Watch the receiver at the bottom of the screen

We’re going to be talking more often in the next few weeks about Run-Pass Option (RPO) plays, also known as packaged plays. Rutgers lives off them, Indiana loves them, Maryland is installing them, and Ohio State has made them a bigger part of their offense this year.

The general concept is easy enough: the offense will isolate a defender who has both run and pass responsibilities. The quarterback reads what that guy decides to do, then either throws the pass if that guy attacks the run, or runs the running play if he stays back.

But they’re not good for all seasons—RPOs take advantage of players with both run and pass responsibilities. If there are none, or at least there are super-clear priorities, it’s hard to find a defender to put in a bind. For example Cover 1—which is still Michigan’s base play—has pretty clear-cut jobs for their man-on-man defenders, the linebackers are given small zones they can defend while hanging in to plug their gaps, and one safety is given free reign to roam the deep middle and clean up any runs that get through. But even Michigan can’t stay in Cover 1 forever (cough cough Durkin), and against option-y, spread-to-run teams you’re almost forced to get your safeties involved in the run game, and then once again you’re susceptible to the offense putting that guy in a run-pass bind.

So let’s see how they work.

Solving Stacked Boxes

While run options are an answer to the problem of how to involve your quarterback in the running game, run-pass options address a different age-old problem for offenses looking to run the ball successfully: defenders in the box.

[After the jump: locking them in the box]

For 60 years the holy grail of offensive coaching was to consistently win their six-on-six or seven-on-seven box battles, either by being so effective at passing that the defense has to underman the box, or so effective at running they have to underman the pass.

The box is loosely defined as the space between the inline offensive formation (OL plus TEs) and about seven yards from the line of scrimmage. But defenders will move around, and hang out on the edges, and, like, what if a safety is 9 yards away but running toward the line of scrimmage at the snap?

It’s probably more helpful to think of it as the area wherein a defender is near enough to read run and get to his gap quickly enough to make running through there a dead play. A defender out of the box is ceding yards that can be claimed by ballcarrier, and opening up space for the blockers to create lanes. But he’s also in better position to defend the pass and prevent long gains.

The offense’s formation in the gif above has 7 gaps. If there are seven guys in the box against this formation, it’s gonna be hard to run, since there’s somebody able to jam up whatever spot you’re attacking, plus the next one, plus the backside cut, etc. If there are six, it’s still hard to find the one spot with all the other lanes jammed up. So, not counting the quarterback, standard box math would have one less defender than there are offensive players. Against the 3-wide formation above, that means six is playing things even. In the old two-backs formations we grew up with that would mean 7 box defenders for 8 offensive attackers—which is how “8 in the box” became a byword for overplaying the run.

Stacking the box isn’t a guaranteed run stop; this got 10 yards for example, despite eight Colorado players in the box, because Michigan shifted the tight end and Colorado didn’t adjust, providing room for the running back to hit a B gap.

However run-pass box optimization remains one of the major cat and mouse games at all levels of football. If my 3-wide formation is consistently getting 5 or 6 yards per carry against six box defenders, you’ll have to under-defend the pass to stop that.

Particularly relevant for Michigan’s defense, run options have necessitated more guys in the box, even if they aren’t starting there by alignment. Remember Ohio State murderating the ‘15 defense with their inverted veer play?

When I went over that I said the way to solve it is to get the safety involved in run coverage instead of just hanging out there. Michigan used up a safety as a deep guy while Ohio State bought back its quarterback as a run attacker by optioning Wormley. Well, if you do that, you’ve got no more safety help. Ohio State has a

Pre-Snap Options

But what if you have a run play called and they’re stacking the box? Line checks and quick passing routes were the answer.

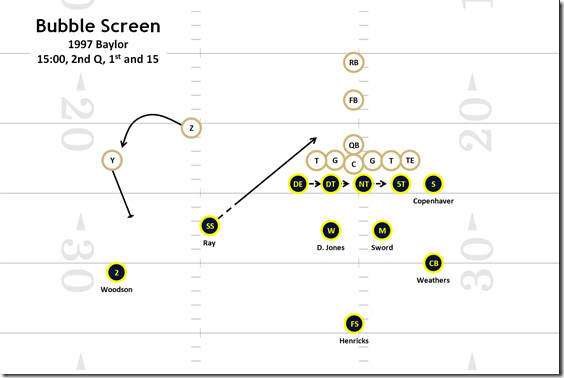

[clipped from Wolverine Historian]

In this totally random historical example I picked, Baylor would catch Michigan with a safety blitz. Marcus Ray isn’t technically in the “box” but once he comes down a bit he’s basically in the box, i.e. in position to stop a run outside that tackle for no gain. They have an answer for that: a quick check to the bubble screen.

This won them what should be a dominant matchup: a great offensive player with the ball, with a lead blocker vs a cornerback for all the yards. That cornerback would have to be the most outstanding player in college football in the United States to stop it for no gain.

