[Bryan Fuller]

You're going to have to bear with me on the offensive UFRs this year. The last time I saw a traditional gap-blocked, regular-ol-QB offense for anything more than a one-game debacle was ten years ago. That was the first year I did UFR and most running plays of that sort were deemed "another wad of bodies" because I didn't know what I was looking at. Since then:

- Two years of Debord running almost nothing but outside zone

- Three years of Rodriguez running inside and outside zone with a little power frippery

- Two years of Hoke trying to shoehorn Denard Robinson into a pro-style offense, giving up, and running a low-rent spread offense

- Al Borges's Cheesecake Factory offense that ran everything terribly

- Doug Nussmeier's inside zone-based offense.

I've seen plenty of power plays. Most of them were constraints that could be run simply and still succeed because the offense's backbone was something else. The rest were so miserably executed that they offered no knowledge about what power is actually supposed to look like. I watched a bunch of Stanford but not in the kind of detail I get down to with the UFRs.

![fbz3gg1_thumb[1]](http://mgoblog.com/sites/mgoblog.com/files/images/655ca1995608_CE7E/fbz3gg1_thumb1.png) One thing that I am pretty sure I think is that the popular conception of power as a decision-free zone in which moving guys off the ball gets you yards is incomplete. Defenses will show you a front pre-snap. You will make blocking decisions based on that front. Then the defense will blitz and slant to foul your decisions and remove the gap you want to hit. If you do not adjust to what is happening in front of you then you run into bodies and everyone is sad.

One thing that I am pretty sure I think is that the popular conception of power as a decision-free zone in which moving guys off the ball gets you yards is incomplete. Defenses will show you a front pre-snap. You will make blocking decisions based on that front. Then the defense will blitz and slant to foul your decisions and remove the gap you want to hit. If you do not adjust to what is happening in front of you then you run into bodies and everyone is sad.

What Stanford was great at was running power that was executed so consistently well that it was largely impervious to all the games defenses played. This requires linemen who are downblocking to think on their feet, maintain their balance, and stay attached to guys who may be going in directions they were not expected to. It requires everyone off the line of scrimmage (tailback, fullback, pulling G) to see what's in front of them and adjust accordingly.

Michigan did a bad job of this against Utah. They also got blown backwards too much, complicating decisions for the backfield. The latter was not a problem against a much weaker Oregon State outfit. The former was much better, and that's the most encouraging thing to take from this game.

Here's an example. It's a six yard run in the first quarter on which Oregon State sends a blitz that Michigan recognizes and thwarts. There's no puller on this play; I think it was intended to be a weakside iso that ends up looking not very much like iso because Michigan adjusts post-snap.

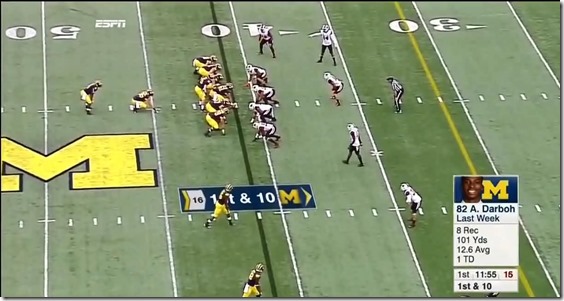

M comes out in an I-Form twins formation; Oregon state is in a 4-3 that shifts away from the run strength of Michigan's formation. They are also walking a DB to the line of scrimmage:

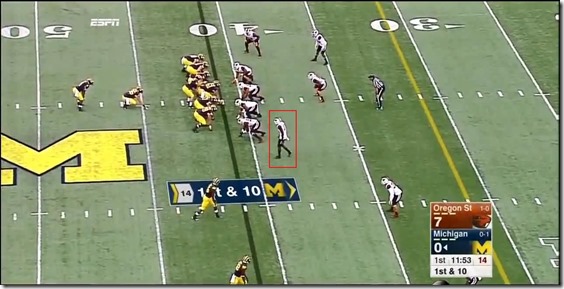

By the time Michigan snaps the ball this DB is hanging out in a zone with no eligible receiver while both WRs get guys who look to be in man coverage. This is not disguised well unless the highlighted player is Jabrill Peppers and can teleport places after the snap:

He's going to blitz and the DL is going to slant to the run strength of the line. Michigan will pick this up, and I wonder if they IDed the likelihood of this pre-snap. No way to tell, obviously.

