The Jug in Context

On the Halloween Day that Michigan student manager Tommy Roberts walked into a Minneapolis earthenware store, college football's power structure was in flux. Under instructions from Yost, Roberts paid 30 cents (about $9.17 today) for a 5-gallon Red Wing jug, and huffed it back to the stadium. Whether or not the dastardly Gophers were planning on spiking the Wolverines' water supply for that meeting of Western titans, they'd be thwarted.

Suspend, for a moment, all later meaning that would be attached to any programs, persons, or ceramics named above, and focus on what this vignette tells us about the game in 1903. For one, it suggests teams were capable of putting things in each others' drinking water. For another, it doesn't at all seem like Yost was confident his team, which had outscored opponents 550-0 in 1901, 644-12 in 1902, and heretofore 390-0, could simply waltz into Minnesota and win without every caution and attention paid to detail. The Jug game wasn't a friendly between old academic institutions; we were monsters and they wanted us to die.

|

| Click for big. This page is just one of the hundreds of treasures in Kenny and Jon's book. |

The Big Ten (actually Nine) in those days was colloquially "The West," with all connotations of "Wild- " intentional. This was the upstart league, and to the old guard in the East, the things the Big Nine were building on were abhorrent. Not only were lower academic standards widely tolerated for athletes, but those athletes were also given enticements like free scholarships and food, thereby undermining the authenticity of "collegiate" sports.

Travel was another point of contention: how could students be students if they were taking train rides to California over a month after the season was supposed to have ended? The modern equivalent of the 1901 team's Pasadena adventure would be Team 135 flying to India for Valentine's Day. Except if there was a good chance the players would get killed in the process: the fear of travel was justified because train accidents were common at the time. The same paper that proclaimed Minnesota's 6-6 "victory" announced that Purdue's team was in a train wreck that claimed the lives of 14 players (17 people overall).

Kenny Magee is one of those guys you will meet if you start hanging around the program. The former U-M chief of police, security consultant and magician is known on this site as the proprietor of Ann Arbor Sports Memorabilia, a sports collectible (and magic) shop under Afternoon Delight on Liberty. The store is only a fragment of the greatest Michigan memorabilia collection this side of Bentley. When they opened the Bo Museum last summer, most of it was Kenny's stuff.

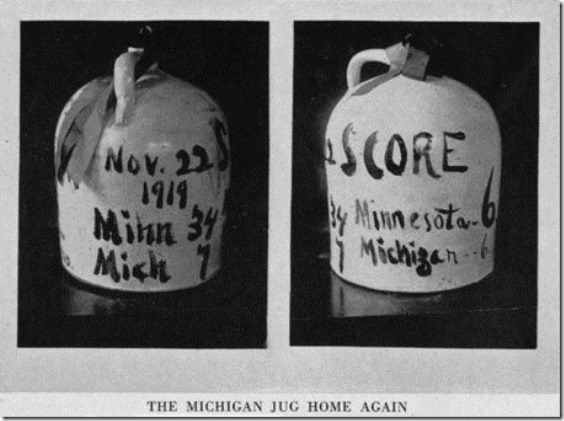

When I first met Kenny he had Eric Upchurch and me into his store for an afternoon to shoot images for the cheapest ad I ever sold for this site (resulting gif at right). A few weeks later Kenny called me and said I had to come in again and see his latest find. Now resting beneath the painting of Denard's accidental Heisman pose was an imperfect replica of the Brown Jug, apparently created by Minnesota in the '40s. Dooley (MVictors) did the primary inspection, but I got to add to the lore when I pointed out the fake had displayed the scores of the two 1926 contests incorrectly.

This find was the genesis of Kenny's foray deep into Jug lore. Dooley's comprehensive article on Jug myths, which we ran in HTTV 2013, provided the basis of what became a book on the Jug and the Michigan-Minnesota rivalry. Kenny's co-author Jon Stevens is a guy about my age who's been in and around the program in various capacities exactly that long.

Institutions tend to collect people like this. The thing is so great itself that some people will structure their lives around it. Folks invited inside will keep coming back until they're found something to do there, and they'll do that thing for a lifetime with impossible passion, and their kids will grow up knowing nothing else.