Bubble screens are one example of easy throws, but common checks can also be slants, quick seams, post routes, or whatever, based on which defender is creeping into the box. But you have to have that in the playbook, have practiced it, and accurately catch the defense doing something.

Defenses obviously don’t want to just declare that they’re leaving a weakness so they will move guys around, have guys out of the box run into it at the snap, and hang out on the edges threatening either. Really you don’t really know until after the play’s begun.

Post-Snap Reading

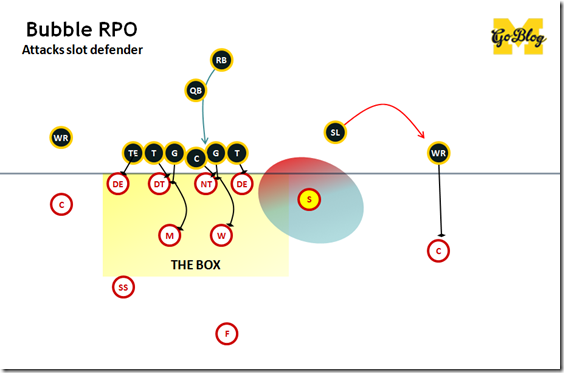

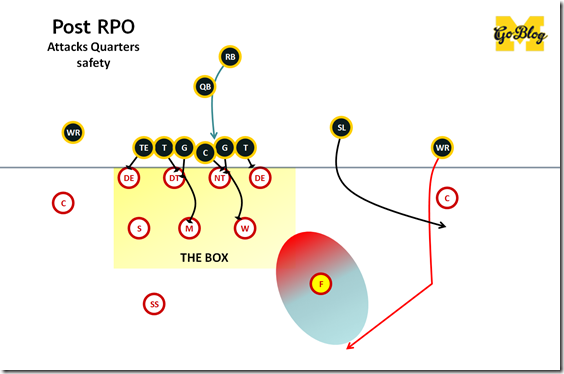

Run-pass options attempt to win the box wars by throwing or running after the snap. By spreading offensive weapons across the formation, the defense is forced to have defenders either wholly out of the box, or hanging out at its edges where they can still get out and cover their guys.

This is more like a “smash” or “high-low” concept in passing, except instead of reading between two receivers to either side of a zone, you’re stretching a run-pass defender’s zone (since that link is from 2010 I should probably make high-lows one of these segments).

As with high-low’ing, to catch a guy in a quandary you have to find him with multiple responsibilities. A given RPO play won’t work all day long—they’re best as constraints when the defense has shown you what they’re going to do against your thing.

Some examples are below; I’ve kept the same formation and used inside zone for the running play because it’s simple and common and the next opponent’s base running play, but you can do this with whatever your best run play is.

This one is a classic. Rich Rodriguez half-invented RPOs by having his zone read quarterbacks read this slot defender against his three-wides and throw the bubble to his slot bugs when the SAM came too far in—Pat White realized defenses would have that guy line up outside then come inside to tackle him, so White when White saw the DE crashing and the SAM coming down too, he’d throw the bubble late.

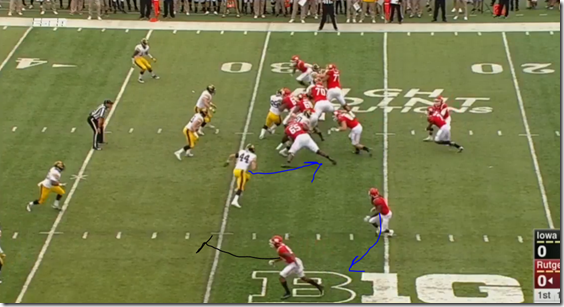

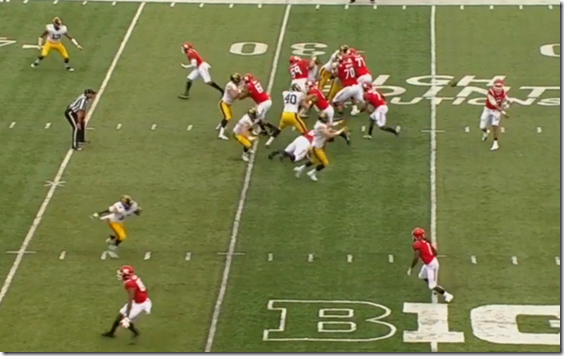

This is now a very common post-snap read, occasionally with a zone read element too. Here’s an example from Rutgers vs. Iowa this year. Rutgers will read the SAM linebacker at the snap and throw the bubble to Janarion Grant if that dude comes inside.

On the snap he does, but that might be a feint. Wait until he gets too far in to do anything about it and…

Bubble! The strong safety is now 10 yards away versus one of the most slippery dudes in the conference (or at least he was; Grant was injured in this game).

That went for 20 yards by the way.