On the snap both the FB and RB start to the weak side of the formation; you can see Erik Magnuson start to set up as if he is going to execute a kickout block on the defensive end:

With the blitz and slant from the Oregon DL that's not going to happen. Each Oregon State DL has popped into a gap. Kerridge is taking a flight path to the gap that would normally open between Magnuson and Kalis, the right guard, on a play without this blitz. Without the blitz the DE would be the force player tasked with keeping the play inside of him; Magnuson would have a relatively easy job as he and the DE mutually agreed on where he should go.

Here the DE threatens the play's intended gap. Magnuson can't do anything about that. The D mostly gets to choose what gap they go in, and it's up to the offense to roll with the punches.

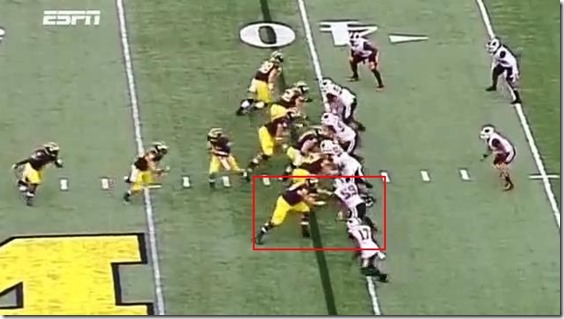

Michigan does this:

A moment later Magnuson has changed his tack from attempted kickout to an attempt to laterally displace the DE using his own momentum. Kerridge has abandoned the idea of hitting the weakside B gap and is flaring out for the blitzer.

Thunk:

Now, this could be successful for Oregon State still. The slant got five Michigan OL to block four guys. Nobody got downfield; the slant got a 2 for 1. But their MLB has stood stock still for much of this play, and Magnuson ends up shoving his dude past the hash mark—+1, sir. This is a ton of space to shut down, and De'Veon Smith is the kind of back that can plow through you for YAC.

Smith fends off the linebacker with a stiffarm and starts gaining yardage outside; it could be a good deal more but Chesson misses a cut* and the DB forces it back, creating a big ol' pile:

Second and four sounds a lot better than second and eleven.

*[Drake Harris will later pick up a 15-yard penalty for a similar, but more successful cut block; the genesis of that flag is probably Gary Andersen doing some screaming at the official after this play.]

Video

Slow:

Items of interest

You don't get to pick the gap even if it's gap blocking. Defenses slant constantly, and often in a specific effort to foul the intended hole and pop the back out into a place where an unblocked guy can hit. Post-snap adaptation is a must for a well-oiled power running game.

Slants win if they suck away an extra blocker. I would be peeved at the MLB if I was Oregon State UFR guy. While Michigan adapts to the slant well enough to provide a crease for Smith, the blitz means Michigan had to spend a blocker on the defensive back and the MLB is a free hitter. He should be moving to this more quickly than he does.

Slants also tend to open up giant running gaps. Adjustments like the above will often lead to a defender running in one direction suddenly getting unwanted help from an OL. If the OL can redirect and latch on just about everyone is going for a ride here. Once Magnuson locks on and Kerridge targets the DB these are two blocks that are easy to win and Smith is going to have a truck lane.

Given how much space Smith has even a linebacker playing this aggressively who shows up in the gap might lose or get his tackle run through; Michigan's getting yards here, whether it's three or six or more if Chesson gets a good block.

In the past this site has seen arguments about whether meeting an unblocked safety at or near the line of scrimmage is a win for the offense or the defense. I have largely come down on the side of "that absolutely sucks," but when the hole is so big that the defender is attempting to make an open-field tackle it's a lot more appealing.

Michigan WRs need to be more careful with the cut blocks. You can cut a guy from the "front," by which the NCAA means the area from 10 to 2 on a clock. (Seriously, that's the way it's defined in the rulebook.) This was very close to a flag, and Michigan got one later.

I wish Michigan was running pop passes, as those are good ways to get defensive backs hesitant about running hard after plays like this. Maybe in a bit.