Perhaps the most devastating aftereffect of Dave Brandon's (perhaps soon to be finished) tenure here will be how many of these program people were driven away, and not accidentally. John U. Bacon is both a Michigan professor and the single most credible journalist to cover this team; first relegated to the Drew Sharp dunce seats for publishing Three and Out, Bacon has now been kicked out off the press box entirely. Bruce Madej literally invented the now ubiquitous position of sports information director; he was so effective at communicating Michigan to the fanbase that the program survived 40 years of Bo, Mo, and Lloyd's antagonism to the press without the press hating the program back. Jon Falk was the living embodiment of Michigan's institutional heritage, accessible to every player to ever need a reminder of it, but if you stand in the way of something Adidas wants to do, you can pack your trunk right now. No, that trunk stays.

The Rise and Fall of Empires

The Western Conference (Big Ten) of the early 1900s was the SEC of its day, willing to sublimate all other considerations besides winning, creating new monster programs and birthing new traditions near newly populated industrial centers by wantonly violating the artificial limitations created by the old guard to prevent it. Conversely, the Ivies (which doggedly held out for another 40 years before making their association official) were the era's Big Ten: old powers with immense institutional advantages they were actively squandering by holding out for their version of morality.

Despite the conspicuous 6-6 tie in the midst of a season of blowouts, the 1903 national championship was shared between Michigan and Princeton. You could throw a dart at an East Coast sports columnist and spill as much contempt for the Wolverines as blood, though little of the vitriol remains today. In the next 30 years Michigan and Minnesota built themselves into powerhouse programs while the Ivies drew an arbitrary moral line at considering athletic ability in admissions, and dwindled for it.

The East was still far ahead in monetization, which at the time meant packing more people into stadia. Harvard Stadium, the first modern concrete facility in college football, was in its inaugural season the day Roberts bought the Jug, and Penn began converting their wooden Franklin Field to a permanent structure that season. "The Game" (not That The Game) was affixed in 1900 as the last on the schedule by Yale and Harvard organizers who realized the rivalry could pump interest in the entire season.

Yost realized something fundamental about this sport: they'll take you as seriously as you take yourself. He made it his mission to control or at least influence anything that could touch his football program. He built a stadium expandable to 100,000 seats and his team walked the Earth as if they deserved to play in front of that many. The Yale Bowl opened to a capacity of 70,896 and Princeton's Palmer Stadium seated 45,750 when they opened in 1914, but the Midwest schools at the time were maxing out at 30,000 (Ohio Stadium was built for 72,000 but was typically half-empty).

A Book About the Jug

Kenny's book: Recommended method of purchase is to get it direct from Kenny. His shop's below Afternoon Delight, at 255 East Liberty in Ann Arbor. Or email him. Or find him at a signing, the next being at MDen this week. Also available on Amazon and kindle.

If you're from Michigan you've seen Arcadia books (Old Woodward, history of the Tigers, etc.) before at museum shops, etc. This is one of those: a few pages of backstory for each chapter, and then lots of images, many from Kenny's and Bentley's collections, and many from Minnesota's. There's the newspaper article above, and photo of Conley and his crew in '64 breaking a four-game losing streak, and lots and lots of photos of the great men who've played in this rivalry, from Bronco Nagurski to Ryan Van Bergen.

Reading it in context of this season and this era of college football, it came off like a history of the Roman Empire written in the years after Constantine. Remember when we marched into barely civilized lands, covered ourselves in glory, and shipped the treasures home? Remember when we embraced the new religion and reconstituted as an Eastern-focused superpower? Remember when we didn't spend as much time talking about how awesome Rome was because we were so engaged in making it so?

Now it's Tuesday before a Jug game with as much meaning to the national landscape as a Harvard-Princeton matchup in 1964. The Michigan Stadium I'll visit is itself a highly leveraged brand; the teams facing each other will both operate on dogmatic principles long since cast wayside by programs far more willing to push the established lines of righteousness, be they managing the gameclock or ignoring NCAA's unenforced Title IX rules and outdated ideals of athletes as "just students." And here I am, slowly becoming one of those people whose life is defined by attachment to an institution that revels in its history while missing the most important lesson from it.

Which is…

Strip off the paint and the scores and the logos and what you have is a clay jug we bought because Yost would burn in hell rather than let an advantage slip by. Fielding wouldn't pass muster at a lineup of "Michigan Men." He was an epic asshole who stood out in a period when assholes were highly tolerated. It's important to me that Michigan stands for more than that. But if Michigan and the Big Ten are to avoid the fate of the Ivy League, they'll have to operate on the same principle that every successful program ever has: First, you win.