Next time you see this you'll know what's going on

In previous layman's discussions on how fancy newfangled anti-spread defenses function I've talked about how Quarters works, and how MSU used aggressive alignments with it to dominate the run game at the cost of greater risk of getting beat over the top. Each time I alluded to the fact that Saban's defense is similar in concept except where Quarters is a Cover 2/Cover 4 hybrid, Saban's is a Cover 3/Cover 1 hybrid.

We will see it this year. Every defense uses some Cover 3 and Cover 1 as a changeup, but Saban's base system, now all over the SEC, has spread into various Michigan opponents. Penn State kept it around while transitioning to Bob Shoop's version of Quarters. Maryland had it last year; not sure if their 4-3 transition includes a coverage shift. I think BYU (which is going back to 3-3-5 with Bronco Mendenhall overseeing it personally) is expected to as well. Michigan State has played with it, since it's similar to what they do normally. Anyway I thought it'd be fun to get into it now, so we'll have it to reference later.

Resources/hat tips:

- Rufio of Cleveland Browns SBNation blog Dawgs by Nature.

- Matthew Brophy's incomparable series on Alabama's D: part i, part ii, part iii, and his "Rip/Liz" video.

- Eleven Warriors' Kyle Jones's film study

- Ricky Muncie of Crimson Tide SBNation blog Roll Bama Roll

- Chris Brown, of course. Of course.

- Pre-emptive thanks to actual football coaches who post in the comments and point out where I got something wrong or over-simplified.

I'm Not a Coach Disclaimer

I'm not a football coach. I'm a guy on the internet who read a lot about football.

Basics of One-High Defenses

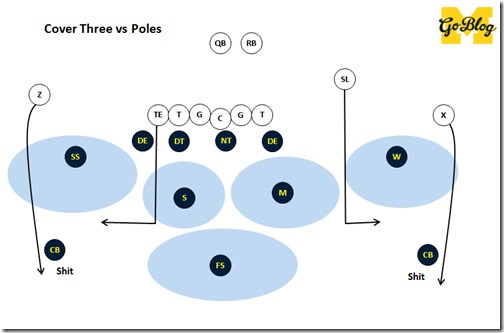

Cover 3 is probably the most basic defense in existence. It is the defense you learn on Day 1 as a high school freshman, if not before. At that level it is a "go to this spot and then find work" scheme, past that there are techniques coaches teach to cover the gaps. Here are the two basic versions that Saban uses against standard 2x2 formations:

If you picked up on the fact that "Liz" and "Rip" begin with the same letters as "left" and "right" (or you know your port and starboard colors) you have my permission to eat a cookie.

Joe Paterno used variations of this (Rip is very close to his base defense*) since the Chatelperronian, and like Neanderthal toolkits it only looks crude until you see it in the hands of a master.**

Some things to know that we'll use later:

- The receiver numbering system is the same as in Quarters: start from the sideline and work your way in until you're at the center. It's where they are at the snap, not before, in case motion messed with that.

- The path you take to your zone matters a great deal. Note how guys running toward their zones are actually going through weak points in the coverage. This is for "routing" purposes: if you're there a receiver can't be.

The latter is true for all zone defenses, but it's a stress point for Cover 3 because the holes in the zone are places the offense can attack either quickly (7-9 yards downfield in the seam) or easily (deep downfield once the free safety has committed). Cover 3 coaches teach defenders to be in the way so receivers have to re-route to covered places.

The tradeoff is natural coverage strength to the middle of the field, to the detriment of the flats—if you've ever watched an NFL defense that seems to constantly be tackling fullbacks squirting out of the backfield, that's why.

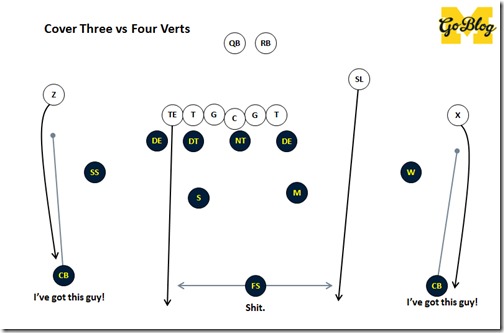

The problem with Cover 3 is the same problem with Cover 2: those frikkity vertical routes:

The problem remains with pretty much any set of routes that stem from a vertical release.

