Takeaway: offenses were so potent by the 1950s that teams would punt on normal downs to gain field position, and the opponent wouldn’t have a guy ready for this.

Michigan’s outmoded punt formation is a horse we’ve been beating since Hoke’s first year despite it being about as dead as, well, NFL-style punt formations in college football. In light of last week’s punt-o-rama first half I got a question from a reader asking if we’d actually explain what the difference is between them and why one is better than the other.

So yeah, let’s do that, with the foreknowledge that Hoke isn’t going to change no matter what we say or prove; this is so you’ll know what you’re seeing only.

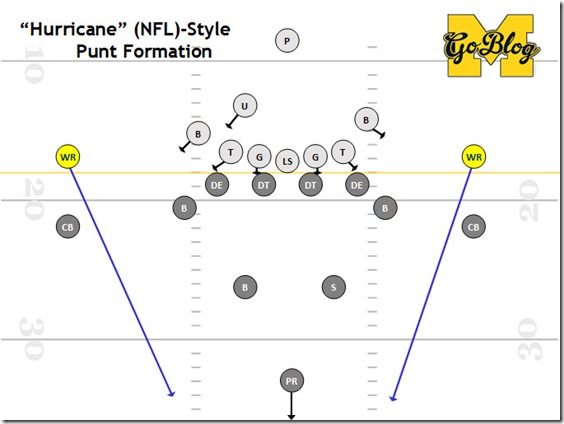

Here’s the punt formation that Michigan uses:

Like all things in football there’s a hundred different names and minor variations on it but the gist has remained the same since a time before the word “pattern” was replaced with “formation.” It follows the same rules as normal downs: seven men on the line of scrimmage, four in the backfield, with the backs plus ends on the line counted as eligible receivers. Since the snapper has to concentrate on that he typically doesn’t figure into the punt protection scheme except as a bonus dude to get in the way or cover a lane. The O-line does the front-line blocking, with a couple of wingbacks to protect against an edge rush and an up-back on the “leg” (…of the punter) side to catch anything that comes through, like an RB in pass pro, reading inside-out.

This protection scheme has worked for two generations and remains pretty safe from all kinds of punt blocking attacks unless a block is blown. It packs guys in the middle and on the outside the blockers mostly just have to keep rushers from getting inside before the punt is off. The two “ends” (wide receivers, really) are gunners, releasing downfield on the snap to attack the returner before the ball arrives and he can set up his blocking.

The NFL still uses this formation because they have to:

During a kick from scrimmage, only the end men, as eligible receivers on the line of scrimmage at the time of the snap, are permitted to go beyond the line before the ball is kicked.

Exception: An eligible receiver who, at the snap, is aligned or in motion behind the line and more than one yard outside the end man on his side of the line, clearly making him the outside receiver, replaces that end man as the player eligible to go downfield after the snap. All other members of the kicking team must remain at the line of scrimmage until the ball has been kicked.

Translation: only the two outside guys can be gunners; everyone else on the punting team can’t release downfield until ball leaves foot. This was an attempt to cut down on injuries, figuring it’s best to keep as many collisions between high-speed NFL bodies to short range meetings in the backfield.

[After the jump: niche opportunity leads to adaptation]

College football doesn’t have this rule, and that’s why a different punt strategy could evolve:

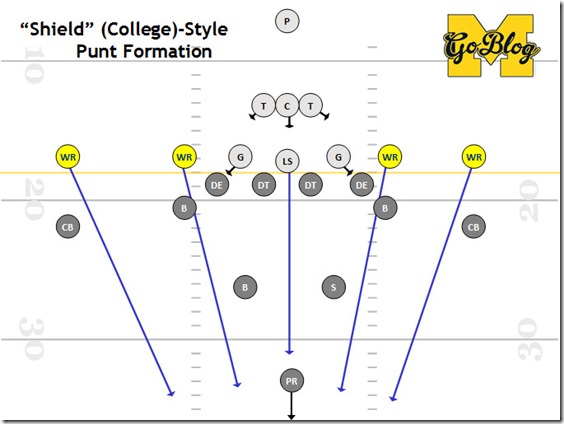

The two most common names for this style are instructive. It’s “spread” because you wind up with guards lined two yards away from the snapper, and four “receivers” (ie gunners) instead of two. It’s “shield” because the key to it is setting up 900+ pounds of meat shield about five yards in the backfield, behind whom the punter can do his thing. From a personnel standpoint you are basically trading three fullbackian guys for two WR/DBs and an extra OL.

Why only college? Without the NFL’s two-gunner rule college teams are free to send as many dudes as they like toward the punt returner right on the snap. The only thing holding them back is having to block long enough to get the punt off safely against all fronts. So: how do you get more guys released? They tried various rugby-style things in the ‘90s, but the real winner was going to a defense-in-depth strategy that required two (!) fewer blockers to get the same (actually better) rate of preventing blocks. The only tradeoff is less opportunity to pull a fake pass; that happens so rarely it’s not much of a loss. In the pros, since you can’t send covered ends downfield anyway, might as well stay in a normal-ish offensive formation.

