You have read somewhere that power offenses like Michigan are often dependent on winning big, strong, man-a-mano battles. While that's quite an oversimplification, it's also a truth. Run defenders are usually given pretty simple assignments like "defend this gap at all costs!" or "don't let anyone outside you and hit anyone who tries" so confusing them into leaving your lane open is not sustainable. Sometimes you just need to shove the dude out of the way to make a gap. Sometimes you gotta…

[MC5 lyric you know is coming is not safe for work]

There's plenty going on in that play, but we're going to focus on two opposing concepts that are in play on just about every running play:

FORCE PLAYER

Fritz Shurmer:

"The defender who is responsible for tackling or making sure the ballcarrier does not get outside of him. It is his responsibility either to tackle the ballcarrier or to force him to cut back into the pursuit pattern."

I took that quote from a coachoover post post worth reading. The force defender is being pulled in two directions. He MUST set up far enough outside that he won't get edged, but he's also got to be far enough inside to keep the gap small. Typically you put a little money in the bank; if the ballcarrier tries to go outside of you he's going to either run right into you or the sideline. The sideline is helpful but also passive. Better to redirect the ballcarrier to your friends.

That said, the force defender can't be too conservative. Goal A is set the edge, but every step towards the edge is a lane that's one step wider. The force defender sets up at a 45 degree angle, able to attack upfield or across it. That setup also gives him leverage to not get blown back by a…

KICKOUT BLOCK

Football Outsiders:

Kickout block– On a running play, this blocker is running parallel to the line of scrimmage and his job is to to keep the outside edge rusher (usually a DE or OLB*) from crashing to the inside. It's almost always a fullback or a pulling guard who does the kickout block. Opposite of a crackback block.

* [or, like in the video above, a Cover 2 cornerback.]

If a force player has done his job well, there isn't much space between the force player's area of effect and the defensive pursuit. A kickout block attacks the force defender, thwacking him toward the sideline, preventing him from a tackle attempt, and creating a running lane over the resulting viscera. That's why FO says it's almost always an offensive lineman or fullback.

A kickout block is going to go as well as physics allow: the more accelerated mass you can hit him with, the more room there is to run.

[Hit THE JUMP to see it in action]

HOW DO YOU DO THAT?

A kickout block isn't as footwork dependent as other blocks—the contact and leverage at the contact point are the big things. A kickout blocker wants to be the low man, bent at the waist with his body weight over his butt, when the impact occurs, so he can then spring up and into the defender, popping that guy out of the hole. Then the blocker maintains contact and tries to continue shoving that dude toward the sideline, or if the defender won't budge, deep into the bowels of the Earth.

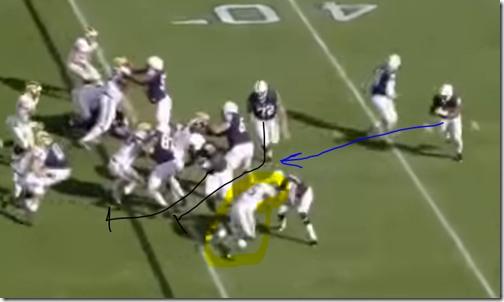

A close cousin of the kickout is the "Log" block, where you run the defender upfield to widen the gap and cut off pursuit. The way this goes is rarely in the playcall—you get the best block you can, with the goal always to keep that guy sealed outside and expand the running lane. Like, Magnuson in our image just put a leaping 300-pound man in between the force defender's knees and the ballcarrier, turning his kickout into a cut block. This is about function not form.

IS THAT IT?

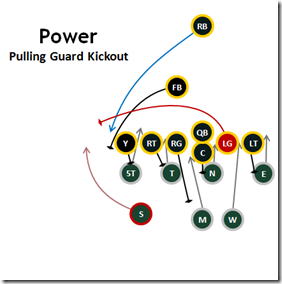

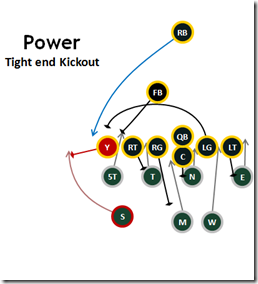

Let's look at a typical "Power" play. That's the base Manball running play where the backside guard pulls, everyone else blocks down, and the back hits the resulting hole behind a lead blocker.

