“The more you tighten your grip, Governor Tarkin, the more star systems will slip through your fingers.” –Princess Leia

It is one of the easiest ways to sound like a knowledgeable football watcher: The pass rush is closing in. The receivers are all covered. Then suddenly the quarterback is running through air. “Contain!” you yell with appropriate obviousness to the people who obviously aren’t paying attention. “You must keep contain!”

CONTAIN

Contain is a concept put in every play design, a plan to be understood before every snap, and a mantra to keep in mind. “Contain” isn’t limited to pass rush; in fact it’s exactly what a Force Player is doing on any given run. Coaches don’t use this term so often—rather you’ll hear them talk about “lane integrity” or “leverage”.

GAP/LANE INTEGRITY

Before the snap, every play is a running play, because that’s where the ball is. No matter the defense, the defenders will have gap responsibilities, sometimes more than one.

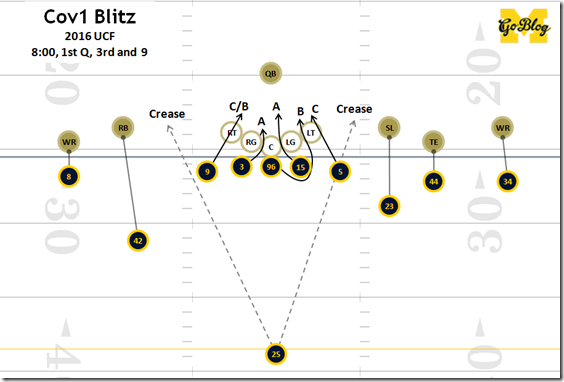

GAPS: Are usually labeled A to whatever. Brown doesn’t go beyond D (which he defines as off a tight end’s butt). The A gaps are between the center and the guards. B gaps are between the guards and tackles. C gaps are between the tackles and whatever tight ends or backfield material exists.

[Hit THE JUMP to solve the mystery]

Pulling and lead blocking will add gaps or move them around, so defenders have various “Keys” (dependent on the offense’s tendencies) for how to react to that. For example against an offense that uses lots of fullback lead blocking, a linebacker responsible for that fullback in coverage will react to the fullback’s first step forward by shooting up into his gap and popping the fullback. Or a backside linebacker will react to a guard pulling by attacking the frontside shoulder of that guard. Or maybe a tight end coming in motion will alert an outside linebacker that he’s to attack the next inside gap.

PERIMETER SUPPORT: I wrote a thing on the outside lanes before. The crease, alley, and outside lines are usually covered by space players and defensive backs. Interior lanes are usually reserved for linemen and linebackers, since the close space means you’re more likely to have to bang into someone to keep your lane integrity. Here’s the run assignments against trey in Michigan’s normal alignment:

OL are shaded to show alignment of the DL—the nose is on the left guard’s inside shoulder for example—but that’s also an indicator of their lane responsibilities.

There’s one extra gap because the running back (green dot) might run to either side. The free safety has the middle 1/3rd of the field in coverage, but he’s also lined up over the running back for a reason: if he heads outside to create an extra crease, that’s the FS’s responsibility. He’s technically two-gapping; free from blockers back there, provided everybody else is doing their jobs, by the time the ball gets to where the free safety is needed he’s had plenty of time to react and close down that space.

TWO-GAPPING: This is just 3-wide and you can count 11 possible lanes. So no, all 11 defenders aren’t always given one lane: often they’re tasked with two-gapping. Two-gapping linemen do this by dominating their blocker so they can threaten to either side (a true 3-4 like UCF’s will do this almost every play. But you can also have a safety watching multiple perimeter gaps. A cornerback who’s carrying a receiver deep still technically has the lane outside that receiver—since that won’t matter unless the running play gets that far downfield it’s a moot point, but those assignments become key to defending WR screens.

Michigan will two-gap with linemen often when pass-rushing. You’ll see Taco do it for example by blasting the OT back until the pocket collapses. That sort of dominance allows Taco to attack the quarterback to either side of that blocker. Taco is great at this. It’s also dangerous.

The point is control, not placement. Whatever happens next, you have to CONTROL your gap.

LEVERAGE: Coaches will also talk about “Leverage.” Your gap is one thing, but being in position to keep your gap where it belongs is also crucial. That is leverage: being in position to control your gap and attack the ball if it comes there. If you’re in your gap and facing away from the ballcarrier, you don’t have leverage. If you get way upfield, or get blown downfield, or get kicked way outside so your buddy’s now defending a lane big enough to drive a house through, you’ve lost leverage.

On the other hand if your lane is the “A” gap and you’ve blown the center into the guard on your way into the backfield, and you’re still on your feet and in control, well, you’ve still got leverage to keep the ball from attacking your gap and to force the ballcarrier into your friends. You gain leverage by taking it away from your opponent: dominate the correct shoulder, fight your way back if you’re getting pushed out of your lane, and always be in position to affect as much space as possible.