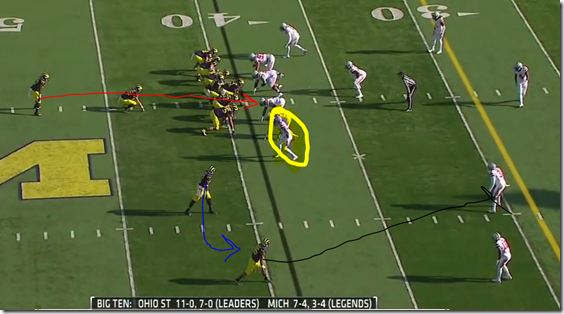

You may also remember Borges running this successfully in 2013:

By this point it’s on tape and Ohio State has adjusted like Iowa did by bringing the SAM to run blitz and checking Funchess with a safety. So for The Game Borges tweaked it a bit to have the safety blocked and put Funchess one on one with a cornerback/hurdle.

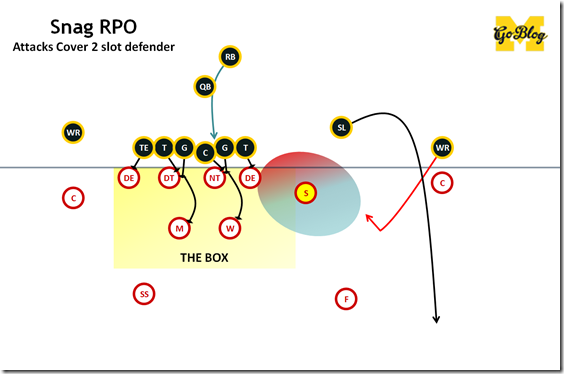

Since then however RPOs expanded to attack in all sorts of places. The snag package was Urban Meyer’s addition, attacking the same dude but with a guy appearing behind him:

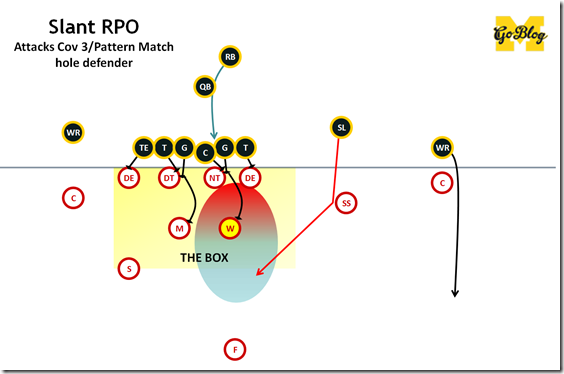

But a lot of defenses are Cover 3 or Saban-style pattern-matchers, with the wide slot covered by a safety-like hybrid space player who’s taking away the slot receiver and has the speed to get back for the run. Of course, that guy is expecting some help inside from a linebacker in the middle or “hole” zone. In other words there’s another guy who can be put in a bind:

These are all quick passes of course, and defenses these days are designed to take those away. In particular Quarters coverage managed to solve a lot of the spread and option offense stuff by having safeties reading inside receivers and coming down against the run if they’re not needed to stay on top. Except…

In 2014 Ohio State also attacked Michigan State with a 4-verts/outside zone RPO:

And then who can forget when Denard debuted the pop pass, where the quarterback starts to run outside with a lead blocker while reading the safety to that side, and if the guy freaks out because DENARD he threw it over the guy’s head.

Why Does This Happen to Everyone Else?

For one, Michigan doesn’t have to cheat to stop stuff. Like if Jabrill Peppers is your SAM, he’s so hard to block and so fast that screens to stretch his range merely end up proving it. What good is putting a defender in a run-pass option situation when he can routinely cover both?

That’s not true however of the other linebackers, nor the safeties. The other reason is we run a lot of man. Michigan last year and to a lesser degree this year is a very Cover 1 (man-free) defense. Man coverage has its own faults but it’s hard to RPO a man defense since nobody’s confused as to his priorities. Cover 1 is the ultimate “my guys versus your guys” defense, and Michigan’s been getting away with it because against most opponents, we have the guys.

However Michigan is playing more Cover 2 stuff these days, especially against spread teams. Even if they can shut down Rutgers while playing a man short in the box because of the talent disparity, the running game for the Scarlet Knights is good enough and the passing game is bad enough that Michigan should be doing some of what they’ll have to do against Ohio State, i.e. put some run-pass responsibilities on their cover guys. That means the safeties and linebackers will be exposed from time to time to RPO stuff.

Just Not Fair

The NFL’s rule is a blocker can’t go more than a yard downfield on a passing play; the NCAA’s rule is three yards. However in practice this is more like five yards, or doesn’t exist, no matter that NCAA officials keep saying they’re going to crack down. Sometimes you’ll even see a pass defender getting blocked by an offensive lineman downfield while the defender’s trying to defend the pass. You see a lot of this on RPOs, since the linemen are going to be acting like it’s a run regardless. Technically they’re supposed to not do that. Technically.

More Video

I had trouble making clips today but this video does a pretty good job of explaining the rock, paper, scissors involved in calling RPOs: