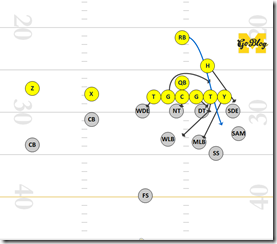

What is the difference between this run:

…and this run:

?

If you guessed "the one Harbaugh/Drevno were coaching got yards and the one from Hoke/Borges didn't" you win a running theme of the 2015 offseason. The results are certainly stark; why that's true is what we're interested in.

The Power Play

These are both the same play by the offense, and the same play Brady Hoke promised to make into Michigan's base because it is the manliest of plays. It is Power-O, the one where you pull the backside guard and try to run between the tackles.

You can click for biggers

The play is relatively simple to draw up and complex to execute because it uses a lot of the things zone blocking does, including having the blocking and back react to what the defense does. For all the "manball" talk this isn't ISO, where you slam into each other quickly. Depending on how the coach wants to play it and what defensive alignment you see, the basic gist is to get a double or scoop of the playside DT and kick out the playside DE, then have an avalanche of bodies pour into that hole—if the defense is leaping into that gap you adjust by trying a different hole further outside. Leaving two blockers to seal off the backside, one blocker, usually the backside guard, pulls and becomes the lead blocker—it's up to him to adjust to what he sees when he arrives.

You can run this out of different formations with different personnel, and the one immediately apparent difference in the above diagrams is Michigan was more spread—a flanker (Z) is out on the opposite numbers and the strongside is to the boundary; after the motion this is an "Ace Twins". Stanford ran this with a heavy "22-I" formation, meaning two backs (RB and FB) and two tight ends (Y and H) in an I-form. The benefit Michigan gets from its formation is the guy Stanford would have to block with its fullback Michigan has removed from the play entirely by forcing him to cover the opposite sideline.

What Stanford gets in return for its fullback is matchup problems: the open side of the field is going to be two tight ends and a fullback versus two safeties and a cornerback. Run or pass that can go badly for the defense as these size mismatches turn into lithe safeties eating low-centered fullbacks, and dainty corners on manbeast TEs.

In War of 1812 terms, Michigan is the Americans, sending the fast-sailing frigate Essex in the Pacific so the enemy has to move ships to the Galapagos instead of harassing the Carolinas. Stanford is the British, parking 74-guns ships of the line where engaging them cannot be avoided and trusting the outcome of any forced engagement should turn in their favor. The point is both work to the advantages and disadvantages of the talent on hand. (In this analogy Borges is a guy trying to use Horatio Nelson tactics with a Navy of sloops and brigs).

That being said, it still works as well as anything—people did in fact score points before the spread, and those who scored a lot of them could do so by keeping defenses off balance and with good execution. As we'll see both of those factors played a big role.

[after the jump]

The Defenses

Both were run into aggressive, run-squelching 8-man fronts. Michigan had an extra wideout instead of a fullback, whereas Stanford was facing nearly 9 in the box when you count the cornerback just outside it.

Note however the substantial lack of respect UConn's defenders gave to the possibility of the Y-tight end, A.J. Williams, as a passing threat. The free safety and the CBs are playing 3-on-2 against Michigan's real passing threats, and the SS went in motion with Butt, the U- or H-back, but their answer for Williams is for the SDE to get a chuck and the SAM to cover. This was a constant X's and O's complaint during the Hoke era: this would be a play on which Williams actually got a good block, but either his blocks have to be superb (i.e. take out two guys) or the offense has to create a different passing threat to his side to prevent defenses from activating pass defenders against the run.

On the Stanford side the CB could not be left to fend for himself against the split end (X) to put safety help over the side with two tight ends, so that strong safety has to range the middle and indeed arrives too late and at a bad angle to stop the run for minimal gain as he should. As UConn did, the safety over the H-back went in motion when he did, and became the force (edge) defender to that new side.

Also note that Virginia Tech was slanting the DTs. This curveball put the Hokies at a matchup disadvantage since it's linebackers rather than tackles the offense has to shove out of the way to playside, but it also gave the offense something to adjust to, another thing that can break in a game of "don't screw up." As you see the run fits were still sound.

In the UConn UFR Brian gave the Michigan play an RPS-2 because Borges ran into a stacked box. You can mentally give Stanford an RPS+1 because they ran against a slant. The coordinators calling plays however is really not the main thing going on here—VT's defense is sound and UConn's is beatable. What they'd shown each other before matters much—VT is still playing this with is base nickel(!) personnel because Andrew Luck plus those tight ends is a substantial passing threat.

The Execution

The biggest reason Michigan's attack got zero yards and Stanford's got all the yards, in my opinion—and shared by a couple of former linemen I ran this by—was the execution of the offensive players themselves, and particularly the interior linemen and running backs.

Here's what happened after the snap on each:

If you have Gifscrubber I suggest you pull it out because it's enlightening to watch this frame-by-frame. We'll start with Frame 6:

Note two spots here. The first is on the top of the formation, Michigan's H-back, Jake Butt, is heading for the same force defender that Stanford's is:

…but he started a little further in the backfield after his motion, and is thus four yards off the line of scrimmage. The faster he gets to this block, the less upfield the force defender can get, and the more space there will be for the offense to operate.

The other important thing here is that right guard. You have a zoom in a bit to see it well, but Kalis is a yard further back in the backfield, and can't get any further across the formation until the quarterback drops past him. Stanford's guard actually lined up a little further off the line. I talked to one former OG who told me that is a typical trick of offenses that run a lot of power. You give up some space if you're running to that side, so you can tip off to a smart defense what play you're running (power or pass pro). The upside is you get a much cleaner release.

Here it makes a huge difference. While Kalis has to loop four yards into the backfield on his pull, first to get under the quarterback and also to dodge Miller's seal on the nose, Stanford's right guard has a good yard of space between the QB and the center he can scoot through. He's also enough of an athlete to be able to shuffle instead of "rip and run" as profoundly less athletic dudes like myself would have to.

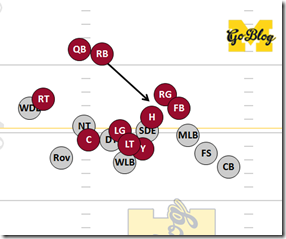

We get the results from these delays a few frames later when the handoff has been made:

The Stanford right guard is that guy a line off the LOS, covering up the H-back who's about to block the backer. I'll draw these so it's a bit more clear where everyone is:

In both cases the rest of the blocking has gone well enough, Stanford's thanks to the slant and Michigan's thanks to A.J. Williams's great block on the MLB that made life hard on anyone trying to pursue from the backside. So now in both cases it's down to 2-on-2: RB and RG vs. two unblocked defenders, to decide the outcome of the play.

(If this was some kind of option, e.g. zone read, instead of under-center Manball, the offense would have a 3-on-2. So it goes.)

This is where those blocks above matter. The Stanford H-back got pushed further upfield but he also sealed the SDE inside; the running back sees this and hits the accelerator to the next gap. Michigan's got one less guy to contend with but the SDE block didn't happen as fast so that defender is making the RB and RG gap decisions more difficult. The bigger problem is the RG, Kalis, wasn't to his station on time. Whereas Stanford's guard got his release, stayed close to the line of scrimmage, and shuffled into position while sipping tea and choosing a victim, Kalis is going to arrive a nanosecond before he has to decide whom to block. In fact Toussaint takes a little bounce to give his blocking more time to set up and maybe get those defenders to bite outside.

And here's where the plays go in two completely different directions. Kalis blocks the SAM, the edge defender, so Toussaint has to beat that strong safety standing alone on the 30 yard line, either by catching him inside and going outside of Kalis's block, or by getting him to jump outside then hitting up inside.

And Stanford? With time to survey and plenty of practice working together and seeing these things happen, the right guard and fullback perfectly coordinate dual-impacts with the two inside players, and the RB shoots through behind them. The safety guarding the edge cannot turn in time, the linebacker getting held a little can't recover, and the rover who's got a chance to stop this for 5 to 8 yards by flowing down the line is a little bit off-balance and can't do so. Touchdown.

Lessons:

1. This stuff all works. Remember what I said about 74-gun ships of line though: Michigan doesn't have a powerful fleet of tight ends and fullbacks yet to create the kind of respect Stanford got, let alone Andrew Luck. I am a spread zealot but I am foremost a Michigan fan, and if Michigan gets yards and points by performing Pirates of Penzance, call me a Gilbert & Sullivan fan.

2. Manball is hard to do right. Pulling is a difficult procedure that requires a lot of practice and a really smart and agile dude to pull off. And if you're going to do anything besides pulling it requires that guy to be huge and devastating. If you think a redshirt freshman (Kalis) ought to have been good at this, go put yourself in his shoes, or Toussaint's shoes, or any of these guys.

The reason Stanford got 60 yards and Michigan got zero when their respective plays got them effectively the same result up to that point was Jeremy Stewart ran toward the hole his blockers were able to punch open at the key moment, while Fitzgerald Toussaint was bouncing around waiting for various single executions to occur in hopes they made a gaping hole. Coaches will look at this kind of stuff and say "Team" with moist eyes, and to this degree they're correct. You can look at any individual Michigan player and explain how he was doing his job and just trying to be right on the various selections he had to make, but when you see Stanford's offense attack on this play they're operating like one machine. It is rare to be that good, but it only needs to happen once a game to be the difference between 4.6 YPC and 2.0 YPC.

Stanford did that to Virginia Tech's great defense; Michigan fopped it against UConn, because coaching makes a huge difference and things that are hard to do take years of practice to get right consistently.

3. Personnel matters a great deal. Stanford's center got downfield and actually got just enough of the Rover to make him stumble when the RB went screaming past. Michigan's center did as good a job as you could ask from Jack Miller, getting the NT sealed without needing any help. But Miller is a bit undersized for Manball and even on this play you saw he got knocked back into Kalis's path a bit. If you can't cave the defensive line you can't get a blocker across the formation. A SKRONG center is probably going to have a clearer path to playing time in this offense than a crafty one.