Alternative Title: O’Bannon… You Came And You Sued For Injunction…

Alternative Alternative Title: Selling Little Bottles of OLB #9

The O’Bannon antitrust trial started this week, and because trials are fun and listening to the NCAA’s lawyers is amusing as hell, let’s talk about it. To properly understand this, we have to go back to the year 1890 and the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act…

Sweet tapdancing hell we are NOT doing this again. We’re not going back to freeking nineteenth century.

Oh come on, this stuff is interesting.

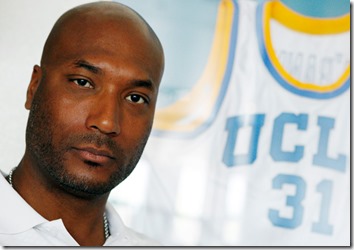

|

| Plaintiff's attorney |

I just died of boredom.

Fine. But we at least have to go back to the year 1995. Ed O’Bannon is the best player in college basketball; he averages 20.4 points and 8.3 boards and wins the Wooden award, and his UCLA Bruins win the national title. So that was cool. Then, a decade later, a younger relative showed O’Bannon a copy of EA Sports’ NCAA 2007, which contained some classic teams, including the 1994-95 UCLA Bruins. O’Bannon noticed that (a) he was in that game, and (b) he hadn’t been paid anything for his appearance in the game. This, he deduced, was crap.

But he waived his rights to get paid for that, right?

Indeed. All athletes, before they play a single second, have to sign a waiver that relinquishes any rights they have in their likeness. The NCAA can use any player’s image for whatever the NCAA sees fit, and owes the athlete nothing. In fact, as you may know, if players DO get paid for their likenesses during their playing careers, they get suspended for an entire season. No, wait, that’s pot. You get suspended for one half of one game. But still, athletes can’t get paid.

There is, however, a way to get around that waiver. If the NCAA violated the law in forcing O’Bannon and other athletes to waive those rights, the waiver are invalid. If only such a law was passed during the Harrison Administration (NNTHA) that Bolded Disembodied Alter-Ego would let me discuss…

Sigh. Fine, just make it quick.

|

| Other plaintiff's attorney |

WOO. The Sherman Antitrust Act makes certain anticompetitive behaviors by entities that have dominant positions in a given market illegal. It’s not against the law to create a monopoly, but if you have one, you can’t use it to restrain trade or hurt consumers. If you’re Microsoft, you can install Windows on 80% of all computers, and that’s not a problem. If you use that 80% market share to bundle everything with Internet Explorer so people won’t use Netscape Navigator, that IS a problem.

Yes, the problems of the 1990s were bizarre in hindsight.

And what exactly are the plaintiffs whining about?

When athletes start playing, they have to sign a waiver that surrenders all of their name, image, and likeness (“NIL”) rights to the NCAA. The NCAA can then use those rights however they see fit without compensating the athletes in any way. Two ways they use athletes’ NIL rights are in licensing for video games and licensing for live television broadcasts of games, promos, etc.

For video games, it’s a pretty easy case to make. The NCAA used to grant EA Sports the right to develop and sell video games with all of the FBS teams and players, and in exchange EA Sports would add a little depth to the Scrooge McDuck coin vault swimming pool. The NCAA has tried, half-heartedly, to argue that it is a coincidence that the rosters of every college team have every player with the appropriate height, weight, position, number, skin color, athletic characteristics, and general appearance. This issue bleeds over into other not-about-Player-X-but-definitely-about-Player-X stuff like jersey sales; sure, Michigan wasn’t selling Denard jerseys. But they were selling Denard jerseys.

The other issue is television rights. Right now, conferences sign television deals with networks, networks televise games, networks pay conferences large sums of money, conferences distribute that money among the member schools, and member schools give players… uh… the satisfaction of a job well done. O’Bannon is arguing that part of the value of those broadcasts are the result of the NIL rights that the players have to sign over to the NCAA.

[AFTER THE JUMP: More of what we're talking about here]

Whoa whoa whoa… do networks actually have to have athletes’ permission to broadcast them?

|

| He thinks he's entitled. |

I have no idea, and neither does anyone else. It’s still an open question, and one of the biggest open questions of the whole trial. Are the networks broadcasting the teams or the players? Or both? Athletes don’t generally give explicit permission to broadcast them playing, but, in pro sports those rights are presumably part of collective bargaining agreements with the respective professional league. The fine print on the back of most tickets clarifies that the spectator is granting the use of their NIL rights in broadcasts, but the band doesn’t. It’s an interesting question, and will be a hot topic in the trial.

