Okay so I’ve talked about this before. Maybe more than once. But Ohio State loves this play, so much that its variations account for 3 of the first 4 plays on Curtis Samuel’s Oklahoma highlight reel (and 2 more are counters off it).

Inverted Veer (again)

This play is called “Inverted Veer” or “Power Read.” It was the staple of the Borges-Denard/Devin fusion cuisine era, because it is the mullet of offensive plays: manball business in the front, spread party in the backfield.

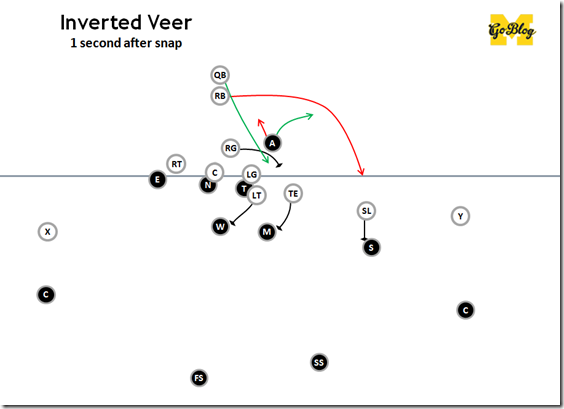

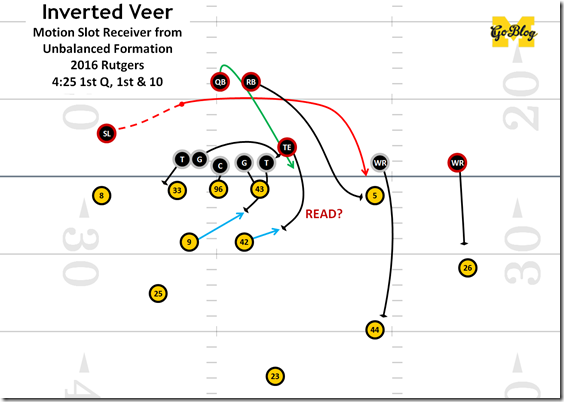

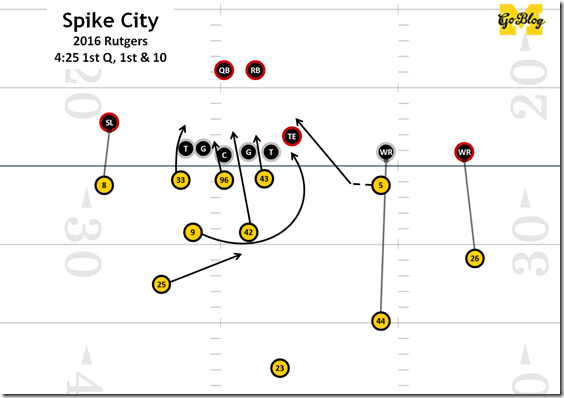

Here’s a basic setup:

The offensive line is blocking like power C: block down and pull from the backside, and cave the frontside.

A second after the snap reveals why it’s such a devastating play:

While a good ol’fashioned zone-read might option a backside defender, inverted veer options the playside end man on the line of scrimmage (EMLOS). That defender is allowed into the backfield and optioned: if he comes up too far, the ball is given to the running back, who accelerates away to the outside—You’ve been EDGED! If the end gets wide to prevent the running back from getting the edge, that opens up room for the quarterback to dive into the gap behind him—You’ve been GASHED!

[Hit THE JUMP for variations, and how Michigan defended this]

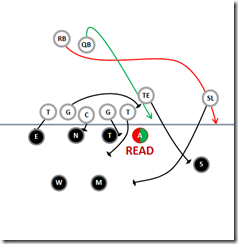

The rest of the blocks are supposed to be guys in advantageous positions. The only iffy matchup there is the slot receiver versus an overhang defender, and offenses have a bunch of ways of dealing with that. Like have him crack the MLB while the tight end kicks the SAM (left-below), or replace him with a lead-blocking fullback (right-below)

If your back is a heavier, North-South type and your jitterbug slot receiver is your best offensive weapon in space, try the ever-popular jet sweep version:

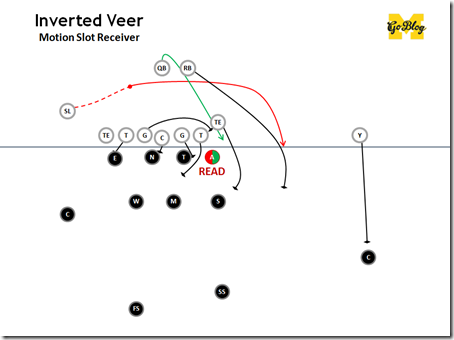

…and maybe make than an unbalanced formation to steal an extra blocker:

That’s what Rutgers did. Then something happened they did not expect.

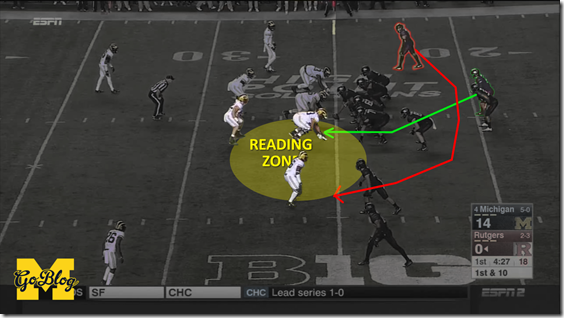

So Michigan is in one of Don Brown’s “50” fronts:

Specifically, it’s the favorite “Pup” 3-3-5 look that dominates the 3-4’ish parts of the playbook. From the Don Brown Glossary I wrote last summer:

Pup is basically the flipside of Bandit, and it's all over the playbook, with the Pup often blitzing. Seriously, most of the last third of the playbook is just nefarious Pup blitzes, including one where he's standing around in the middle of the field making noises like he has no idea what's going on, then right before the snap he creeps right down the center and blitzes an A gap.

And that makes sense since you've taken what's normally your top pass rusher off the field for the Pup, and nobody likes a quarterback standing around all bowels intact-y. If Bandit is the 3-3-5, the Pup formations are really a 3-4 that has traded in some of the weakside OLB's pass rushing for more ways to confuse the protection.

Except Peppers isn’t the Pup like in the glossary diagram; he’s playing the SAM role, and by that we mean a Jake Ryan/Clint Copenhaver quasi-DE SAM.

At least I think Kinnel is back there somewhere—only 10 Michigan defenders actually appear in the video; either way they wrecked this with only that many.

The Reading Zone

The reason Rodriguez named his option the ZONE-read is because you’re not actually reading a player—that could be too easy to mess with for a defense. Rather, you’re reading a zone, just like in pass principles. As with passing zones, the point is to threaten both sides of where a player should have to cover, and attack the one he leaves most open. So the zone in play here is the area at the end of the line of scrimmage. And the guy being read is whoever among defenders draws that duty. Also like with passing into zone coverage, if you read it incorrectly, or the zoned guy can cover so much space it overlaps with the next defender, there’s nowhere to go.

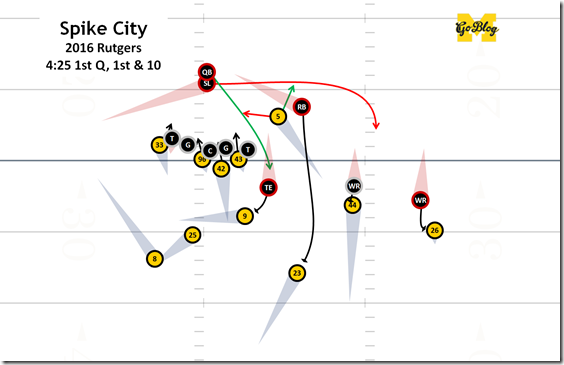

On this play there are three relevant defenders lined up around the zone who might be the playside EMLOS.

Wormley is the strongside end, but he’s lined up inside the left tackle, so unless he’s slanting hard outside, he’s not a good candidate to read—after all if he is responsible for the lane outside the tight end he’s got two offensive players at least to shoot past.

Gedeon is a more likely target. He’s lined up a little outside of Wormley, off the left tackle’s shoulder. And then outside is Peppers, but he’s all the way on the hash, and isn’t that guy a nickelback or something?

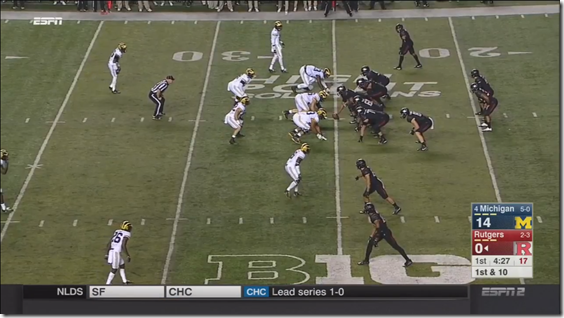

One key that Rutgers missed here is that both Peppers and Delano Hill are lined up over the covered receiver. Covered or not, two defenders over the same player is almost always a sign that the first guy is blitzing. Sure enough, Peppers starts to motion inside just before the snap.

In the second frame above you can see the tight end saw what Peppers is doing and is pointing. The TE at that point decides he’s going to block Gedeon since Peppers is standing in the option zone and leaning like he’s coming.

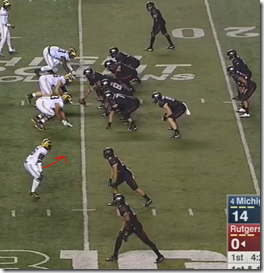

But nobody in the backfield appears to hear it—the RB and QB are both playing this like a inside linebacker will be optioned. The running back will still try to block Peppers, and the quarterback keeps his read eyes on the linebackers, flipping to McCray when he and Gedeon cross.

Now it’s time to make the decision: keep and try to run behind McCray before he can recover, or give and hope the jitterbug can beat a WLB to the corner. That seems like the better option.

Except the QB didn’t read Peppers, allowing Michigan’s Thorpe-like object to foray deep into the backfield, right where you don’t want him to be. The RB can still try to block here—maybe get a chip or something—but any block this close to the running play is gumming up the works. Maaaybe if that’s a old fashioned, neck-rolled SAM, and you’ve got Curtis Samuel you can get away with that. But this the best player in the country. He gets a whoop.

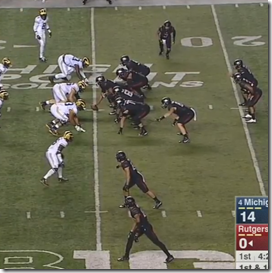

Whoop.

In Soviet Defense, EMLOS Options YOU

Here’s Michigan’s play. Hill is nominally in man on that receiver but thunders up at the snap since his man isn’t eligible—Delano is playing the hybrid Peppers role while Peppers moonlights as Jake Ryan. Dymonte Thomas went a step further: he’s the “rat” covering a zone and a gap you’d normally have a linebacker handle. McCray swung to the strong side to become the de facto MLB.

“City” is the base Cover 1, but they’re doing it with lighter personnel. Like you’ve got a free safety, Dymonte Thomas, covering an easily attackable backside B gap, and Gedeon substituting acceleration for mass to handle an A gap, and of course, Peppers taking the role that Wormley or Rashan Gary would normally have. That is disadvantageous if he ends up meeting a guard in close quarters, but very advantageous if he ends up in enough space to dodge a block and recover—or has to cover two sides of a zone read.

The Gedeon blitz won an extra man when the tight end went after the wrong linebacker, leaving McCray a free hitter. That is just Peppers formed up, saw the RB trying to stalk block him, and whooped a hapless RB. That’s how you get two defenders swallowing the ballcarrier two yards in the backfield; either one

But let’s assume for a moment that Rutgers ran the play correctly, since you know Ohio State will. This defense is still set up well to defend that.

I don’t know if those trails (from start position) are confusing or helpful. Anyway if the defense does suss out what the defense is doing, they’re still having to option Peppers. Their best case scenario is to try to block him anyway with the RB like they did, and give up on the outside; a QB keeper if the TE can seal McCray puts the quarterback in a 1-on-1 with the deep safety.

Of course that means the offense has to see and react to all of this in real time, with players moving around all over the board. And by the time you’ve done so the play is forced inside and subject to a running back vs Peppers block in the backfield. How many offensive coordinators would take that?

It’s very Don Brown. Rather than have a defensive end attacking the formation’s strength with brute force, he’s got a slippery speed weasel lined up in space. He can come off that edge so fast that pass protecting against it is a nightmare. In the run game he’s hard to get a body on, and so athletic from a formed-up position that he’s capable of playing both sides of an option, or delaying that for so long that reinforcements arrive.