PASS RUSHING CONTAIN: In a passing context, it means to cut off the quarterback’s escape routes so he can’t run away from the rest of your pass rush. You do this by controlling your lane and gaining leverage. A pass rusher has a hierarchy of responsibilities. Grossly simplified they are:

- ID and get into your blocker. Get your hands on him, don’t let him do whatever he’s trying to do to you. You want to close the distance as soon as possible and fight off his hands so he can’t keep you at length.

- Control your lane. You don’t widen on your initial steps, and you don’t let the OL get you out of your lane. If you feel that happening, you fight back to where you belong. Even if you’re not in your gap, compressing the space between the lineman blocking you and the next guy will control your lane.

- Beat the blocking. Rip, punch, whatever: there are lots of techniques for getting by your blocker, and he’s got lots of techniques to match you. It’s a mini-game. But for him keeping you from the quarterback is Job 1; for you getting past him is job 3 after controlling him and controlling your lane.

- Attack the passer. Once you’ve made contact with your blocker you get your eyes on the ball so you’ll know whether to put your hands up to block, whether to slow up to cut off his escape from your buddy, or whether to pounce now. You don’t jump, and you don’t hit the gas, because if the quarterback goes under you it’s all for naught. Arrive in control.

THAT SOUNDS EASY. LET’S YELL IT!

This isn’t as simple as it sounds. Competitive athletes want to destroy the blocking and end the play as soon as possible, so yes, sometimes they just get out of control. You don’t want to nerf your defense’s aggressive instincts though. This game was a good example, as in the first half Michigan gave up lots of long QB scrambles by losing contain, and in the second half they played their ends more conservatively, meaning instead of sacks the quarterback had the opportunity to roll out of the pocket and throw it away down the sideline. It’s a dial, adjusted by what you can get away with and other strategic goals, not a hard and fast rule.

As a result the techniques that defenders learn to keep contain are often more about precision than holding back.

TRENCH WARFARE

But pass rushing is a bit different. The call I’m familiar with is “HIGH HAT” or “LOW HAT”. The hat in this case is the quarterback’s. If he’s standing up his hat is high—you are defending a pass. If his hat is low he is handing off or faking a handoff—you are playing a run. Those terms persist, but at every level higher than what they’d ever let me play defensive linemen aren’t keying the QB usually.

They’re playing against their blockers. High level lineman play kind of becomes a super-mean version of the hand slap game (warning: link contains Seagal). The DL have moves, the OL have counter-moves, and over the course of one game these matchups can get dang intense.

The war is also uneven. Strongside contain is more conservative than backside contain, since quarterbacks will more often see and be in a position to attack a hole right in front of them, and offenses often do things to run off the help defenders on that side. Regardless of formation strength or where the tight ends are, pass rushers can be more aggressive behind a quarterback’s back because the time it takes the QB to turn around and run provides a window to pursue.

This aggressiveness is important for generating pass rush, but it’s also a recipe for the rushers to go off script.

GOOD CONTAIN:

Below is Hill’s pick six from the Hawaii game. I want you to watch McCray, the linebacker who’s lined up inside Hawaii’s right tackle:

McCray controlled his blocker by winning the arm battle, then got WIDE, saw the RB set up to help on him, and only then attacked that D gap.

McCray’s technically pass rushing—I mean the guy’s blitzing—but he’s got a tackle who could push him wide and an eligible receiver (the RB) so he’s being cautious in his approach, putting himself where he can make sure the QB doesn’t escape.

Everybody has a lane somewhere. McCray’s is between the OT and the RB. Outside of him, in the “alley”, Delano Hill is in position to come up on a scramble. Mone, Winovich and Wormley are breaking through but they’re also closing in without getting out of their lanes. Godin stunted outside and is in the same position as McCray. Wormley can use the success of his friends to get aggressively upfield against a guard, and that threatens a sack if the QB doesn’t throw it RIGHT NOW…to Delano Hill.

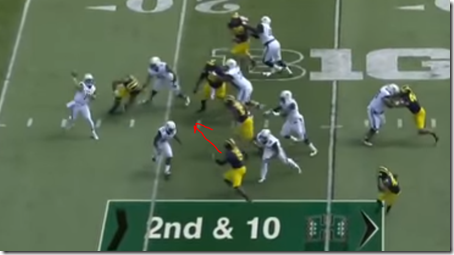

BAD CONTAIN:

I’m guessing that when Gedeon got matched one on one with the slot receiver that McCray was supposed to take both the C and B gaps, with Thomas covering the crease. Like so:

I’m basing that on Gary plunging into the A gap off the snap (if he blasted the guard then Gary might have been two-gapping but going for the space between the guard and center like he did says to me that this was his assignment. It also makes sense since that occupies the center who might need to be helping the left guard deal with Winovich, since Glasgow is stunting over to the backside B gap.

Glasgow and Winovich put on a stunt that almost got Winovich in for a sack. And he would have gotten away with it too, but McCray’s outside rush got mirrored by the OT and thus McCray wound up too far upfield to control the C gap. Not in lane, no leverage = bad contain.