The key difference is how they block the A-gaps (the spaces between the center and the guards). In a shield punt the A gaps aren’t defended at the line of scrimmage. Rather you have three very large men—who can thus absorb a rusher without giving ground—standing about five yards back. They act like a gate: they line up with a space for the ball to be snapped, then close ranks. Those three guys are responsible for catching any defender that comes through the A gap, and keeping whatever else leaks through too far outside for them to get to the punter.

Provided they do their job—more of which than any coach would care to admit being to stand in the way and be large—there should be a nice 7-yard cushion behind them for the punter to step into and get the ball off. Provided the shield isn’t shoved backwards, in the time it takes for the defenders to engage then break through or around them, the punt will get off.

With the eye of the storm kept clear by that mechanic, the rest of the blocks are quick and need only widen the vectors of the non-middle attackers. The guards’ jobs in particular are to get inside the ends and shove them a yard horizontally; then they too can release downfield to join the punt coverage. The punter receives the ball about 12 yards behind the line of scrimmage, and those seven yards in front of him are his safety zone to step into; the punt release point is right behind the shield.

The only way to beat it is to swarm the shield. If you can’t figure out why this scheme scares coaches, look again at the five people on the line of scrimmage: there’s extra WRs on the line instead of offensive tackles. Until they could see it working at other schools, many a coach probably got to the point where you say “don’t block the DTs at the line” and walked out of the meeting.

Even if you told him a punt is your highest yardage offensive play.

If the defense packs more guys onto the line, you close up and put a hat on a hat, still leaving the three most dangerous attackers for the shield. If they have four attackers in the A gaps, the guard to that side will change his technique, blocking down on an inside guy to delay anything behind that block (the shield takes care of the DE). The result is twice as many gunners heading downfield at the snap to cover the punt.

To date defenses have yet to find a method of consistently getting pressure, even on an all-out 10-man attack, unless the blocking is screwed up or the punter doesn’t get the ball off in time.

Faking is a bit harder to do because you technically have two tackles (the covered inside WRs) downfield. NCAA refs let that go to extraordinary lengths when it’s lumbering dudes wearing numbers in the 70s; not so much when it’s a guy wearing 85 running downfield like it’s four verts. You’ll note when Michigan was a shield punting team we had the punter just run it.

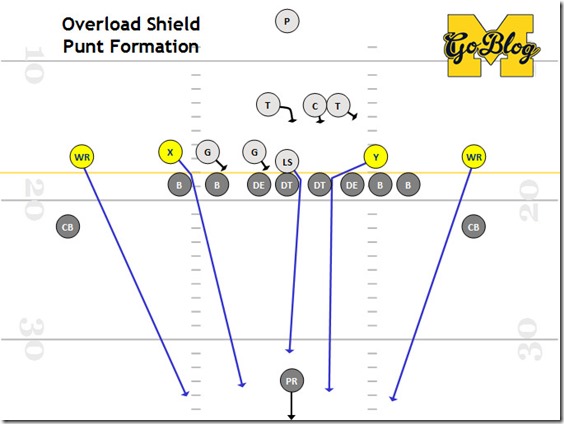

There are variations. One tinker gaining popularity is to run it from an unbalanced line, blocking hat-for-hat on the side you’re punting to and saving the shield for the backside.

That’s an overload formation by the way, but it’s a good example of how the shield punt’s rules translate to the defense trying to get pressure:

The Y receiver just has to run across the formation and bang the DT to interrupt that whole side; four guys do get into the three-man shield, but the unblocked dude is the furthest out and therefore can’t cover the horizontal difference before the punt’s away. On the frontside, everybody blocked down—so long as they got a hat across the defender there’s no way that guy’s getting upfield fast enough to cover the punt.

How do you know it’s so effective?

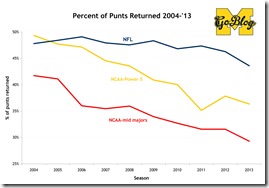

Data (click bigs):

Nothing else—no rule change or game mechanic—has changed punting in this period except the spread of spread. Mathlete’s looked at it before too. The above were from data grabbed at ESPN. See trends? The likelihood that a punt will be returned has dropped 30%. Those that do get returned are getting 15% fewer yards. I split out the Power 5, since they’re generally working from the same pool of punters as the NFL, and watched the rate of their punt returns drop from the NFL normal to less often than the mid-majors, with their non-power legs, used to get.

Because it can protect the punter so successfully, and moreso because it can get so many tacklers downfield before the blocking, the spread punt has made successful punt returns a rare thing. We saw a case example of the spread punt’s efficacy last week in Ann Arbor. Miami (not That Miami) managed to get what seemed like the same value from their punts as Michigan despite their punter’s leg having a range that didn’t even get to Norfleet. Last week Michigan missed an opportunity on a muffed punt against ND precisely because they only had one guy downfield to challenge for it.

So why doesn’t Michigan do this? The best reason I’ve been able to come up with is maybe they don’t want to put any more on their offensive linemen right now? That is a bad reason; teams that have transitioned to the spread punt did so in a few practices and were effective at it. The real reason is probably that they want to be Alabama, i.e a pro team in college uniforms. Punt blocking isn’t all that hard; you just need to get in the way of interior rushers and delay the outside dudes. The biggest way to screw it up, from a coaching perspective, is to be the last program on the continent to adapt to a superior method.