Your standard 4-3 defense is going to fill those lineman gaps with their DL and middle linebackers, since those guys are built for contact. Here a standard 4-3 is planning to have their SAM be the force player—that keeps the defensive backs focused on covering things.

If the force player knows who's coming to hit him, though, he can get aggressive: make that collision occur in the backfield or relatively tight to the rest of the defense, giving the ballcarrier nowhere to run. If your running play will live or die on the kickout block you really don't want the guy getting kicked to be doing that. So you change up who whacks him.

On Power the guard and fullback are usually blocking whoever shows, so on the same playcall you might have one block the force player or the other. The play on the right is a "wham" block with the fullback. As you can guess, tight ends become kick blockers all the time in one-back offenses.

Back when fullbacks were on the field 90% of the time, defenses liked big-ass SAMs with neck rolls: a Clint Copenhaver or Victor Hobson, and that was because these collisions happened so often that how much your SAM moves when he's hit by a fullback might decide how your day goes.

These days a SAM is more often than not a hybrid safety, e.g. Jabrill Peppers, a guy who uses his speed and agility to dodge blockers far more often than he's using his size to rock them back. If circumstances make him the force player, he's got to get more creative than setting up outside and waiting for contact. You may remember James Ross in this role, ably firing into the edge

Ross is set up near the line of scrimmage at the bottom of your screen. The H-back would like to kick him out of that hole since two guards are pulling on a sweep:

Ross set that edge by screaming into the H-back. He's on the correct shoulder to not allow Barkley outside (that would be very bad) before safety help can come down, but the impactful moment also gave Ross leverage he wouldn't have had if he was a stationary target. Whether Ross makes the tackle or another guy does, such a clear victory in the Force vs. Kickout battle has killed an otherwise dangerous running play for a four-yard loss.

IT'S NEVER THAT SIMPLE, ESPECIALLY WITH HARBAUGH

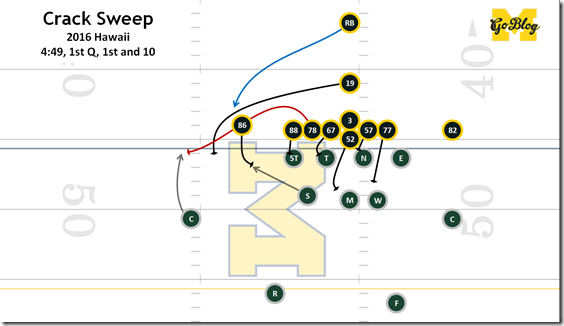

But a kickout block doesn't just happen one way. In fact Harbaugh's running game is notorious for kickout blocks appearing all over the dang place. In the example above it's a pulling tackle, Erik Magnuson, kicking out a cornerback, who became the force defender when Chesson motioned in and cracked the SAM.

Hawaii's basic playcall helped this because the Rainbow Warrior DL were getting upfield and attacking inside gaps, meaning Butt, Kalis and Kugler all got to essentially Reach Block the guys opposite them. Chesson's crack block on the SAM won Michigan a big gain by taking out a bigger guy with a receiver so Michigan's own big guy, Magnuson, could match up with a guy designed to cover Chessons.

This year you will also see Michigan's interior linemen step down and kick out a tackle for runs meant to go inside, or running backs kicking out defensive ends on a fullback dive, and all sorts of other weird ways of setting up mismatches like Magnuson vs a Hawaii cornerback, while keeping defenders constantly wondering where the next kick will come from.

SO WHAT AM I LOOKING FOR?

When you see a running play developing, shift your eyes to the edge they're attacking, even if the play cuts inside. Zone or power, spread or manball, there will always be a force player setting up to either side of the play, or setting up to scream out there at the right moment. Watch what happens to that guy.