FWIW, the NCAA has argued that they don’t sell the rights to the broadcast; they simply sell the right to access the premises. Seriously. They argue that ESPN pays the SEC a gajillion dollars for the right to put cameras in the building. The ‘broadcasting football and running ads’ thing is just a nice little bonus.

So, how much is O’Bannon looking to get paid?

O’Bannon isn’t looking for money, at least not directly. Instead, he’s looking for an injunction, which is the legal version of a rolled-up newspaper to the nose of a disobedient dog demanding that they stop certain behavior. There was a related suit that was asking for damages filed by former Nebraska quarterback Sam Keller, which was temporarily combined with the O’Bannon suit. But the judge in the case (Claudia Wilken, U.S. District Court for Northern California) separated the two cases for the trial phase.

O’Bannon originally filed his action against EA Sports and the Collegiate Licensing Company* as well as the NCAA. But EA Sports and the CLC settled with the plaintiffs for $40M to settle Keller’s claims, and agreed to stop producing NCAA Football and Basketball games to satisfy O’Bannon’s demands. Then, on Monday, literally moments before the O’Bannon trial, the NCAA then settled the Keller suit for $20M. So the only remaining part of the suit is the injunction against the NCAA.

*The CLC is a trademark licensing and marketing company that operates as the licensing arm of the NCAA, many conferences, and most major schools including Michigan. Look at the tag on any piece of ‘officially licensed’ college stuff you have. See that little red, white and blue circular logo? That’s them.

Wait, why did they settle the Keller suit, but not this?

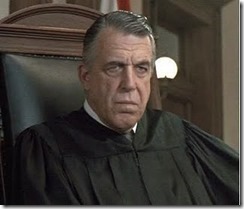

|

| Judge Claudia Wilken |

Best guess: the NCAA has lots of money. They can throw money at problems to make them go away. But settling a suit for injunctive relief usually means you have to DO something. They’d have to change the status quo on licensing, which they might see as unleashing a change they can’t control or survive.

And this whole thing is about video games and broadcast rights?

Yes and no. Those are the complaints, but the broader issue is that the judge is looking at whether the NCAA is acting in violation of antitrust laws with its current system of restrictions. If it is, she can craft an injunction that addresses the extent of the violation. That remedy might be “hey, no more video games without athlete permission” or “no more NIL waivers” or “you have to give the players a cut of the TV money” or “athletes can’t be prevented from profiting from their own likenesses” or “the amateurism rules no longer apply” or “the entire NCAA rulebook is now gone.” And even if the injunction is more limited (which would be my guess), it would open the door to similar future claims. For the NCAA, winter is coming.

Yeah, yeah, Game of Thrones is awesome blah blah. Who has to prove what?

O’Bannon’s lawyers have to show that the NCAA engaged in an agreement, contract or conspiracy to manipulate prices, the agreement unreasonably restrained trade, and that the restraint affected interstate commerce. Don’t worry about the last point; it’s just a thing that allows the feds to get into it. No one will contest that part. The first point is probably a given, too; one of the NCAA’s primary purposes is to make sure all schools provide the same level of benefit (which is below what some might receive in the open market). The phrase "impermissible benefit" exists for a reason, after all.

The big issue, then, is whether the NCAA unreasonably restrains trade. The plaintiff has to show that the NCAA uses its monopolistic control to harm/manipulate/damage some discernable market. And they can get away with pretty much anything if they have a good enough reason.

The plaintiffs are arguing that the way the NCAA handles its business harms two markets: the college education market and the group licensing market. In other words, if the NCAA wasn’t such a buzzkill, the market for college athletes would be different and more beneficial to the athletes, and there would be a value for athletes to use their NIL rights that they are currently prevented from receiving.

The college market argument is a pretty easy one. If the NCAA allowed it, would players be paid more than they currently are? Well, yeah. Because some players (looking at you, Ole Miss and Clemson) are already getting paid more than the NCAA allows. The NIL argument isn’t much harder, because they already have the head of EA sports saying they would have been willing to pay more to be able to use actual names in the games rather than QB #16.