The old-fashioned answer to this is play more man defense, and certainly Cover 1 (example diagram) is a complementary coverage to any Cover 3 team. In Cov1, aka "Man Free" defense, corners stay on the receivers, the erstwhile "curl/flat" guys stay on the #2's, and the middle linebacker over the RB takes the RB.

But if you're playing man-to-man defense, you'd better have men who can win their battles 97%+ of the time against theirs. If you need to activate that free safety to double up a dangerman, now you're giving up "front"—how many defenders are participating in your run fits, and once it's not an 8-man front anymore you're weak against the run. Offenses will also use rub routes, or exploit matchups, e.g. have a quick slot receiver sprint across the formation until he loses the linebacker trying to keep up.

These were problems for Saban to a much greater degree when he was dealing with the kind of talent the Cleveland Browns drafted during his DC days. By the time he got to MSU he already had his Rip and Liz and his Cov1 amalgamated into a hybrid scheme he called "pattern matching."

[After the jump]

-----------------------------

* The Paterno-era "Hero", and "Sam" in the linked diagram were early examples of hybrid space players, and the zone-blitzing 8-man front it spawned was the basis of Rocky Long's 3-3-5 defense.

** …who discovered children were being sexually abused in his locker room and didn't tell the police because football reasons.

-----------------------------

Pattern Matching

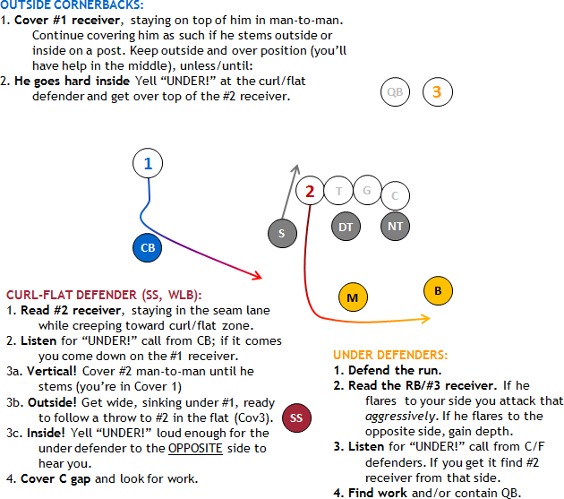

Shown here is the left side of the "Liz" variant:

------------------------

So all of this is kind of like Quarters: you're numbering receivers, and watching if they go vertical. But you're reading the receiver in front of you (in Quarters they both read the #2) and matching your coverage to what he does (hence the name). Simplified: if your guy goes vertical or angled in, you play Cover 1, if he goes hard inside or outside you play Cover 3, passing off and catching whoever enters your zone.

The thing it's most like is basketball zones, where you stay with your man until he crosses another defender, and you pass him off to that guy.

Benefits for a Modern (Spread) World

In an age when at least half of anybody's schedule is bound to be spread-to-run teams, and/or high-tempo, you need a good-for-all-seasons defensive front that doesn't take long to call and won't get torn to bits if you get stuck in that personnel.

To get the playcall in, the guys need only know if it's "Liz" or "Rip" to play relatively sound, and any time you get beyond that can be put to calling an atypical formation or a more interesting blitz. It's also a pretty balanced defense; the differences between the WLB and SAM have diminished as the SAM ends up over a slot as often as a TE.

The pattern matching looks and acts a lot like a Cover 1, except if a quarterback reads man and throws a drag, there's a guy who just got an "UNDER!" call suddenly coming down to intercept. Or if he reads Cover 3 and is attacking it with verts, there's a flat defender peeling off of that to run up the seam. And remember they can still throw a Cover 2 into the mix. A responsible quarterback could easily get frustrated trying to find spots to throw it, the more because the stuff he's used to isn't there. Quarterbacks without confidence are death to passing offense.

