weird huddle has broken. It’s hard to catch numbers with all those other dudes in the way. It might not even dawn on the defenders until the snap that all the skill position players are tight ends (or in the case of Hill, a quasi-TE turned fullback). The train doubles as a huddle—Speight walks up the line giving the playcall—but preserves a no-huddle offense’s confusion factor.

If you’re an opponent, you don’t have a lot of time to dissect the various shades of blocky-catchy. And down near the goal line you’re not going to have the luxury of playing cover 2, since any underneath dumpoff is a touchdown. With a weird formation, the simplest thing to do is call a man defense, and everybody line up in their spots.

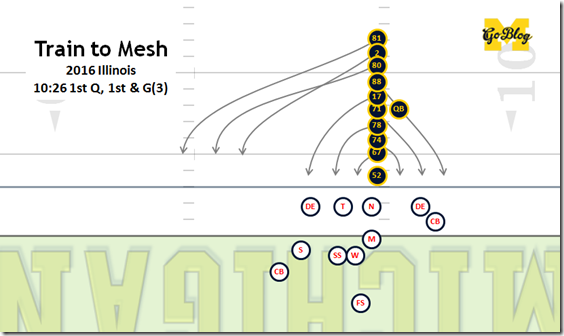

Then Speight claps his hands to break the huddle, and everybody rushes to his spot.

[After the Jump: Why five tight ends, why mesh, and how the rule that spread teams proved unfair is also unfair for teams that run out lots of TEs and crossing routes]

The Five Tight Ends

Why tight ends? Other than tight ends love to hear there’s a program that runs a 5TE set, Harbaugh has a good reason: they’re wild cards. The train thing makes it hard but not too hard to figure out who’s who, but if they’re all tight ends it’s impossible to know who’s what. They could come out in a super-heavy formation and blast their way into the end zone, or in a five-receiver spread, or anything in between.

This formation is a trips 2TE, except with the three most blocky guys acting as receivers. You don’t see trips 2TE very often even against spread to pass teams. You see it in Hail Mary situations.

Again, it’s about confusion. The defense is thinking about matchups going badly as cornerbacks and linebackers and whatnot are matched against tight ends with varying degrees of blocking or catching skill. They’re trying to figure out what it all means. And the ball is snapped before they’re really sure. A thinking defender is not a reacting defender.

And getting the right matchup can make a play. Jake Butt versus a tiny cornerback or a linebacker who’s weak in coverage is an instant #Buttzone TD. Devin Asiasi blocking a defensive back could get your defender blown down into the other defenders’ paths to the ball. Pull the beef out of middle and you’ve got 200-pound dudes trying to stop a hammering panda. Hybrid players let you put odd skills in odd places. Of course they still have to execute with those odd skills to get a win from that.

This time the matchups were mostly for show. Wheatley ends up blocking a cornerback—that was fun—and Butt winds up in a footrace with a coverage-y linebacker, but that’s nothing you wouldn’t get if Michigan put three actual receiver-type things in the trips formation. Burly receivers.

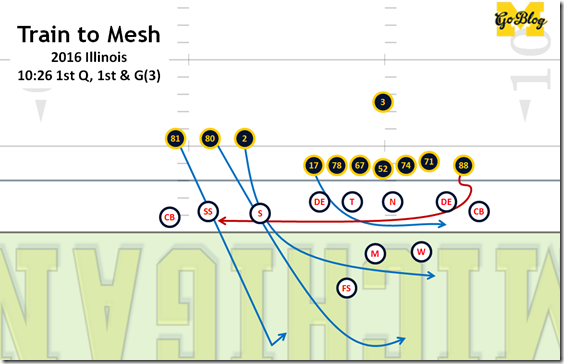

The Mesh

And this play needs some quick reactions to stop. Mesh is the classic man-beater. The receivers run drag routes across each other, presumably with their man-to-man coverage trailing behind them. At the crossing point, the receivers pass, the coverage gets caught in the wash, and somebody’s open.

This close to the goal line they can also take advantage of college football’s extremely kind three-yard downfield blocking rule. After three yards from the line of scrimmage if you block a guy on a pass play it’s (supposed to be) pass interference. But inside three yards it’s blocking, even if the only point of the block is to interfere with a guy in pass coverage. In his Colorado FFFF Ace caught them running a “drag screen,” dispensing with the pretense of receivers passing each other and just having one guy block the man covering the other guy:

Wisconsin ran it against us too—on one Stribling managed to fight through the mesh and break it up; on the second a Wisconsin TE made a block five yards downfield, it wasn’t called, and Jazz Peavey got a 14 yard gain. Michigan downloaded it too:

Wheatley (turquoise route) is lined up on the trips side and will blockpick accidentally run into the cornerback who’s covering Butt (red route) coming the other way. The other three tight ends are coming inside to draw their defenders away from Butt.

If they do catch zone, those routes should find holes between them as the inside routes become a flood concept. Wheatley is down low, Asiasi is attacking the level between the LBs and safeties, Hill is crossing in the back of the end zone, and Jocz’s job is to find a spot to sit behind anything that gets run off by Hill and Butt. If they catch a blitz, Asiasi or Jocz’s routes are “hot”, i.e. they’re running basically slants and looking back for the ball (if neither’s open the ball gets thrown out of the endzone).

Is There a Way to Defend This?

The defense’s best hope, other than playing a game of chance with zone or blitzing, is to tie up the mesh receivers at the snap. If their routes are delayed, the mesh won’t happen at the right spot, and the pass rush has more time to get home against a five-man protection. If you can jam either drag guy on his release, it can put him off his route, creating space for defenders to slip between the mesh.

Illinois did try that here; they just failed, in part because the TEs ran good routes, and in part because the Wheatley assignment isn’t as reactive to timing—he’s blocking the cornerback on Butt, not trying to rub him off and get open at a specific spot. Here are the respective releases:

BUTT | WHEATLEY |

|  |

Michigan gave Butt some extra space by having him align in a bit of a Flex position, i.e. a couple of yards off the edge of the line. Butt’s first step was wide outside and he sold it so well the cornerback froze. The next step used that plant to jet inside and create the crucial cushion.

Wheatley had to deal with the SDE providing a chip before getting into his pass rush—that’s usual for a defensive end with a tight end releasing into him. Wheatley creates space to get into his route by getting off the line of scrimmage quickly, getting his arms across the shoulder of that DE, and using his size to bounce off without getting knocked into the wash or onto the ground.

Butt’s release was that of a good wide receiver; Wheatley’s was a great example of why size and hand development are important for effective tight ends. It’s questionable whether either would have been as good at executing the other guy’s release.

Behind Wheatley you can see the Illini linebackers (illinibackers?) Asiasi’s route crucially kept the SAM lined up over there inside. Even in Man 1, the linebackers will be playing short zones. As you can see the linebacker over Asiasi got his arm out to route Asiasi inside—if he gets behind the LBs then he’ll get open or get another guy open, but as long as he’s in front of the LB level he can be passed off. A good LB will route Asiasi inside, step down in his pocket until he gets to the next LB’s zone, then fire out to next threat.

Asiasi himself got an arm out and muscled the SLB back some. In the 2nd square below the SLB should see Butt coming across and let Asiasi take himself to the MLB. Instead he got caught up handfighting to prevent Asiasi from getting depth on his route, and didn’t react to Butt coming until way too late:

It’s still Butt versus a linebacker in acres, but it’s wide open because illinibackers.