So, victory?

|

| NCAA attorney in action |

Not yet. The NCAA can argue that without those restrictions, the nature of college sports would be so different that the rules are reasonable. The NCAA has several arguments that, sure they’re restricting the market, but it’s FOR the market. Their arguments are as follows:

- Amateurismis good. Specifically, the game wouldn’t be the same if the players weren’t amateurs. No one would care. They would be all, “eh, these guys get paid,” and turn to… uh… whatever else is on TV on fall Saturdays. This argument is a really hard sell, because (a) players ALREADY get paid (how many times have you heard an anti-player-pay guy scream “THEY ALREADY GET FREE TUITION THAT’S LIKE A BILLION DOLLARS AND I HAD TO SELL MY UNCLE'S NEPHEW TO PAY FOR COLLEGE”), and (b) the NCAA is already talking openly about an additional stipend on top of the normal scholarship amount. Besides, as the plaintiffs pointed out, there are less restrictive means of ensuring that the players are “amateurs” during their playing career, like establishing a fund that pays players after they leave school.

- Limits are necessary for competitive balance. If everyone gets paid for their likenesses based on unfettered market forces, people are going to get a bunch more money at Alabama than they are at Eastern Michigan, and they’ll make more at Eastern Michigan than they’ll make at Northwest Bumblemuffin State. This will necessarily cause all of the most talented athletes to go to the biggest name schools and conferences. Which is totally not what happens now. All schools recruit the same athletes with the same level of success. (In a related argument, the NCAA will argue that some schools will be forced to leave Division 1 because they can’t afford to keep up with the Sabans.)

- We ain’t come to play SCHOOL. The NCAA is arguing that without the amateurness of college sports, the connection between the student and the athlete in “student-athlete” would be lost. Judge Wilkin has said that for this article to succeed, the NCAA must show that it “actually contributes to the integration of education and athletics.” I can’t honestly think of a single good argument for this one. I can’t even pretend to defend it before shredding it. Sorry.

Okay, then how’s the trial going so far

Ed O’Bannon’s testimony highlighted day one, though his testimony will probably be the least consequential. O’Bannon testified about the time balance between being a student and an athlete, about being encouraged to take easier classes and less challenging majors, and the about signing the waiver of naming rights. The NCAA spent a lot of time trying to get O’Bannon to talk about all the benefits he got from playing, and how John Wooden was a great mentor. Which is nice… and totally irrelevant to the actual issues of the case. Easily the best moment in O’Bannon’s testimony, though, was when the NCAA’s attorney trying to get on the record that Bill Walton doesn’t think players should be paid. Because, as you can imagine, having Bill Walton on your side is checkmate in ANY TRIAL.

The more important testimony was that of Stanford economics professor Roger Noll, whose testimony lasted for a total of 11 hours over three days. Noll (presumably in a Ben Stein-esque rhythm and cadence) explained the basic microeconomic theory behind the plaintiff’s case; that without the restraints put in place by the NCAA, players would receive more money, both in terms of compensation from schools and in licensing of their names, images, and likenesses. He also explained how the NCAA is a cartel, in that the various member organizations formed a joint association that sets a series of rules for how they operate in the market.*

Noll also testified about the ancillary effects of the NCAA’s restrictions. He argued that the money that would otherwise go to athletes is being used on things like coaches salaries and construction projects. These “inefficient replacements,” according to Noll, demonstrate the excess money that are being used as replacement enticements and signals of a strong program for recruits.

Tyrone Prothro, he of the AAAARRRRGGGG DON’T SHOW THAT REPLAY, testified on day three. He shared the story of how his miraculous catch helped win Alabama a $100,000 prize, and the NCAA used it in ad campaign and several other ways, but when Prothro wanted a copy of the picture the school told him he would have to pay for it. He also testified about the lack of integration of the athletes with the normal students, and how the NCAA has told him they won’t pay for future surgeries on his astoundingly shattered leg.

Day four was a battle of the television execs. Former NBA TV executive Ed Desser testified for the plaintiff that television deals assume that the teams/conferences/whatever are transferring the rights to broadcast the players; that the NIL rights are “at the heart of what's being conveyed" by the conferences. NCAA witness (and former CBS President) Neal Pilson, testified that networks broadcast teams, not players. He also pointed out that many agreements don’t explicitly mention participant NIL rights. He also wandered into the “people wouldn’t watch players if they were paid” territory, which was odd and somewhat outside his wheelhouse.

*One fun tidbit is that the NCAA’s economic expert also referred to the NCAA as a cartel. In a textbook he wrote. The best expert the NCAA could find for their cause literally called the NCAA a textbook example of a cartel.