Special Personnel Requirements

Alabama's defense isn't much different from Penn State's back in the day, or Dick LeBeau's Pittsburgh defenses that informed both—lots of zone blitzes from shifting fronts. But more zone blitzes mean more generalized talent, since odd guys are taking on blockers or dropping into coverage more often.

To combat the spread Saban now uses hybrid space players as OLBs, and recruits safeties who can play in the box as well as range a deep zone. To give that Liz/Rip flexibility both safeties have to have Hero characteristics, and both OLBs need to be able to cover in space as well as blitz. The three down linemen have to be good at disrupting and even two-gapping to make sure the offense can't punish these lighter edge defenders—Saban tends to blow through the lives and livelihoods of a lot of DL to find a select few who can create the matchups he wants inside.

In Practice

Let's grab that first play from the 2012 Disaster in Dallas I put at the top of the article:

Michigan's throwing a deep slant off play-action, a good idea against this defense for reasons that become kind of apparent when you think about what everyone's assignments are. Alabama has a "Liz" call on:

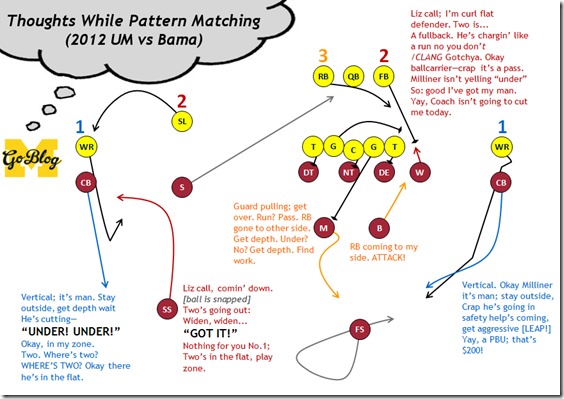

And here's what they're thinking (click for bigger so you can actually read it):

Note that this was a "Liz" call from a cover 2 look. The SAM ran in and the safety ran down right before the snap to reveal the coverage.

Despite the right read and a good throw this play was broken up by Dee Milliner, the right side cornerback, in part because Gardner's route was too skinny (he needed to cut in harder to get separation), mostly because Dee Milliner was worth way more than whatever Alabama was paying him.

I like the play design because it attacks exactly what Alabama did, or would have if Gardner's route had given Milliner an "Under" read (and Dee didn't see his curl/flat defender was tied up with the FB). The play-action off something Michigan plausibly ran (remember this was the first offensive play of 2012) forced a run reaction and made space against an excellent defense for any route in the area the WLB was supposed to cover. The bubble action to the strongside also got a guy open in the flat, which is pretty common against this defense (the SS and CB would be responsible for closing it down after a minimal gain).

How to Beat It

A few years later Urban Meyer would attack it virtually the same way: manball play-action with a spread to draw down the linebackers and commit the curl/flat defender. What made Ohio State's attack so devastating was the threat of the running game kept stressing the linebackers to react to it. This in turn stressed the cornerbacks—not Dee Milliner anymore. Ohio State did what they did to everyone who tried to play the run aggressively: test that outside man coverage with their dangerous downfield threats. They were doing so much that the defense began to expect it, and were unprepared for a wrinkle as simple as the outside receiver coming down for a crack block.

Then came the play Ohio State fans put on a t-shirt. It was remarkably similar to the run Michigan showed in play-action in 2012 (also the one play that worked for Michigan in the Spring Game), and they got the same defensive playcall: "Liz."

OSU fans labeled this "Big Ten Speed" but what beat it was old-fashioned manball overwhelming those hybrid defenders. One difference was the X receiver cracked down on the "backer", who was attacking the running back coming to his side and, because OSU had been sending that guy deep all day, was not expecting to be sideswiped. The cornerback did his job by attacking the edge and forcing the cutback.

But here's the coup de grace: notice the pulling guard got to his hole, and the Mike linebacker get erased by the X receiver's block too. That means the puller can move on to the last guy: the free safety coming up to fill from way back. Elliott would run away from defenders after, but what sprung him was a muscular attack on lighter hybrids.

Ultimately, like every defense, pattern matching is only as good as your players.